2022 in worldwide LGBT rights progress – Part 5: Europe

2022 turned out to be a major year for the advancement of LGBT rights with huge developments in every corner of the world. To celebrate this progress and highlight some of the challenges ahead for the global LGBT community, 76crimes is presenting this six-part series looking at the wins and losses queer people achieved in 2022.

Europe is traditionally where we see a lot of major progress on LGBT rights given its large number of democracies with generally tolerant attitudes. This year was no different, but the headline issue in 2022 was the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine that began in February. While the invasion has obviously had an incredible impact on LGBT people in both countries, it also had ripple effects across the continent.

This article originally appeared on 76crimes Contributing Editor Rob Salerno’s personal blog.

Earlier in this series – Part 1: North America | Part 2: Latin America and Caribbean | Part 3: Africa and Oceania | Part 4: Asia

Fear of Russian aggression largely drew European countries closer together, deepening and accelerating the process of European/EU integration. This is important, because the EU and its institutions themselves have been big drivers of LGBT rights progress. There’s also been a bit of an element of ‘compare-and-contrast’ against the Russian government’s deep antipathy toward LGBT people that has motivated some progress in Europe — and exposed potential fault lines among the allies.

We’ll get to Russia and Ukraine in due time, but first, we’ll start with the European country that took the biggest leap forward in LGBT rights this year.

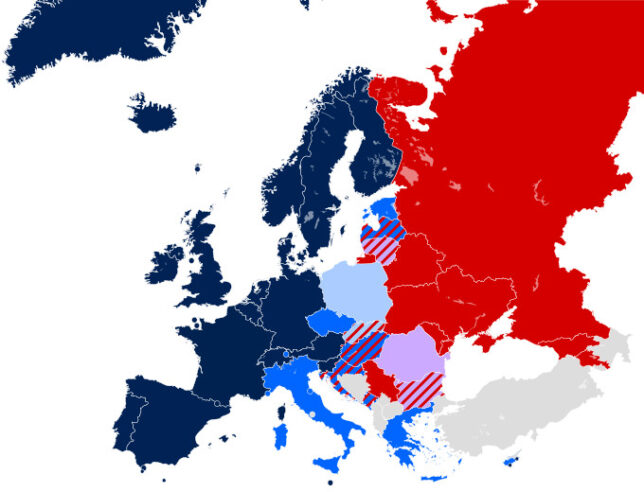

DARK BLUE: Same-sex marriage legal

BLUE: Same-sex civil unions legal

LIGHT BLUE: Very limited cohabitation recognition possible

MAUVE: Limited recognition of foreign same-sex unions (residency)

RED: Constitutional ban on same-sex marriage

GREY: No recognition

Western Europe

Andorra: The tiny principality between France and Spain finally passed its reformed Family Code, which includes a number of legal advances for LGBT people. The headline is that the law allows same-sex civil marriage for the first time, although there was a strange terminology question involved. The bill referred to those marriages as “casament civil,” while religious marriages were called “matrimoni,” but also clarified that “casament” is a form of “matrimoni.” To make things more confusing, both words translate from Catalan to English as “marriage.” The opposition parties held up the bill for more than a year over this issue, and after it passed, they took the law to court to ask a judge to erase the distinction. That case was resolved in December when the Constitutional Court ruled the distinction illegal, so now all couples can access “matrimoni.”

The new Family Code also gives trans people the right to change their legal name and gender, and allows single women and lesbian couples to access IVF. All of these should help the country bounce a few pegs up the ILGA Rainbow Europe scoreboard. What won’t help is that the new code eliminates “civil unions” as a concept in law – for some reason, ILGA-Europe wants countries to have both options, and weights them both equally, so Andorra gets no extra points for moving from civil unions to full equal marriage.

