Here’s why activists need international help vs. Barbados

Colin Stewart is a 45-year journalism veteran living in Southern…

Three LGBTQ Barbadians have filed a petition challenging laws in Barbados that outlaw “buggery” and other intimacy between consenting partners, including partners of the same-sex. Here is an explanation of what’s going on, in Q & A format.

This is the explanation from the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, which is one of the sponsors of the petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR):.

International challenge to Barbadian laws criminalising LGBTQ people: Questions & Answers

Three Barbadians — a trans woman, a lesbian and a gay man — have filed a petition against Barbados before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) challenging laws criminalising “buggery” and other intimacy between consenting partners, including partners of the same-sex, as violating numerous rights guaranteed in the American Convention on Human Rights. This backgrounder answers some key questions related to this petition.

1. Which laws are being challenged?

The petitioners are challenging two sections of the Sexual Offences Act (SOA) of Barbados.

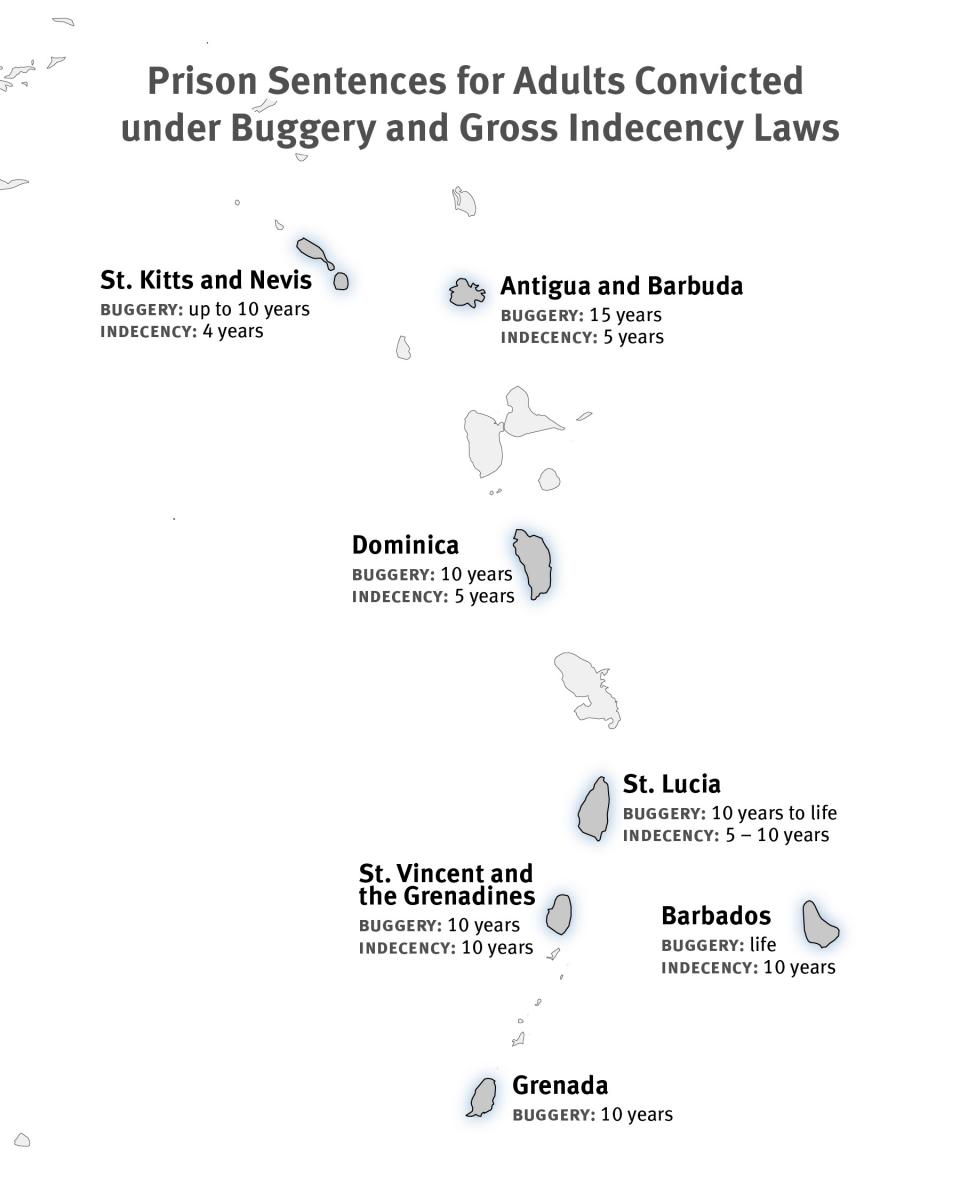

- Section 9 criminalises “buggery” — which the courts have confirmed means anal sex — between men, but also between a man and a woman. The maximum penalty is life in prison.

- Section 12 criminalises “serious indecency,” which is sweepingly defined in the SOA as any act by anyone “involving the use of the genital organs for the purpose of arousing or gratifying sexual desire.” The maximum penalty is 10 years in prison if the act is committed on or towards a person aged 16 or older; the penalty is higher in the case of person under the age of 16.

The prohibition on buggery was first enacted in 1868, when Barbados was under British colonial rule. Although Barbados achieved independence in 1966, it has preserved this offence in Barbadian criminal law. The prohibition on serious indecency was first enacted in 1978, but its roots also lie in colonial-era English law.

2. Why are these laws being challenged?

These laws violate multiple fundamental rights of all people in Barbados. For example, by criminalising a wide array of consensual sexual conduct between adults, they violate the right to privacy of all sexually active people.

In addition, while these laws appear to be neutral regarding sexual orientation, de facto they also both embody and encourage discrimination particularly against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) people, in various ways.

- The law against “buggery” inherently criminalises sex between men and is widely understood as existing for this purpose, even if it is settled in Barbadian law that it can also encompass anal sex between heterosexuals. Gay men and (some) trans women are directly criminalised by the buggery law.

