FAKE: Confronting hatred: 1 Kenyan, 1 American working together

Colin Stewart is a 45-year journalism veteran living in Southern…

THIS ARTICLE WAS BASED ON DOCUMENTS THAT, ON INVESTIGATION, APPEAR TO HAVE BEEN FAKED. It has been labeled “FAKE” rather than simply removed from the blog. As a result, any readers who follow links to it will see the “FAKE” label rather than merely receiving an “Oops! That page can’t be found” error message.

— Colin Stewart, editor/publisher of this blog

This is the third of several articles about Kenyan LGBTI activist/journalist Joseph Odero, targeted for assassination for his work on behalf of murdered LGBTI teenager Muhadh Ishmael. Despite a nearly fatal attack in January, Odero testified in court about what the murdered youth told him, and now he needs a kidney transplant to survive.

To help pay for that operation, donate to the Joe Odero Fund. Because Odero remains at risk from further attacks, his current location is undisclosed and protective pseudonyms are used throughout this article.

Confronting hatred:

1 Kenyan, 1 American working together

After Ishmael’s murder, Joe felt compelled to seek justice for him.

Justice and a decent burial.

As a reporter and LGBTI rights activist, Joe Odero had covered the story of Ishmael, an intersex teenager in Kenya who was fatally mutilated by his family for not behaving as they demanded. But Joe wasn’t satisfied, even after the story was published.

Ten thousand miles away in California, his editor, Colin Stewart, had a different response to the publication of Ishmael’s tragedy. As a veteran journalist, he considered Ishmael’s story to be a riveting tale with an unhappy ending. But it was a story that had been reported, written and published on Dec. 23, 2015. The time had come to move on.

Please, no, Joe pleaded. He wanted justice to be done. He urged Colin to organize a fund drive to raise money to pay for Ishmael’s burial. To have access to the body, Joe would have to pay Ishmael’s hospital bill and the per-diem charges from the morgue. Joe also wanted a post-mortem. And for that he would need to make another bus-and-taxi trip across Kenya from his home near the Ugandan border to Malindi, where he would need to organize activities.

Such trips were routine for Joe. In his work as a peer counselor and HIV educator, he had often traveled around Kenya.

Sometimes he would be paid 2,000-3,000 Kenyan shillings ($20-$30) for transportation to locations where he would do volunteer work for local non-profit organizations such as Kisumu Initiative for Positive Empowerment and Changing Attitude Kenya, which lobbies for the Anglican Church of Kenya to accept LGBTI people on equal terms with every other Christian. At times he might be paid 6,000 Ksh ($60) for a month’s work as a peer counselor, discussing issues of sexuality and human rights with LGBT Kenyans or health-care strategies with HIV-positive Kenyans.

Joe had done that work since 2013, the year when he was expelled from Egerton University for LGBTI rights advocacy.

Now he wanted to be an advocate for a dead intersex Muslim.

For Colin, that idea wasn’t out of line. After an American journalism career at medium-sized daily and small weekly newspapers in Massachusetts and California, Colin had retired at the end of 2011. Inspired by the work of a gay friend who is an Episcopal priest, Colin launched the Erasing 76 Crimes blog to focus on the struggle for fair treatment of LGBTI people in 76-plus countries with laws against same-sex intimacy.

For Colin, the blog was a way of putting his experience to work while also living out the Christian command to love one’s neighbor.

In that context, Colin was easily persuaded by Joe’s impassioned plea to help seek justice for a dead intersex Muslim, especially in one of the 76-plus countries where a combination of homophobia and a punitive anti-homosexuality law provided the backdrop for the violence that took the teenager’s life.

Joe had become an activist because of his experiences of being stigmatized in Kenya’s homophobic society. He’s a religious person, but his activism grew out of his life as a gay Kenyan rather than from his faith.

Colin agreed to Joe’s request. Thinking that an appeal before Christmas might be more successful than one that appeared later, Colin quickly organized a fund drive. The blog’s announcement of the appeal appeared on Dec. 24, 2015, with the headline “Will Kenyan intersex victim get a decent funeral at least?”

Readers’ response was modest but international. A total of US $419 was donated via PayPal by well-wishers in the United States, Canada, France, the United Kingdom and Australia. That total was less than the $540 needed, but Colin made up the difference and sent it to Joe.

On Dec. 30, Joe took the bus and taxi back to Malindi, where he paid the hospital and the morgue. He arranged for the post mortem on Ishmael’s corpse and for his funeral, taking on the role of next-of-kin in the post-mortem paperwork and on the burial permit.

While a pathologist conducted the post mortem, not everyone in the examination room was sympathetic to Ishmael.

“Children born with abnormal genitals should not be left to grow,” one nurse exclaimed. “It’s advisable always to kill them while young.”

Another nurse said during the post mortem that intersex people and other sexual minorities “encourage men to behave as women, and women to behave as men. They deserve death or a long jail term.” Joe kept silent and did not challenge her ignorant homophobia.

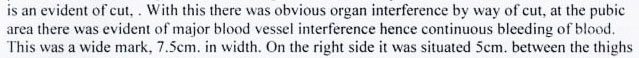

Joe received the post-mortem report on Dec. 31. It stated that the examination of Ishmael revealed “a fresh red wound” and “continuous bleeding” in the pubic area. The cause of death was “excessive bleeding and irreparable tissue injury.”

With that document in hand, Joe went to the police station and reported the crime. Some police officers sneered. One of the senior police officers said, “The devil deserves to join the devils.” And in Swahili, “Hao mashoga wafe kabisa,” which means “Those gays deserve to die.”)

But other police officers took Joe seriously. He signed a witness statement about what Ishmael had told him. Before the police would accept it, he had to provide his contact information. Joe wrote down his name, his telephone number and his city — Kisumu. He knew that if the case went to trial, the witness statement and contact information would be provided to the defense. But he did not know that keeping his location secure would become a matter of life or death.

After leaving the police station, Joe hired a grave-digger and arranged for a pickup truck to transport Ishmael’s body to the cemetery. At the burial, the only people present were Joe, the grave digger and three members of the local LGBTI community. Because Ishmael was a Muslim, Joe wanted the burial to be conducted in accord with Muslim traditions. That was accomplished with guidance from the only two Muslims there — the grave digger and one of the LGBTI mourners. The ceremony consisted of prayers for Ishmael, recited by the grave-digger.

After the burial, Joe left Malindi and headed home to Kisumu, his mission complete.

He was ready for a rest, but that’s not what he found.

What awaited him at home were death threats and a murder squad.

To be continued …

Donate to the Joe Odero Fund

Also see the series overview: “Confronting hatred: the Joseph Odero story.”

Dear Colin,

I am sorry that you were takin in by this man. I heard conflicting stories about him after I put together a website for him. I have now taken down that website and severed all connection with him.

Regards,

Stephen

Thank you for your sympathies, Stephen. I’m glad that you took down that website. I hope that other people will be spared from his fakery.

— Colin