New, gay-friendly faces of Jamaican dancehall music

Colin Stewart is a 45-year journalism veteran living in Southern…

Jamaica’s LGBTQ+ community is enjoying growing support from formerly homophobic dancehall artists, at least from the genre’s female performers.

Jamaica’s brave LGBTQ+ scene is nudging dancehall in a new direction, the British style magazine The Face reports. These are excerpts from the Face article “Jamaica’s brave LGBTQ+ scene is nudging dancehall in a new direction”:

By Summer Eldemire

When rising dancehall star Shenseea dropped the visuals for her summerbop Blessed earlier this year, it had all the ingredients of a classic music video set in Jamaica: the shot of a pristine beach, the man chopping a coconut, the rasta with a fat spliff chanting.

But around 13 seconds in, the camera focuses on Shenseea undressed in bed with another woman. This was radical for the Jamaican dancehall scene, and you could hope that it indicates a wider cultural shift.

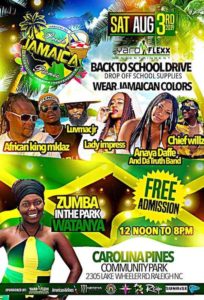

This August, Jamaican Pride took place over a six-day schedule of events including a cooler fete, a sports day, and a breakfast party – with growing support from a place where it might be least expected – from dancehall artists (although it notably only featured female performers).

It took a lot of work and courage for LGBTQ fans of dancehall to be able to celebrate like this. In 2006, Time Magazine named Jamaica “the most homophobic place on Earth.” As a genre, dancehall has produced many murderously homophobic lyrics. The most notorious song coming, of course, from Buju Banton, who gained international notoriety with his hit Boom Bye Bye, written in 1988 and released four years later.

Given the wider context, it was considered shocking when, a few days before the Blessed video dropped, Shenseea posted a picture of herself on Instagram wearing a red lacy bra with her arms wrapped around another woman. In the photo, the two are cuddling in the kind of luxurious king size bed fit for a seaside villa with the mystery woman’s bottom angled perfectly at the camera. In the second picture they appear to be kissing. The caption was “Thanks for being here… #life#love#blessed.”

The internet went wild. Some had the mindset of Jamaicans of yesteryears, such as the user who commented “Your bio says trust GOD and god don’t love batty gyal.” Another user commented: “This is a disgrace to Jamaica.” Local selector FootaHype wrote “a this dancehall gone to ….. disappointed is not even the word.” When a fan commented to defend Shenseea, FootaHype responded “di whole a unu a some big stinking dutty lesbian God a go fuck up the whole a u, just wait.” But many other fans were supportive.

Shenseea is no stranger to the LGBTQ community. Last year during Pride, she posted a picture of herself on Instagram – wearing rainbow coloured suspenders and shoes – captioned “…today I just wanna represent and tell y’all that your sexuality doesn’t matter to me I love all of y’all …#loveislove.” Other dancehall artists such as Jada Kingdom and D’Angel (ex-wife of Beenie Man) also came out in support of the LGBTQ community when she performed at Jamaica Pride last year.

Jaevion Nelson, the executive director of J-Flag, the main advocacy group on the island, wrote a Facebook post at the time, calling Shenseea’s pictures “raw, radical, and disruptive.” But he wasn’t without his hesitations. “To me, it illuminates the changes happening in Jamaica by people who are defying cultural and religious dictates, though not on a wide scale.”

For Nelson, there’s nothing inherently homophobic about Jamaican music.

“Dancehall music is resistance; it is protest and it forces us, in its own unique ways, to confront things many of us are unwilling to talk about and address – whatever the outcome,” he says. “Dancehall music tells us about life from different standpoints. It’s the lens through which many of us see our country and the world. It shapes our world view because it gives us a deep dive into our struggles, our sexual desires, our egotistical ways, and our views on various issues. Unfortunately, this sometimes comes with hugely problematic and sometimes violent lyrics which negatively affect some people – not just LGBTQ people.”

