HRW exposes LGBT human rights abuses in Ghana, Kenya and Rwanda

Colin Stewart is a 45-year journalism veteran living in Southern…

Arbitrary arrests in Ghana. Homophobic censorship in Kenya. Round-ups of LGBT people in Rwanda. Human Rights Watch turned a spotlight on each of those abuses in recent days.

These are excerpts from HRW’s recent coverage of:

Extreme Anti-LGBT Bill Stokes Hostility

Ghana: LGBT Activists Face Hardships After Detention

Arbitrary arrests and detention of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people in Ghana, and a proposed draconian anti-LGBT bill are causing serious economic hardship and psychological stress for LGBT people, Human Rights Watch has found.

In July, eight members of parliament introduced the Promotion of Proper Human Sexual Rights and Ghanaian Family Values Bill 2021, which would proscribe and criminalize any advocacy of LGBT identity. It is an affront to dignity, privacy, and non-discrimination, and an assault on freedoms of speech, expression, association, and assembly. The bill is currently under review by the Parliamentary Select Committee on Constitutional, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs.

LGBT people already face harsh and arbitrary punishment in Ghana. On May 20, 2021, police in Ho, in the Volta region, raided and unlawfully arrested 21 people, including a technician, during a paralegal training workshop about how to document and report human rights violations against LGBT people. They were detained for 22 days, then released on bail, and charged with unlawful assembly, a misdemeanor. The case was later dismissed for lack of evidence of a crime.

Police erroneously justified the arrests on the grounds that the training session was “promoting homosexuality” and that the gathering was an “unlawful assembly.” Section 201 of the Ghana Criminal Code (Amendment) Act 2003 (Act 646) defines an unlawful assembly as a gathering of three or more people with the intent to commit an offense, clearly not applicable in this case, Human Rights Watch says.

“It is shocking that the police who should be protecting Ghanaians raided a peaceful meeting, arrested the participants, and subjected them to three weeks in harsh detention conditions on a charge that never should have been brought in the first place,” said Wendy Isaack, LGBT rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. “If the bill before parliament becomes law, it will no doubt intensify abuse against LGBT people.”

The activists said that eight police officers, accompanied by three journalists, forced their way into the conference room, physically assaulted some participants, and confiscated training materials, laptops, and diaries. Several heavily armed members of the Special Weapons and Tactics Unit (SWAT) were waiting outside the hostel for nurses and midwives, where the meeting was held, to assist with the arrests. The activists were taken to the Ho police headquarters, then back to the hostel, where their rooms were searched for “evidence” that they were committing a crime.

A.G., a 25-year-old lesbian, describes the conditions in the cell where she was held with four other women, as being dungeon-like, with no window or light. Activists brought them the only food and drinking water she and fellow inmates received.

“My family did not visit me while I was in the cells,” she says. “I felt suicidal and really wanted to die while I was in there. Even though we are out on bail, I am still having suicidal thoughts because this is far from over.”

The experience of a 24-year-old IT student and equipment technician who was among those arrested highlights the arbitrary nature of the arrests and the dangers of the proposed law, which would make any engagement with LGBT advocacy illegal. He had been hired by the workshop organizers to fix their equipment and was waiting to be paid when the police arrived.

“I tried to explain to the police, but they refused to listen to me,” he says. “I was just at the wrong place at the wrong time.” He remained in detention for 22 days with the others and lost his job as a result.

The Ghanian parliament should ensure that any bill it passes concerning LGBT rights complies with international standards on freedom of expression. It should also reflect the 1993 Supreme Court ruling in New Patriotic Party v. Inspector General of Police that, except in a time of war or when a state of emergency has been declared, no executive agency should suppress the free expression of any opinion, however unpopular. The court said that all Ghanaians, including lesbians and homosexuals, are entitled to freely express their views, to assemble and demonstrate in support of those views and to propagate those views.

For more information, read the full HRW article about Ghana.

Kenya Censors Another Gay-Themed Film

Struggle for LGBT People’s Rights Will Not Be Silenced

By Neela Ghoshal

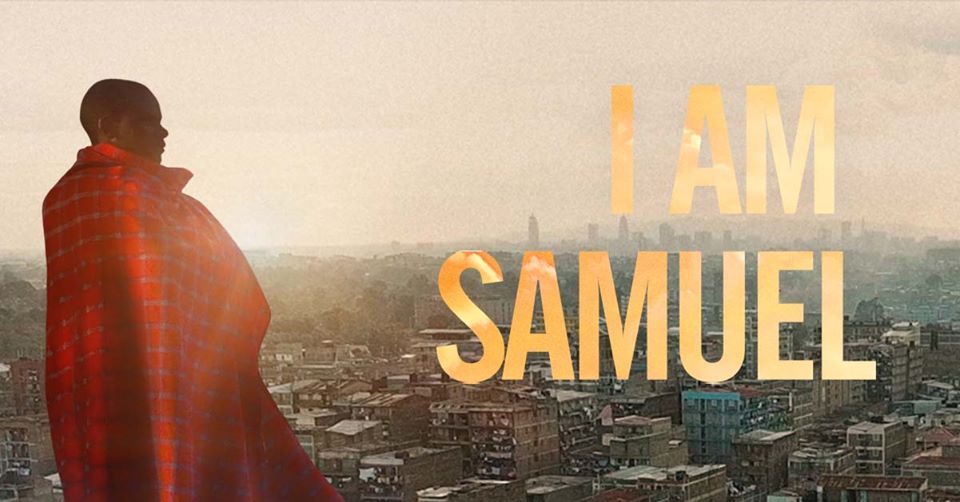

I have never met Samuel, the gay Kenyan protagonist of the acclaimed documentary “I Am Samuel.” But I feel as if I know him. Not only does filmmaker Peter Murimi’s quiet, steady, honest portrayal of Samuel’s daily life create a sense of intimacy and familiarity, but Samuel is the kind of person you know.

