Cameroon: A productive life wrecked by homophobia

Colin Stewart is a 45-year journalism veteran living in Southern…

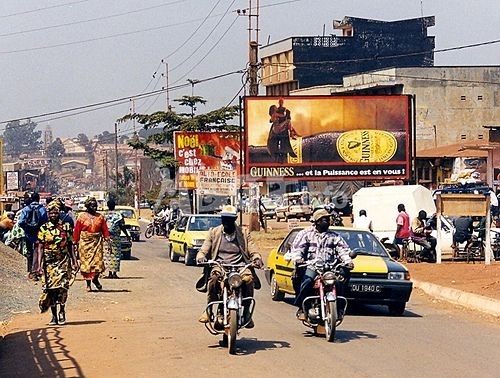

For five months, Maxime, 26, had lived in a room in the Mimboman neighborhood of Yaoundé, earning his living by selling braised fish.

In that densely populated area where homes butt against each other, his neighbors included his landlord and the landlord’s extended family.

All seemed well until one day in June, when Maxime was doing the dishes. A neighbor, Roger, age 30, his landlord’s brother, appeared at his door and told him to move out of the room without delay.

Surprised, Maxime asked him why. Roger’s wife then joined the conversation, saying, “We will go to the police to denounce what you do in your bedroom.”

Maxime ignored their demand, but his days of friendly relations with his neighbors were soon at an end.

A few days later, when Maxime went to the market with a neighbor who let him store his fish in her refrigerator, her husband commented, “Maxime, I didn’t know you were here, but I came with your neighbor Roger. He says you are a homo and, if you deny it, he will prove it to you by A + B.”

Maxime decided to visit his landlord to outline the situation and to explain what the brother was doing. But while he talked to the landlord, Roger appeared, insulting Maxime and threatening to beat him.

Afraid, Maxime fled to his room. He was followed by Roger’s wife and daughter, who shoved him and continued the insults:

“Uh, oh, homo, you’re not going to sleep in this room today! “

Maxime feared he would be lynched.

He refused to move out that day. In fact, he held firm for a month, but every day he had to endure more insults. His homophobic neighbors threatened to track him down wherever gays gather and “throw a party” for him.

Roger didn’t relent. On the contrary.

He urged Maxime’s neighbor to stop letting Maxime use her refrigerator. He threatened that, if she didn’t, he would report her for promoting homosexuality. He threatened a woman from whom Maxime rented space where he prepared and sold braised fish. Roger told her to evict Maxime and, if she didn’t, Roger said he would buy the location himself and evict them both.

The landlord began supporting his brother: He cut off Maxime’s electricity and blocked his access to the toilet.

After a month of such hostility, Maxime moved out. At the same time, his business collapsed, because Roger’s threats succeeded in evicting him from his braised-fish store.

Maxime turned for help to the LGBTI rights advocates at Camfaids (the Cameroonian Foundation for Aids). They helped Maxime file a complaint against Roger at the 16th district police station in Mimboman.

On the day of the confrontation, Roger did not attend, but his wife did. Before the hearing got under way, Maxime experienced the type of frustration that homosexuals in Cameroon know all too well.

When he asked the police investigator, Anicet Tama, what could be done about Roger’s absence, Tama told him that the hearing would not proceed unless Maxime brought in a certificate proving that he is not homosexual.

In Cameroon, you see, homosexuals have no access to justice. They have no rights.

Camfaids advised Maxime to hire a lawyer, but he had too little money even for a lawyer’s preliminary investigation (20,000 CFA francs, or about US$43). Maxime’s situation was so precarious that he did not even have than much money. He was now homeless.

He found refuge for two months in a safe house run by the LGBTI organization Affirmative Action, also based in Yaoundé.

Maxime remains there today — idle, with no income, his business defunct.

Yaoundé’s LGBTI groups are helping him get by and, perhaps, get his life back in gear. The LGBTI association Humanity First provided him with psychological counseling. But that’s a palliative, not a cure.

What he needs is a way to earn a living again.

Every night, like clockwork, he thinks fearfully about the next day. Every morning, he opens his eyes and wonders how to rebound, how to find money to relocate and get back to work.

Every day he wonders how he can get back on his feet, how he can regain his dignity.

Related articles

- Life is tough for trans and intersex Cameroonians (76crimes.com)

- Cameroon landlords evict 2 groups serving LGBTI (76crimes.com)

- Gay in Cameroon: National team bans fastest-ever hurdler (76crimes.com)

what a shitty country…

Reblogged this on Fairy JerBear's Queer/Trans News, Views & More From The City Different – Santa Fe, NM and commented:

A story of gross injustice perpetuated in a country with officially sanctioned homophobia.