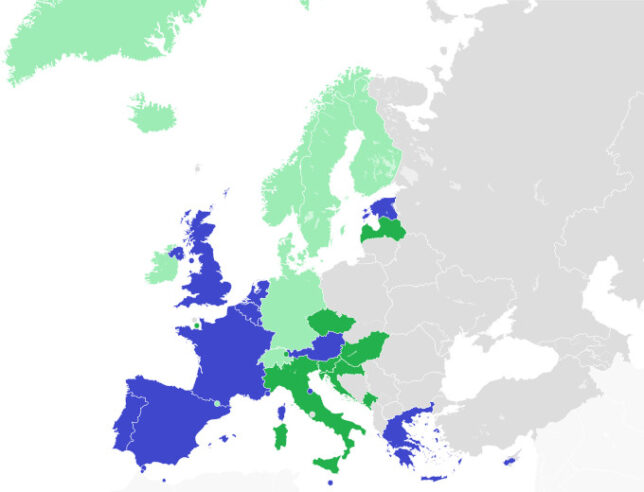

BLUE: Gender-neutral civil unions

GREEN: Same-sex civil unions only

LIGHT GREEN: Same-sex civil unions formerly possible, replaced by marriage.

Spain: The national government passed a law that bans anti-LGBT discrimination in employment and provision of goods and services. Prior to this, only sexual orientation employment discrimination was prohibited nationally, however all of Spain’s autonomous communities had also banned gender identity employment discrimination except for Castille & Leon and Asturias. Earlier this year, the communities of Castilla La Mancha and La Rioja banned gender identity employment discrimination.

A broader LGBTI rights law, dubbed the “Trans Law,” is still under consideration by the Senate, having cleared the lower house just before Christmas. The main focus of debate was on how the law greatly expands gender self-determination for trans people, but it was subject to great debate over the cut-off age below which a judge must be involved – 16, 14, 12? Once again, most autonomous communities already have gender identity self-determination, with the exceptions being Castille & Leon and Asturias, which have no legal gender change, and Galicia, where a medical diagnosis is required. La Rioja and Castilla La Mancha passed their gender identity laws this year too. Beyond the gender issues, the bill also bans conversion therapy, bans cosmetic genital surgery on intersex babies, and gives lesbians and single women access to IVF (previously banned). When all of this passes, Spain will rocket up the Rainbow Map chart — though probably not until the 2024 edition, because ILGA-Europe stops counting laws passed after Dec 31.

The government also began work on a new family law recognizing and equating a wide scope of different family types for social benefits, including those headed by same-sex couples (“homoparental” families). I don’t know if this makes any functional difference for LGBT families.

France: The National Assembly passed a bill to ban conversion therapy. The government also ended its ban on blood donations from men who have sex with men. A court found that a transgender woman should be recognized as a “mother” to her child, conceived pre-transition. And the French people managed to keep the far-right out of the presidency in national elections.

Italy: Parliament failed to pass its bill banning anti-LGBT hate crimes and discrimination ahead of elections, which put a coalition of far-right homophobic parties firmly in power. Expect no progress on LGBT initiatives from Italy for the next four years – unless the coalition somehow collapses first. During the election, both the large opposition parties, the Democrats and the 5 Stars, came out in favor of same-sex marriage. Despite losing the election, the left-wing parties got the larger share of the vote, but failed because they could not come to an electoral coalition agreement.

The courts have already slapped down one policy created by members of this new government. A new requirement that a child’s identity documents list a “mother” and “father” was ruled to be false and discriminatory. The policy remains standing, however, and same-sex couples will have to sue to obtain documents that don’t misgender them.

