Kyrgyz homophobia surges; anti-LGBT bill lingers

Colin Stewart is a 45-year journalism veteran living in Southern…

Russia’s anti-gay attitudes are affecting Kyrgyzstan, the Central Asian country that is the subject of the Coda Story media project about the erosion of LGBT rights in Russia and the former Soviet Union. These are excerpts from that Coda Story article, including a brief update on the off-again/on-again Kyrgyz anti-“gay propaganda” bill:

A Violent Struggle Over National Identity:

Kyrgyzstan’s Beacon of Tolerance Under Threat from Manufactured Kremlin Homophobia

By Andrew North

We knock again, hard. But still there is no sound of anyone coming to the door. A journalist colleague and I had been invited for dinner at the home of Nika, a gay man who recently set up a small LGBTQ support group in Bishkek, the Kyrgyzstan capital. Only after we phone him do we finally hear muffled sounds from inside of first one, then two heavy metal doors being unlocked. “This is how we live now,” said Nika, taking in my glance at his security arrangements.

We knock again, hard. But still there is no sound of anyone coming to the door. A journalist colleague and I had been invited for dinner at the home of Nika, a gay man who recently set up a small LGBTQ support group in Bishkek, the Kyrgyzstan capital. Only after we phone him do we finally hear muffled sounds from inside of first one, then two heavy metal doors being unlocked. “This is how we live now,” said Nika, taking in my glance at his security arrangements.

Two years ago, the Kyrgyz parliament followed the lead of its powerful near-neighbor Russia and introduced a series of amendments outlawing the promotion of same-sex relationships. Popularly known as the ‘anti-gay propaganda law,’ it has unleashed a campaign of violence and intimidation against the LGBTQ community, with a near 300 percent increase in reported attacks since the legislation was announced. Some people have been savagely assaulted, including one gay man we interviewed who was beaten unconscious and gang-raped this year. Several sources told us of lesbians being subjected to so-called ‘corrective rapes’, and many attacks go unreported. LGBTQ activists have gone underground after the Bishkek office of one advocacy group was firebombed. …

It was never easy being lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender in Kyrgyzstan’s patriarchal, Muslim-majority society. Nonetheless, in a region where the Soviet past hangs heavily and ossified dictatorship is the norm, the smallest of the Central Asian ‘Stans’ was seen as a relative beacon of tolerance and democracy. And while there were occasional attacks in the past, the LGBTQ community was mostly left to itself. Until recently there were even several gay clubs in Bishkek. But over the past few years, internal and external forces have “dragged the LGBT community into a battle for Kyrgyz identity,” said Medet Tiulegenov, chair of international and comparative politics at the American University in Bishkek.

Poor and landlocked, Kyrgyzstan has been a geopolitical and economic supplicant ever since it became independent after the collapse of the Soviet Union, always vulnerable to bigger powers. While the US needed the Manas airbase outside Bishkek after 2001 to ferry troops in and out of Afghanistan, the Kyrgyz government tilted westwards.

But the Kremlin proved the greater force, unhappy at an American presence in its backyard, and successfully pressed Bishkek to close the base. And since winning power in 2011, President Almazbek Atambayev has cemented this shift away from the West towards Russia. “We cannot have a separate future,” he declared when President Vladimir Putin visited Kyrgyzstan in 2012.

He has been an assiduous courtier, extending Russia’s lease on its own military base outside Bishkek, before enthusiastically copying anti-Western crowd-pleasers in the Kremlin’s legal arsenal. First came a virtual clone of Moscow’s offensive on NGOs, with legislation demanding all groups receiving external funding declare themselves as ‘foreign agents’, targeted at human rights groups, including those advocating for the LGBTQ community. And then, in March 2014, MPs from the ruling coalition announced the ‘anti-gay propaganda’ measures, with even harsher penalties on paper than the Russian version. They were necessary to “protect the rights of the majority rather than of the minority,” said one of the co-sponsors, Talantbek Uzakbaev, a member of the pro-Russian ‘Dignity’ party. “We cannot tolerate gay propaganda.”