Suelle Anglin, the associate director of marketing at J-Flag, told me that many in the community appreciated the love and support from Shenseea, while others felt it might be more of a marketing ploy. Anglin felt Shenseea’s support and interaction with the LGBTQ community in the past made the artist more welcome, but she also argued that the video only happened because it featured girl-on-girl action, playing into the ongoing fetishisation of femme lesbians. “This simply would not happen with male artistes.”

Sex between two men remains illegal in the country under the buggery law, a hangover from the colonial era enacted in 1864. Consensual sex between women is not criminialised, perhaps because it is hardly recognised. In recent times, the number of mob killings of LGBTQ community members such as Dwayne Jones, a transgender teen murdered by a mob in 2013, has started to wane. J-Flag received 261 reports of human rights violations between January 2011 and January 2017. Between 2017 and 2018, they only received 15. …

Jamaica’s violence epidemic began in downtown Kingston in the ‘70s – around the same time that the dancehall genre became popular – when the two main political parties corralled their supporters into public housing and gave guns to warring gangs. Violence has held a tight grip around Jamaica since and the country has remained in the list of the top ten most murderous countries for the past decade. …

“Being a bad man is the top of the hierarchy in Jamaica,” says Donna Hope, Professor and Socio-Cultural Analyst and the University of the West Indies. Hope has studied dancehall for over 20 years, and says the homophobia is rooted in the island’s history of colonialism and slavery. A time in which Africans were brought over to the Caribbean not as humans, but as labour. “Their sexuality and masculinity became very important as a way of displaying dominance,” says Hope. This hyper masculine culture has manifested itself in dancehall as lyrics about violently suppress one’s enemy, who has the bigger guns or who has the most women. Pledging to violently attack gays was just one of the trends in the ways Jamaican artists asserted their masculinity, which was then reflected in their music.

Hope has whitnessed homophobic lyrics in dancehall soften over the past ten years. “These displays of hyper-masculinity have always been there, it’s just transformed.” Violent imagery still appears in dancehall lyrics, it’s just less likely to be directed specifically at the LGBT community.

Although Hope classifies Jamaica as a patriarchal society, women are incredibly strong figures – according to the International Labour Organisation, Jamaica is the country in which you are most likely to have a female manager, The strong presence of women could be another threatening factor to men, fuelling their need to display hypermasculinity. Something like giving oral sex to women is looked down upon in Jamaica, and is called “bowing”, as if the act means you are submitting yourself to a woman. It’s here that the phrase “bowcat” originates.

This year’s Jamaica Pride saw a performance from Ishawna whose 2017 song, Equal Rights, called for oral sex for women. In the chorus, Ishawna sings, “your back nah no use and you face look cute, deal with me like a bag juice / Mi say equal rights and justice, nuff ignorant people a go cuss this.” Hope argues that Ishawna’s “career has never recovered” since she dropped the song.

The day after the Blessed video dropped, Shenseea announced that she had signed to Interscope records. With the backing of an international record label, she may have felt braver to experiment outside of Jamaica’s cultural norms. But as Shenseea tries to crossover to the international market, she has faced criticism from Jamaicans. In a recent interview with Apple music she spoke in standard English instead of Patois and some Twitter users called her a sellout. “Signing to Interscope means she can do what she wants,” wrote Jamaican DJ and producer Silent Addy. But he also noted that she couldn’t be onstage kissing girls in Jamaica. “It’s going to take a big dancehall or reggae artist coming out as gay to change that and who knows when that will happen.” …

Jamaica has a long way to go in the fight for gay rights but – as this year’s Pride celebrations proved – there are more moments of joy in which to celebrate than ever. “For me, it’s about giving the community an opportunity to enjoy some of their favourites in their own spaces,” says J-Flag’s Jaevion Nelson of the music scene.

“It’s about allowing those artistes who support, love and celebrate LGBTQ people to stand up and make a statement to Jamaica, and the world, in their own unique way. It’s about interrogating and contesting the narrative about dancehall music and showing that though quite a bit of the music if problematic and sometimes violent toward the community, there are some – if even just a handful – who are challenging dominant views about the LGBTQ community. It’s about a celebration, a celebration of who we are as a people – Jamaican and queer.”