- The offence of “serious indecency” is extremely broad; on its face, it captures any consensual sexual activity by anyone that involves the genitals. Of course, it is the sexuality and sexual activity of LGBTQ people that is more far commonly considered to be indecent because it differs from dominant norms. The heterosexual conduct theoretically covered by the law is generally not perceived the same way and therefore not likely to be considered criminal. Even when seemingly neutral, there is a long history of indecency laws being used to target same-sex intimacy.

- Because the buggery law turns gay men and (some) trans women into presumed criminals, and the indecency law extends the taint of potential criminality to all LGBTQ people, these sections of the SOA send a powerful message that people — whether state agents such as the police or private individuals — are entitled to discriminate and commit other human rights abuses against LGBTQ people (and those perceived to be LGBTQ).

- Because the “serious indecency” law contributes to and reinforces a more general tigma against homosexuality, it encourages discrimination and violence against women who are, or are perceived to be, lesbian.

- Sexual orientation and gender identity are different facets of a person. Yet they are often incorrectly conflated and equated because they both involve difference from presumed, accepted norms — of sexual conduct and/or of the gender ascribed to a person at birth. When a person’s gender presentation is perceived as differing from the gender norms associated with the genitalia or other physical sex characteristics they have (or are assumed to have), it is not uncommon for others to assume that their sexual activity is also “deviant” — possibly criminally indecent, including possibly buggery — even if this isn’t the case. As such, the criminalisation of consensual same-sex sexual activity also contributes to discrimination and violence against people who are identified as transgender.

The SOA provisions criminalising consensual sexual activity not only invade privacy, and have a particularly discriminatory effect on LGBTQ people, they also undermine the right to health. They create a hostile climate for LGBTQ Barbadians who seek any kind of health services, particularly sexual health services. Among other things, such laws, and the stigma and discrimination they contribute to, deter trans people, gay men and other men who have sex with men (MSM) from seeking critical HIV services, including testing, treatment, care and support services. This undermines an effective national response to the epidemic. Changing these laws is a human rights and public health imperative.

3. Why are these petitioners bringing this case?

Two of the petitioners in the case are directly at risk of criminal prosecution for “buggery” as a result of the expression of their sexuality with consenting partners. The third could conceivably be at risk for “serious indecency” charges.