… [H]omophobic violence has risen. It’s impossible to get definite figures but staff at one Bishkek LGBTQ activist group — who asked me not to publish its name — said they’ve been helping the victims of 5 or 6 attacks a month in the past year, nearly three times the rate of two years ago. But, says Amir, one of the group’s activists, “these are only the ones we know about.” …

Russian TV channels, with their explicit anti-Western, homophobic bias, have a solid audience. “It makes me feel guilty about being gay when I hear some Russian programs,” said Nika. Local media outlets tied to the government and nationalist groups take a similar line, helping stoke an atmosphere of permissive victimization. “‘Look there’s the faggot’ another student shouted out when he saw me in my university café,” said Ilya, one of Nika’s dinner guests. There is no point going to the college authorities, he said, “because that will just bring me more trouble.” And Ilya said he was recently ejected from his gym. “The manager said other clients had complained about me being there. He didn’t say it was because I’m gay, but it was clear that’s what he meant.”

And it’s political suicide to come to the LGBTQ community’s defense, say analysts. LGBTQ advocacy groups would also be hit if the parallel ‘foreign agents’ law is passed — as most receive Western funding — but the rest of the NGO community have conspicuously avoided coming to their defense.

Yet more than two years since the Kyrgyz parliament first introduced the ‘anti-gay propaganda’ measures amid a flurry of pro-Russian rhetoric, it has stalled on actually making it law. MPs gave the bill large majorities on its initial two readings, but no date has been set for the necessary third reading, and it would still need the president’s signature afterwards. There’s similar uncertainty over the ‘foreign agents’ bill targeting NGOs, which was first introduced in 2013. And no one knows if or when parliament will debate them again. [Blog editor’s note: After this article was written, the Kyrgyz parliament resumed action on the anti-“gay propaganda” bill and rejected the “foreign agents” bill.]

Even so, the police have reportedly been using the anti-gay propaganda legislation to justify going after LGBTQ individuals and then extorting bribes. “They say they are enforcing the law,” said Pasha, a gay man who was forced to hand over 4000 Kyrgyz Som (about $60 — a large sum in a country with an average wage of less than $300 per month). Some Kyrgyz journalists have reportedly resorted to self-censoring stories on homophobic attacks, or anything to do with the LGBTQ community, in case they are accused of publishing ‘pro-gay’ propaganda. “The liberal sector in society is coming under increasing stress,” said Medet Tiulgenov of the American University.

I made repeated requests to talk to Kyrgyz MPs and other officials about their Russian-inspired legislative plans, and the associated rise in homophobic attacks. All said they were too busy, or never returned my calls. Perhaps that is a sign of what one diplomatic source calls “buyer’s remorse”, particularly over the anti-gay propaganda measures. “The president has said privately he doesn’t think it’s a good law now,” said the source, “but politically it’s hard to roll it back.”

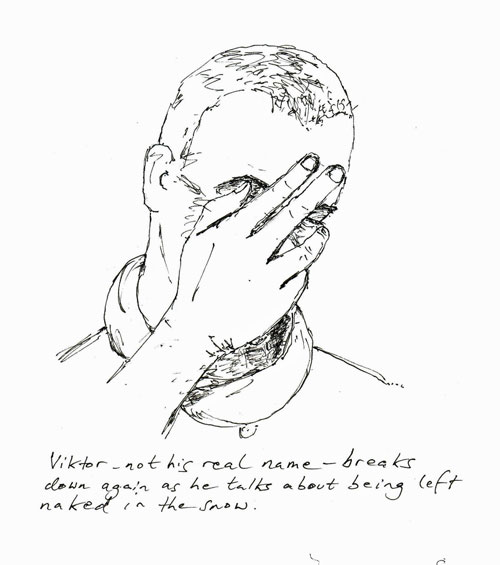

Viktor had been receiving threatening text messages for several months, messages like: “Why are you spoiling our country” and “Leave, you freak, or we’ll cut your head off.” He moved to another part of Bishkek, hoping he would be safe.