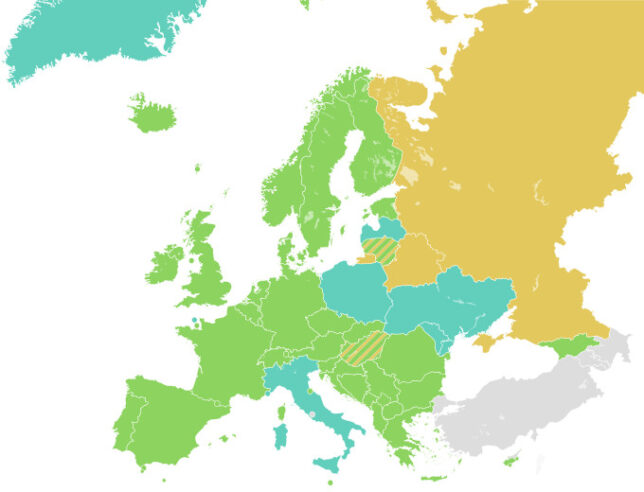

GREEN: Broad anti-discrimination protections (employment, services, hate speech)

TEAL: Limited anti-discrimination protections

YELLOW: Legal limits placed on LGBT speech and organization

Malta: The government ended the MSM blood donation ban.

Belgium: The cabinet proposed a bill to ban conversion therapy, but contrary to some reports, Parliament hasn’t even debated it yet, let alone passed it. Also during the year, it was reported that certain Catholic churches in Belgium were blessing same-sex marriages, in defiance of the Vatican.

Netherlands: The lower house passed a bill that would add sexual orientation and disability as prohibited grounds of discrimination under the constitution – it now needs to be ratified by a 2/3 majority of the Senate.

As discussed in the section on the Americas, the Dutch constituent countries Aruba and Curacao were subject to a court ruling requiring them to allow same-sex marriage, but the decision is currently stayed pending a possible appeal. If it stands, it is likely that the remaining country, Sint-Maarten, with have its ban challenged as well.

Luxembourg: The grand duchy didn’t record any legislative progress on key issues for the LGBT community, which is seeking a ban on cosmetic surgeries on intersex children, and automatic parental recognition for same-sex parents.

United Kingdom: The UK lurched from crisis to crisis this year and got very little accomplished under three separate Prime Ministers and two monarchs. In January, the government announced a plan to purge all historical anti-gay convictions, but nothing has been heard of it since. No progress was made on a long-promised ban on conversion therapy, after the Boris Johnson government flip-flopped for months on whether it would include protection for trans people – his successors have been mum on the subject.

In small victories, the government ratified the Istanbul Convention on Domestic Violence, which includes inclusive language for LGBT families, and Wales added compulsory, inclusive sex education to its school systems. Northern Ireland’s government received a report calling for reforms to its gender recognition laws, but it also failed to have a government for most of 2022, largely because the anti-LGBT DUP refused to join an executive after it lost the May elections, and the province requires the largest unionist and republican parties to share the executive to function. The UK government has been trying to force the parties together, but may instead call new elections in April.

Scotland’s parliament passed a law allowing trans people to self-determine their legal gender right before Christmas, but the UK government has announced it may block it from receiving Royal Assent. Scotland is also working toward its own comprehensive conversion therapy ban.

Among the Crown Dependencies, the Isle of Man announced that it was working on ending the MSM blood donation ban, with a target of 2023 to revise its systems. Last year, Jersey and Guernsey said the same thing, but I can’t find any information indicating they did so.

As discussed in the section on the Americas, the Privy Council ruled against same-sex marriage in the UK territories of Bermuda and Cayman Islands, a separate same-sex marriage case is winding through the Virgin Islands courts, and a UK Lord has proposed a bill that legalize same-sex marriage in all six remaining UK territories (the others are Anguilla, Montserrat and Turks & Caicos Islands.) All UK territories are bound by the European Convention on Human Rights to implement at least some form of relationship recognition for same-sex couples.

Ireland: The government eliminated the blanket ban on blood donation from men who have sex with men. Cabinet approved adding protections for transgender people into hate crime laws, but the bill must still be passed by Parliament. A long-proposed conversion therapy bill remained stalled in Parliament.

Central Europe

Slovenia: In July, the Constitutional Court ruled that excluding same-sex couples from marriage and adoption was unconstitutional, with immediate effect. The government welcomed the decision and codified it into law by October. This was a partial reversal of the 2015 referendum that overturned the government’s previous attempt to legalize same-sex marriage. This time, the court ruled that a referendum proposed by anti-LGBT groups seeking to overturn the decision and the law could not go ahead.