Because in spite of discrimination, laws criminalizing their relationships, and the threat of violence, LGBT people in Kenya are ordinary people living ordinary lives. They work as construction workers, like Samuel; as hawkers (street vendors), nurses, accountants, and lawyers. If they live in Nairobi, like Samuel, they visit their families in “shags” (Nairobian slang for rural places of origin), and find both commonality and difference with rural relatives, who struggle to understand aspects of their urbanized lives. If they find love, a community of friends and often family members celebrates and supports them. Life isn’t easy when your government officially designates you a second-class citizen, but daily routines, challenges, and small joys remain, all of which are documented as part of Samuel’s life in Murimi’s film.

On September 23, the Kenya Film Classification Board (KFCB) slapped a ban on “I Am Samuel,” claiming the film contravenes Kenyan values. Which values? During my years living in Kenya, the values I saw in action every day included care and kindness, tolerance, and openness to difference. Kenya is diverse in every way: geographically, ethnically, religiously, and, yes, in terms of sexual orientation and gender identity. For over a decade, LGBT people have publicly staked out their place within Kenya’s vibrant social fabric, challenging discrimination and claiming their rights.

KFCB may want to silence them with flimsy claims that reduce Samuel and his partner Alex’s rich relationship to a “same-sex marriage agenda.” It will not succeed; censorship rarely does. Like the lesbian-themed film “Rafiki,” banned by KFCB in 2018, Samuel’s story will be seen by Kenyans who will make up their own minds. In trying to force on the blinders to deny LGBT people’s existence and rights, KFCB is on the wrong side of history.

For more information, read the full HRW article about Kenya.

Rwanda: Round-Ups Linked to Commonwealth Meeting

Detention, Ill-Treatment of Poor, Gay, and Transgender People

Rwandan authorities rounded up and arbitrarily detained more than a dozen gay and transgender people, sex workers, street children, and others in the months before a planned Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in June 2021, Human Rights Watch says.

They were held in a transit center in the Gikondo neighborhood of the capital Kigali, unofficially called “Kwa Kabuga.” The center is known for its harsh and inhuman conditions, which appear to have deteriorated further due to the increase in the number of detainees and the pandemic. The CHOGM was first scheduled for June 2020, rescheduled for June 2021, and eventually postponed indefinitely in May.

“Rwanda’s strategy to promote Kigali as a hub for meetings and conferences often means continued abuse of the capital’s poorest and most marginalized residents,” says Lewis Mudge, Central Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “As the meeting is rescheduled, Rwanda’s Commonwealth partners have a choice: either speak up for the rights of the victims or be silent as the crackdown is carried out in their name.”

At Gikondo, detainees are held in overcrowded rooms in conditions well below standards required by Rwandan and international law. Former detainees have said they have inadequate food, water, and health care; suffer frequent beatings; and are rarely allowed to leave filthy, overcrowded rooms. People were detained there without basic due process standards. None of the former detainees interviewed were formally charged with any criminal offense and none saw a prosecutor, judge, or lawyer before or during their detention. There were no measures to protect people from Covid-19, and former detainees said they did not have access to testing, soap, masks, or basic hygiene and sanitation amenities.

People interviewed who identified as gay or transgender said that security officials accused them of “not representing Rwandan values.” They said that other detainees beat them because of their clothes and identity. Three other detainees, who were held in the “delinquents’” room at Gikondo, confirmed that fellow detainees and guards more frequently and violently beat people they knew were gay or transgender than others.

In the past, round-ups have been connected to high-profile government events, ahead of which security forces may ramp up efforts to “clear up” Kigali’s streets. Human Rights Watch documented a similar round-up in 2016 before an African Union Summit held in Kigali. Ahead of the now postponed 2021 Commonwealth meeting, several former detainees said the police told them they did not want them on the streets during the event.

Rwanda is one of a few countries in East Africa that does not criminalize consensual same-sex relations. Vagrancy, begging, and sex work are not criminalized either. Yet the authorities continue to use Gikondo Transit Center to imprison people accused of “deviant behavior that is harmful to the public,” including street vending and homelessness.

“Based on past experience, there is every likelihood that similar patterns of abuse will occur ahead of whatever new date is set for the Commonwealth meeting,” Mudge said. “Locking up marginalized people and abusing them simply because the authorities believe they tarnish their country’s image violates human dignity, and Commonwealth leaders should not tolerate this.”

For more information, read the full HRW article about Rwanda.