Petitioner Alexa Hoffmann, the only petitioner willing to be publicly identified, is a heterosexual trans woman (although her female identity is not recognised in law and she is therefore still treated legally as a man). Petitioner “D.H.” is a gay (cisgender) man. In each of their cases, their sexual activity with male partners includes anal sex — “buggery,” prohibited by SOA section 9. Both Hoffmann and “D.H.” could be incarcerated for life for private sexual intercourse with consenting adult same-sex partners. Finally, petitioner “S.A.” is a lesbian; she and her adult female partner could be subject to prosecution and imprisonment for “serious indecency” for their consensual acts of intimacy.

Beyond the risk of criminal sanction, all three petitioners have experienced discrimination, harassment, threats on multiple occasions, and even homophobic/transphobic attacks — abuse and hostility that is encouraged by these SOA provisions. In cases of physical violence, too often Barbadian police fail to adequately assist and protect, at times ignoring or failing to effectively investigate attacks against LGBTQ people. For example, most recently, the petitioner Alexa Hoffmann, a well-known trans activist, was savagely attacked with a meat cleaver, yet the police allowed her attacker, who had been identified and was easy to locate, to remain free for two days. One officer told Hoffmann, on the condition of anonymity, that the police are reluctant to assist with cases involving LGBTQ people.

In light of their clear or potential legal jeopardy under the SOA provisions, and their experience of other human rights abuses in a climate of anti-LGBTQ hostility created in part by the SOA provisions, all three petitioners have filed a petition before the IACHR asking for a review of Barbados’s laws effectively criminalising the sexuality and gender identity of LGBTQ people as breaching various rights under the American Convention on Human Rights (the Convention).

4. How do these laws violate the American Convention on Human Rights?

The two SOA provisions that are being challenged violate numerous rights guaranteed by the Convention. Barbados ratified the Convention in 1981, which means it is legally bound to respect this treaty. By unreasonably and arbitrarily criminalising the private intimate acts of consenting partners, and by inviting and inciting violence and discrimination against LGBTQ people or people perceived to be LGBTQ, the laws violate, both directly and indirectly, the rights of Barbadians to the following:

- privacy;

- non-discrimination and equal protection;

- freedom of expression;

- physical, mental and moral integrity;

- family; and

- judicial protection.

Barbados has recognised these human rights in international human rights treaties it has ratified, and most of them in its own Constitution. The infringement of these rights is indefensible in a free and democratic society.

5. How do these laws fuel the HIV epidemic in Barbados?

As has been widely and repeatedly recognised, including by such bodies as UNAIDS, the UN Development Programme (UNDP), the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the Global Commission on HIV and the Law, a legal environment that directly or indirectly criminalises and stigmatises LGBTQ people undermines effective responses to HIV.

Such laws create apprehension among LGBTQ people, who fear that even the mundane activities of daily life will lead to accusations of criminal acts or provoke discriminatory or abusive treatment. For example, a man seeking HIV testing or visiting the doctor for a check-up who indicates he is sexually active with a male partner or partners is confessing to a crime. More generally, open and non-judgmental discussion about sex between persons of the same sex, including safer sex education for purposes of HIV prevention, is more difficult in a climate where anal sex or other acts of intimacy between same-sex couples is a crime, and anyone identified as an LGBTQ person risks discrimination, violence or possible prosecution.

Furthermore, the government does not wish to be seen as “promoting homosexuality” or providing “special” services to a criminalised population. This complicates and undermines HIV-related programs (outreach, testing, support, treatment, care) by government agencies that target men who have sex with men (MSM). The result is the creation of significant barriers to effective HIV and AIDS health programs. Partly as a result of this environment, Barbados is in the midst of an ongoing HIV crisis: about 14% of all MSM are living with HIV, according to most recent estimates from UNAIDS (in 2017).

6. Why is a legal challenge necessary?

For many years, evidence has been mounting of the harms caused to Barbadians by criminalising LGBTQ people, including the stigma, discrimination and violence encouraged by such laws. The continued criminalisation of consensual sex by LGBTQ people through the “buggery” and “serious indecency” laws, and the broader abuses against LGBTQ Barbadians to which such criminalisation contributes, have damaged too many lives — and continue to do so every day. These are the lives not only of LGBTQ Barbadians, but of their family members and friends who have lost loved ones to violence or HIV, or when those facing persecution have sought asylum elsewhere.