Also this year, the ban on blood donation from gay men was lifted, following a report from the equal opportunities ombudsman last year.

Croatia: The High Administrative Court rejected the government’s appeal of a 2021 decision that same-sex couples have a right to joint adoption. Croatia also deepened its ties to the EU – it will adopt the euro currency and join the Schengen free-travel area on January 1.

Switzerland: The law allowing same-sex marriage, adoption, and IVF came into effect in July, following last year’s referendum. Also coming into effect in January 2022 was a new law allowing gender identity self-determination. The federal parliament began discussion on a proposed conversion therapy ban and the government began discussions on ending the MSM blood donation ban.

Liechtenstein: Last year, the State Court gave the government one year to amend the law to allow same-sex couples in registered partnerships to adopt. The government presented a bill that would allow same-sex couples stepchild adoption only, but Parliament rejected it, meaning that full joint adoption became technically legal in July. The government accepted Parliament’s decision and eventually presented a bill to codify the court’s ruling into law in December. I believe the bill also grants access to reproductive medicine (eg., IVF) for same-sex couples. It will likely be debated and passed early next year.

Previously, the main obstacle to same-sex marriage was the Prince’s stated opposition to allowing same-sex couples to adopt, but this was now moot, so LGBT activists took advantage of the moment to push for full equal marriage. It obviously helped that all the other German-speaking countries have already legalized it. In November, Parliament passed a motion calling on the government to introduce a same-sex marriage bill. If the timelines sticks to recent patterns, I would expect to see a bill sometime in the spring, followed by a few months of debate and consultation ahead of a vote, and then possibly up to a year before the law takes effect sometime in 2024.

The government also approved a report that noted that the current language of the registered partnership law is gender-neutral, meaning it is technically already open for heterosexual couples, though none is known to have availed themselves of it.

As discussed below, the blood donation ban was scrapped by Austria, which manages Liechtenstein’s system, this year.

Austria: The government ended the ban on blood donation from gay men. Since they share a blood system, the end of the ban also applied to neighboring Liechtenstein. The government shelved proposals to allow automatic parenting recognition for same-sex couples and to broaden sex education, and has failed to introduce a long-proposed conversion therapy ban.

Germany: The new government created a Commissioner for Acceptance of Sexual and Gender Diversity and launched plans to make it easier for trans people to change their legal name and gender, and to allow a nonbinary option for anyone (currently restricted to intersex people).

Eastern Europe and Southern Balkans

Czechia: No progress was made on same-sex marriage under the new Parliament elected last October. A same-sex marriage bill was submitted with support from a cross-Parliament group of five parties, but although four of those parties are part of the governing coalition, it didn’t enjoy support from the government itself (which includes Christian Democrats, who are generally opposed).

In addition, the President threatened to veto same-sex marriage if it came to his desk, but that isn’t much of an issue because veto can be overridden with a simple majority vote of MPs, and the President’s term ends in early 2023. The first round of the Presidential election is Jan 13-14, and all three leading contenders have expressed support for same-sex marriage and adoption rights.

Equal marriage has long held majority support in polls in Czechia, and even enjoyed government support under previous PM Babis, who is now running for President. And yet, that support has rarely motivated legislators to act.

Could 2023 finally be the year that changes things? If so, it would be the second Slavic and post-communist country to legalize same-sex marriage after Slovenia did this year, and the first post-Warsaw Pact country to do so (yes, we’re really splitting hairs here!).

Slovakia: A teenage gunman murdered two gay men outside a Bratislava gay bar before turning the gun on himself in a hate crime that shook the nation and made headlines around the world. Unfortunately, it did not seem to move many politicians, who voted down a bill to create very limited registered partnerships for same-sex couples, only a few days later.