But one evening this January, walking home from work, he was ambushed and beaten to the ground. “I didn’t hear anything because I had my headphones on,” he said. “‘Why are you still here’, they were shouting. ‘We warned you we would find you.’” They kicked him unconscious, and when Viktor came round he found he had been driven to a wooded area, and his attackers were tearing off his clothes. Then they took turns to rape him. “One held my head down so I couldn’t see their faces,” he told me, pausing and sobbing several times as he tells the story. …

On May 17, 2015, activists from a Bishkek group called Labrys and several other LGBTQ advocacy organizations were gathering at a Bishkek restaurant for the ‘International Day against Homophobia and Transphobia’ when it was attacked by a nationalist mob. They stormed the restaurant, chanting abuse as they went, and one woman was injured in the ensuing scuffles. Though it was frightening, compared to other recent anti-LGBTQ violence, it was a relatively minor incident. But this time activists called the police.

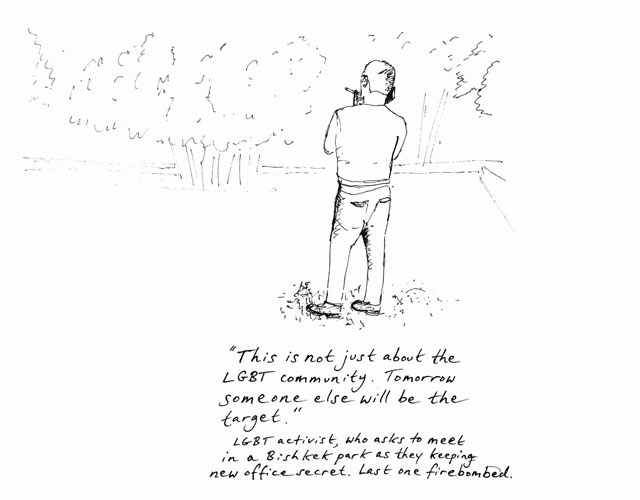

With so many eyewitnesses, Evgenia Krapivina, their lawyer, believes the police had no choice but to open a case, and two suspected members of Kyrk-Choro have been charged with hooliganism and property damage. To no one’s surprise, there’s been little progress since, and they hold out little hope of winning, but one of the Labrys activists who was there sees it as part of a much bigger battle. “The LGBT community is not the only target,” he says. “Some of the nationalists who attack us say everyone should speak Kyrgyz, and that there’s no place for Russians here. And tomorrow someone else will be the target.”

Andrew North is a freelance journalist and artist. Follow him on @NorthAndrew and see more of his work at Sketchy Reports.

For more information:

Read the full Coda Story article, “A Violent Struggle Over National Identity: Kyrgyzstan’s Beacon of Tolerance Under Threat from Manufactured Kremlin Homophobia.”

Also see related Coda Story coverage:

- A ‘Family’ Gathering Commemorates an Anti-Gay Riot. An anti-LGBTQ conference provides ecumenical and political unity among American, Georgian and Russian members of the religious right. [World Congress of Families convention in the Republic of Georgia in May 2016]

- “Permission to Exterminate” [Video] The story of one man caught up in Kyrgyzstan’s homophobic violence. [Warning: Graphic Content]

- On the Frontiers of the “Russian World”: How homosexuality got caught up in the war in eastern Ukraine.

- Clubbing and Surviving in Samara: Life in Russia’s Most Homophobic City

Related articles in this blog:

- How to protest Russia-style anti-gay bill in Kygyzstan (March 2015, 76crimes.com)

- Pressure on Kyrgyzstan to derail Russia-style anti-LGBTI bill (March 2015)

- Kyrgyz appeal for protests against anti-‘gay propaganda’ bill (October 2014, 76crimes.com)

- Kyrgyzstan plea: Please help oppose anti-gay bill (July 2014, 76crimes.com)

- Kyrgyzstan on the verge of adopting harsh anti-gay law (June 2014, 76crimes.com)