Despite repeated calls from domestic and international bodies for the repeal of the buggery law, successive Barbadian governments have steadfastly refused to do so. Instead government officials have prioritised the views of conservative religious groups over the lives of LGBTQ citizens. Furthermore, there is no likelihood that, within any reasonable time frame, a sufficient number of Parliamentarians will support legislative reforms abolishing the law. Any proposal for decriminalisation already encounters substantial backlash and hostility.

But it is the mark of a free and democratic society that fundamental rights and freedoms are to be universally enjoyed by all persons. Respect for human rights cannot depend upon the approval of a majority, or else the rights of any person or community is at risk. The Convention is an essential manifestation of Barbados’s commitment to basic democratic principles, and the rights it protects must be guaranteed for all Barbadians.

7. How can these laws be challenged?

The Constitution of Barbados includes a “savings clause” (section 26), which is designed to prevent the country’s domestic courts from constitutionally reviewing any laws passed before independence (in 1966), unless and until such a law is amended in some way by Barbados that introduces a new, unconstitutional aspect — at which point it would be subject to constitutional challenge. The “savings clause” therefore appears to prevent a constitutional challenge in Barbadian courts to the criminalisation of “buggery,” which was first outlawed by Britain in 1868 during the colonial era and then preserved in subsequent legislation after independence, including the current SOA enacted in 1992. (The “serious indecency” offence was first introduced in 1978, but modelled on colonial-era British law criminalising “gross indecency.”)

Therefore, the only avenue available to challenge the buggery law is to take it before international tribunals whose jurisdiction Barbados recognises. These include the IACHR and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. Both of these bodies are supposed to ensure that ratifying countries comply with the Convention. Barbados became a full party to this treaty in 1981.

Individuals can file petitions with the IACHR requesting a hearing on their state’s compliance with the provisions of the Convention. If the state’s laws are found to be in violation of the Convention, the IACHR can recommend that the state change its laws. If the state fails to comply, the IACHR can take the state to the Inter-American Court. The Court can make a binding decision obliging the state to end any breach of the Convention, including by changing its laws.

8. What is the ultimate goal of this petition?

The goal of this petition is to end the criminalisation of consensual sexual activity between persons above the age of consent, in particular the criminalisation of consensual sex between partners of the same sex. This can happen if Barbados acts on a suitable recommendation of the IACHR; alternatively, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights can issue a binding decision ordering Barbados to comply with its obligations under the Convention.

The petitioners argue that, in order to comply with the Convention, Barbados should repeal the criminal prohibitions on “buggery” (SOA section 9) and “serious indecency” (SOA section 12) in their entirety, so as to decriminalise consensual sexual activities (including anal sex) among persons above the age of consent established elsewhere in Barbadian law.

The petitioners are also asking the IACHR to recommend a number of proactive measures to be taken by Barbados to better protect LGBTQ people from the discrimination, harassment and violence to which this criminalisation has contributed. Barbadian law would continue to criminalise non-consensual sexual contact of any kind (including anal sex) under SOA section 3, which prohibits rape, and sections 4 and 5, which prohibit sex with those under the legal age of consent. These are appropriate limits on the use of the criminal law in a free and democratic society.

9. What is the likely timeline for the petition?

Petitions should be given priority by the IACHR as they concern fundamental rights and freedoms. Furthermore, the violation of such rights continues each day the criminal prohibitions remain in effect, along with the stigma, violence and abuse against LGBTQ people they encourage.

However, the IACHR receives numerous petitions each year from across the Americas, so the processing time is slow. The IACHR also encourages friendly settlement of disputes and allows the petitioners and the state time to exchange documents over a lengthy period in order to try to resolve the issue.

If no friendly settlement is possible, the IACHR will hold a hearing. If the IACHR finds that Barbados’s laws violate the Convention, it should recommend that Barbados make changes to bring its laws in line with its human rights obligations under the treaty.

If Barbados refuses to implement the IACHR recommendations, then the IACHR may take the matter to the Inter-American Court for a hearing. The Court may issue a binding decision to the state of Barbados compelling them to make the required changes. It could take years before there is a final resolution.