It should be noted again here that nearly every country in Europe (except Belarus and Russia) is obligated to create some form of relationship recognition under the European Convention on Human Rights, as determined by the 2015 ECHR ruling in Oliari and Others v. Italy.

The government introduced and then quickly revoked standards of medical care for transgender patients. Consequently, there were no longer any standards for legal gender change, and health care providers have been reluctant to treat trans patients seeking gender-related care. The Supreme Court later stepped in to rule that surgery and castration is no longer required for legal gender change.

Hungary: Democracy activists suffered a major defeat as autocratic and homophobic Prime Minister Orban won reelection in April, defeating a broad coalition of parties that had agreed to a progressive agenda just to get rid of Orban. A referendum to endorse the government’s strict law against “promotion of homosexuality” held at the same time failed due to low voter turnout.

The law, and Hungary’s general antipathy toward rule of law, democracy, and financial transparency, have been a major source of friction between Hungary and the rest of the EU. The EU has withheld much-needed financial assistance from Hungary, and Hungary has responded by vetoing EU programs, including most recently, holding up aid for Ukraine. Hungary reached an agreement to unlock those funds, only for the EU to block an even larger amount of regular funding to Hungary (€22 Billion) right before Christmas over those same concerns. To put that in perspective, that’s about €2,200 per Hungarian, or about 13% of the country’s GDP. Hungary has also withheld ratification of Sweden and Finland’s accession to NATO and refused to allow arms to flow to Ukraine through its territory — expect Hungary to try to trade the NATO vote to unlock those funds.

If anything is giving EU states hesitation about expansion, it’s Hungary’s deep democratic backsliding and intransigence over the past decade. None of the other members want to see the union held hostage by a half-dozen Orbans in a decade.

Poland: At the end of the year, the Polish government announced it would veto proposed EU regulations that would require all states to recognize parental relationships established in other states, including same-sex parents. It’s unclear how this will all shake out in the end.

Polish opposition leader Donald Tusk, who is gaining in opinion polls ahead of next year’s election, has promised to introduce same-sex civil unions and legal abortion as part of a campaign to modernize Poland if elected.

Also this year, the top appeals court ordered that four so-called “LGBT-Free Zones” be scrapped, the president twice vetoed a proposed education law that opponents said was designed to give the government power to exclude LGBT issues from schools, and Warsaw hosted KyivPride, due to the war in Ukraine.

Oh, and remember those “LGBT-free zones” from a few years ago? Some activists have made an updated “Atlas of Hate” marking where they are, including those that have been repealed, and areas facing continued lobbying from anti-LGBT activists to initiate them.

Romania: The Senate passed a “gay propaganda” law that would ban information about LGBT people and sex education for minors. It would also forbid minors from changing their legal gender. It awaits a vote in the Parliament’s lower house.

Bulgaria: Little happened here, as the government was mired in a political crisis for much of the year. Bulgaria formalized its plan to join the Eurozone, which it is expected to do on Jan 1, 2024.

Romania and Bulgaria were both blocked from joining the Schengen Area by Austria and Netherlands, but both believe they will be approved to join Schengen later in 2023.

Greece: Opposition leader and former Prime Minister Alexis Tsirpas came out in support of same-sex marriage and joint adoption and submitted a bill to legalize it in Parliament. He stands a decent change of leading the government again after July 2023 elections.

Meanwhile, the current government banned unnecessary surgery on intersex children, banned conversion therapy, and ended the MSM blood donation ban.

Cyprus: A conversion therapy ban was debated in Parliament shortly after Greece passed its own ban. It is still in progress. Look for same-sex marriage to become a live issue here if Greece legalizes it next year.

The government also eliminated a ban on blood donation from gay men and Parliament voted 39-4 to introduce mandatory, LGBT-inclusive sex education in schools.

The dispute with Turkey over Northern Cyprus remained a key flashpoint of conflict in the region. In one sign of peace and progress, the first Intercommunal Pride parade was held, in which marches from the North and the Republic met in the UN Buffer Zone between them.

Turkey: The increasingly authoritarian government in Turkey continued its crackdown on LGBT rights, banning Istanbul Pride for the eighth consecutive year. Marchers showed up anyway.

Despite being a NATO ally, Turkey spent much of the year attempting to play both sides in the Ukraine conflict, refusing to join sanctions against Russia, holding up Sweden and Finland’s accession to NATO, and directly threatening to invade its neighbors – EU members Greece and Cyprus, as well as Syria. After all, Erdogan and Putin have a lot in common, as quasi theocratic autocrats who hate queer people. The difference is that Erdogan faces a competitive election next year.

Erdogan is trying to galvanize support by ginning up opposition to queers. He plans to put a constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage on the ballot during the next election. It’s not entirely clear that this will generate much of an advantage for him, as the opposition doesn’t seem to be taking the bait to oppose the amendment. At time of writing, Parliament has not yet agreed to the referendum.

Scandinavia and Baltics

Denmark: Denmark joined the LGBTI Core Group at the United Nations. It also deepened its Euro-integration this year, by abolishing its previous opt-out of the common defense policy.

The Faroe Islands, one of its constituent countries, passed a law last December to grant equal parenting recognition for LGBT couples – including automatic parentage, parental leave, and inheritance. I assume it was ratified by Denmark early this year. Local elections this December returned a progressive majority for the first time in ages, leading some to hope that a comprehensive LGBT anti-discrimination law might finally be passed in the new year.

Sweden: The government proposed to reform the gender identity law, but no progress has been made on it. Both Sweden and its neighbor Finland abandoned neutrality and deepened Euro-Atlantic integration by applying to NATO, which they expect to join in the new year (after holdouts Hungary and Turkey ratify).

Both countries also have proposals to ban conversion therapy, but neither has advanced. In Finland’s case, it came from a popular petition to Parliament last year.

Norway: On the 50th anniversary of the repeal of anti-gay laws, the government delivered a formal apology to all victims of the law.

Iceland: Parliament approved a resolution to reduce or eliminate the gay blood donation ban, but the actual ban is still in place. The government plans to announce a new policy and launch it in the new year.

An opposition MP also introduced a bill to ban conversion therapy, but it hasn’t advanced. The current government is dominated by conservatives.

Parliament passed a detailed LGBTI Action Plan for 2022-2025 in June, but it mostly refers to studies and training for government workers. It does set as a goal making Iceland one of the top states in ILGA-Europe’s Rainbow Map (it’s currently 11th with a score of 61%, just behind Montenegro). The main legislative commitments it includes are amending hate speech legislation to explicitly include intersex people (under the category “sex characteristics”), introducing a hate crime law, enacting regulations around trans health care, and ending the blood donor ban.

Estonia: The government continued to fail to introduce the laws that would make the 2016 civil union law effective. This leaves couples in limbo.

Lithuania: The government allowed gender and name change without surgery, but still requires a medical diagnosis of transgenderism. The government also issued the first standards of care for treating gender dysphoria. The government also ended the MSM blood donor ban.

The country’s laws restricting LGBT materials for youth were challenged in a case heard at the European Court of Human Rights. A decision has not yet been made.

Parliament also made progress on passing a limited civil union bill, which awaits a final vote, likely next year.

Latvia: A proposed civil union bill died when Parliament was dissolved ahead of elections. The elections shut out some progressive parties that just missed the threshold, putting a conservative bloc in power. An attempt to bring the bill back in the new Parliament failed.

Nevertheless, a 2020 Constitutional Court ruling ordering some form of recognition for same-sex couples stood, and Parliament missed its June 1, 2022 deadline. Since that date, same-sex couples have been able to register their relationships at court – and at least 16 couples have – although it’s not clear what rights accrue to these couples. It’s likely that will be the subject of additional litigation, unless Parliament steps up and passes a formal law.

Western Balkans EU Aspirants

Bosnia & Herzegovina: A proposed civil union bill in the federation half of the country has not advanced. Bosnia was also accepted as an EU candidate country, though its barely functional national government remains an obstacle to accession.