10. Why was the matter not tried in Barbados?

As noted above, there is a provision in the Constitution of Barbados (section 26) that prevents the country’s domestic courts from constitutionally reviewing any law passed before independence in 1966, unless and until that law is amended in some way that introduces a new, unconstitutional aspect. This includes the prohibition on “buggery” (SOA section 9), as this were originally imposed by Britain in 1868 during the colonial period and preserved after independence, carried forward into the SOA enacted in 1992. Therefore, the only avenue available to challenge this law is to take it before international tribunals whose jurisdiction Barbados recognises. These include the Inter-American Commission (IACHR) and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

11. What does such a challenge mean for people of faith? What about marriage rights for same-sex couples?

It is regrettable that proposals for repealing Barbados’s discriminatory laws have encountered opposition from some vocal, organised religious leaders who continue to foment misinformation, widespread homophobia and support for maintaining these criminal laws. Fortunately, a growing number of leaders, from various religious traditions, have begun to speak out against such discrimination and to challenge the misinterpretation and misuse of religious teachings to justify criminalisation and discrimination. They have begun to articulate a vision of a more respectful society, which is also based on the core values of their own faith tradition.

Some religious leaders have attempted to conflate calls for decriminalising consensual sexual activity by LGBTQ people with legislating same-sex marriage. This position is misguided and illogical. This petition challenges the unjustifiable criminalisation and punishment of consensual sex between people above the age of consent. Nothing in the petition before the IACHR addresses the question of granting marriage rights to same-sex couples. Decriminalising LGBTQ people (and indeed heterosexuals who also engage in consensual anal sex or other consensual acts that could fall afoul of the broad offence of “serious indecency”) does not mean legalising same-sex marriage in Barbados, nor does it compel religious leaders or organisations to perform or recognise such marriages.

Nor does decriminalising consensual sex between those who are above the age of consent interfere with other people’s freedom of opinion or belief — in a free and democratic society, people are free to hold their own views, religious or otherwise. This petition is about whether the state has a place in the bedrooms of the nation — a matter of respect for privacy, dignity and equality that is important not just for LGBTQ people, but for all Barbadians. Realising the human rights guarantees in the Convention is of benefit to all and is part of the larger project of ensuring that fundamental human rights are universally respected and protected.

12. Who is supporting this legal challenge?

Widespread homophobia makes it very difficult to find local support in Barbados to pay lawyers and to provide technical assistance for such a legal challenge. This petition is being brought by three Barbadians, with support from groups and advocates both inside and outside Barbados — including Trans Advocacy & Agitation Barbados, the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network and the University of Toronto’s International Human Rights Program, organisations that are committed to advancing human rights as a matter of basic principle and as an essential aspect of responding effectively to the HIV epidemic.

In a comment on this article on the blog’s Facebook page, a reader asked an additional question, which Maurice Tomlinson has answered:

Will the ruling be binding across all the Caribbean countries that criminalize buggery?

No. Only Barbados of the 9 countries with anti-sodomy laws recognizes the binding jurisdiction of the Inter-American Court. But, this case will provide useful precedent for court cases in each of the other countries to challenge these laws.

Related articles:

- Launching an Inter-American challenge to Barbados anti-LGBT laws (June 2018, 76crimes.com)

- With a boost from Rihanna, Barbados rejects homophobia (May 2018, 76crimes.com)

- The harshest anti-gay law in the Western Hemisphere (March 2018, 76crimes.com)

- Barbados Pride combats nation’s anti-LGBT hatred (November 2017, 76crimes.com)

- In Barbados, anti-gay march ends in mini-Pride Parade (October 2017, 76crimes.com)

- Barbados training: Police learn about LGBTI community (March 2017, 76crimes.com)

- Barbados protests seek repeal of harsh buggery law (August 2015, 76crimes.com)

- Will tourist-dependent Barbados risk staying anti-gay?

- Caribbean youths seek repeal of 6 nations’ anti-gay laws

- Queen honors LGBTI leader seeking change in Barbados

- Progress in Barbados despite harsh anti-gay law

- Barbados: No plan to drop life sentence for anti-sodomy law

- This blog’s archive of articles about Barbados

- This blog’s archive of articles by Maurice Tomlinson