Kosovo: A draft civil code that included same-sex civil unions was rejected by Parliament.

Kosovo has made little progress on resolving its bilateral conflict with Serbia, as both sides took turns needling each other all year. Kosovo formally submitted an application to join the EU this year, but the organization has not made a decision to grant it candidate status yet. Five EU member states do not even recognize Kosovo as a state (Spain, Slovakia, Greece, Cyprus, and Romania). The EU did advance a proposal to allow Kosovars visa-free travel to the Schengen Area starting January 2024 at the latest.

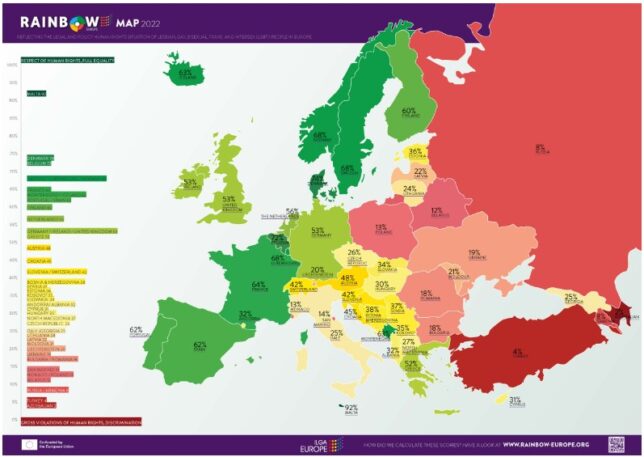

Montenegro: The big news here was Montenegro’s fantastic placement in ILGA-Europe’s annual ranking of countries based on how they treat LGBT rights. The country scored 8th out of Europe’s 49 countries, beating out notable hell holes for queer people like Germany, Netherlands, Spain, the UK, and Ireland. If you think this is surprising, you may join the other half-million Montenegrins. For a little perspective, there isn’t a single gay bar in the entire country. This, to me, indicates that there’s either something wrong with ILGA-Europe’s research or their metrics (or probably, both).

There were no notable legislative advancements for LGBT rights in 2022. Montenegro continues slowly on its path to accession in the EU, though no tangible progress was charted this year either.

North Macedonia and Albania: Both countries were allowed to begin EU accession negotiations after Bulgaria lifted its veto over North Macedonia in the summer. A possible obstacle to North Macedonia’s accession is that the deal with Bulgaria requires constitutional amendments recognizing a Bulgarian minority and culture, and the government may not have the supermajority of votes to pass it next year. The deal also requires North Macedonia to introduce a hate speech law (to prevent speech hateful of Bulgarians), which could possibly be extended upon introduction to protect LGBT people.

Serbia: A long-proposed civil union law never materialized.

Eastern EU Aspirants

Ukraine: Obviously, the government’s main focus this year has been mere survival in the face of a genocidal army. However, the ongoing war has led to some social progress to be proud of.

Ukraine got off the fence and sought membership in the EU, surely motivated by the fact that its survival as an independent state is currently in jeopardy without allies. The EU has accepted Ukraine’s candidacy, but no one believes it will be admitted soon, even after the war ends. However, it puts it on a path toward stability, democracy, and rule of law. In a bid to show off its bona fides, Ukraine took some initiatives like ratifying the Istanbul Convention on Domestic Violence (this may also have been motivated by the highly disturbing number of reports of sexual assaults committed by the invaders). Ukraine’s parliament also unanimously passed a new Broadcasting Law, which includes a ban on incitement to hatred of LGBT people — also a requirement of EU membership. It sure seems like Ukraine is taking its bid for EU membership more seriously than some of the Western Balkans countries that have been recognized candidates for a decade.

Ukraine has also made a bid for NATO membership, but no invitation has been made yet – NATO is unlikely to invite a member with an ongoing war against Russia.

There are anecdotal reports of greater tolerance for LGBT people in Ukraine these days, in the wake of many stories of queer soldiers fighting on the front lines. Many have chosen to identify themselves with unicorn badges, making them highly visible. Many people became sympathetic to soldiers who knew that their partners might not be notified or be able to retrieve their bodies if they are injured or killed in action, because there is no recognition of their relationship. Millions of Ukrainians being displaced in Western countries that have more visible gay communities may be helping as well. And polls are showing the dramatic change in attitude, with one poll suggesting antipathy toward LGBT people has dropped from 60% to 38%, while support for civil unions or equal marriage is also growing (though still not in majority territory).

In July, a formal petition was launched seeking same-sex marriage in Ukraine, and it gathered 28,000 signatures, forcing a response from President Zelenskyy. In August, he said that he supported same-sex marriage but could not amend the constitution to allow it under the state of emergency. He proposed legalizing civil partnerships and directed his government to draft a bill, but thus far nothing has materialized.

Due to the war, KyivPride was held in Warsaw this year.

Georgia: Georgia applied for EU membership, but the union decided to defer accepting it as a candidate.

Moldova: Pushed by the conflict in neighboring Ukraine, Moldova applied for EU membership and received candidate status. No one thinks it will be admitted soon, but it puts the small country clearly on a path toward liberalization.

The conflict has also, possibly, opened up the possibility of future rapprochement with the breakaway Transnistria region. Russia had been hoping to sweep through Ukraine and absorb the breakaway republic, but the halt and reversal of Russia’s advance, and the frequent cuts to Russian gas exports to the territory, have left it in a precarious position. Another possibility that had been discussed by analysts this year was that Ukraine might invade Transnistria to deny Russia an ally that would encircle it, but that does not seem to be a priority for Ukraine. EU investment in the region might help woo it back, but the territory is a basic thugocracy that the EU doesn’t seem interested in working with for good reasons.

And of course…

Russia

Russia accelerated its campaign of brutalizing its LGBT citizens – and those of other countries. It greatly expanded its “LGBT propaganda” law, banning basically all discussion or presentation of LGBT people or issues in public. This is all of a pattern with Russia’s general crackdown on opposition, pro-democracy, and anti-war voices across the country. This has included blocking or dismantling social media outlets that had previously allowed activists to amplify messages.

Of course, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine means that Russia is brutalizing the queer people of Ukraine as well – both in the territories it has illegally annexed (this blog does not recognize the annexations of Ukrainian territory) and in the territories it has been bombing since February.

The West has finally woken up to Russia’s nonsense, and sanctions against Russia have helped reduce the spread of Russian propaganda and disinformation around the world – at least through official channels like Russia’s state propaganda channel RT, which previously had licenses around the world. Russia has continued to use social media to spread anti-LGBT hate around the world, often on official embassy channels and directed at western politicians. The irony that they can do this in the west while they block Facebook, Instagram and Twitter domestically is apparently lost.

Another consequence of the invasion is that Russia was finally booted from the Council of Europe, an organization distinct from the European Union which includes all European states (except Belarus and now Russia) which is dedicated to promoting pan-continental peace and human rights, principally through the European Convention on Human Rights and its Court. Russia has also denounced the Convention. As a consequence of either action, Russian citizens can no longer bring human rights complaints to the court (a key reason why certain Western nations were hesitant to take this step previously), but to be quite blunt, Russia wasn’t following the rulings of the court anyway — notably for our purposes, it rejected ECHR findings against its gay propaganda law and its banning of Moscow Pride. Meanwhile, cases from Russia created a huge workload for the court (reportedly 25% of all cases in 2008), which backlogged cases from other countries. Russia’s denunciation of the treaty also means it is not obligated under the the Court’s 2015 ruling in Oliari and Others v. Italy to establish civil unions for same-sex couples (though again, it was extremely unlikely that Russia would ever implement the ruling).

On Monday, we’ll wrap up this series with a look at a few key International Organizations and a look forward to trends we’re hoping to see in 2023.