FAKE: Confronting hatred: Death threats, then an ambush in Kenya

Colin Stewart is a 45-year journalism veteran living in Southern…

THIS ARTICLE WAS BASED ON DOCUMENTS THAT, ON INVESTIGATION, APPEAR TO HAVE BEEN FAKED. It has been labeled “FAKE” rather than simply removed from the blog. As a result, any readers who follow links to it will see the “FAKE” label rather than merely receiving an “Oops! That page can’t be found” error message.

— Colin Stewart, editor/publisher of this blog

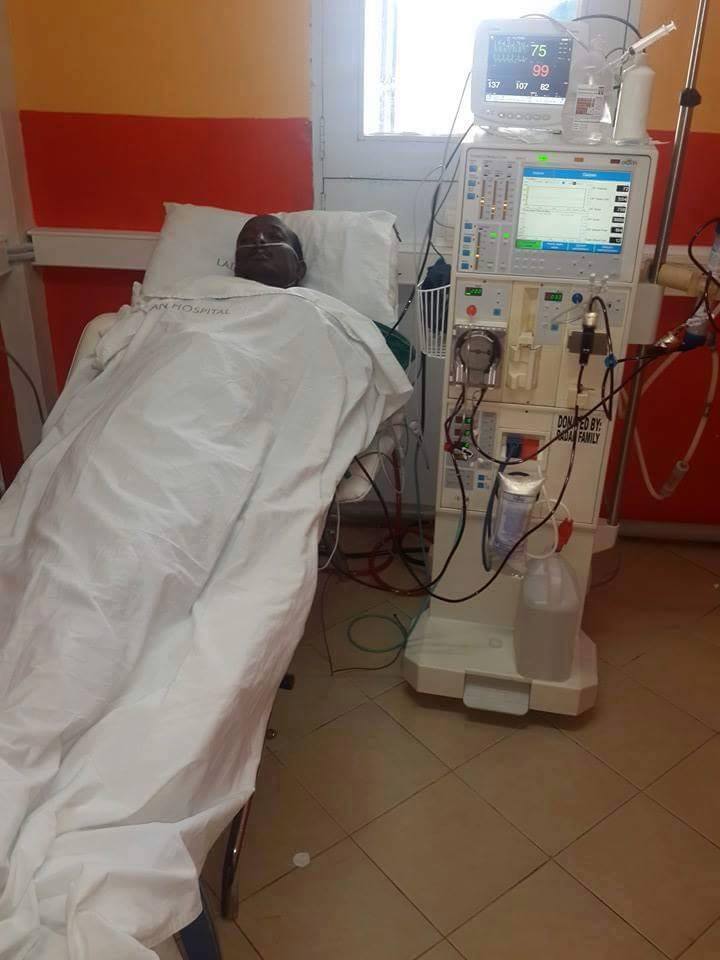

This is the first of several articles about Kenyan LGBTI activist/journalist Joseph Odero, targeted for assassination for his work on behalf of a murdered LGBTI teenager. Despite a nearly fatal attack in January, Odero testified in court about what the murdered youth told him, but now he needs a kidney transplant to survive.

To help pay for that operation, donate to the Joe Odero Fund. Because Odero remains at risk from further attacks, his current location is undisclosed and protective pseudonyms are used throughout this article. Independent verification of the facts of Odero’s case can be arranged, but only by a limited number of people whose involvement would not put his life at risk.

Confronting hatred:

Death threats, then an ambush in Kenya

By Colin Stewart and Joseph Odero

The death threats started arriving almost immediately.

They were all anonymous calls, coming in to Joe Odero’s mobile phone. Not many people knew that phone number, but Joe had given it to police in Malindi, Kenya, two days earlier when he reported the murder of Muhadh Ishmael.

Joe had interviewed Ishmael a few weeks earlier in the Malindi hospital and heard him tell about his uncle, who had arranged for four men to kidnap him in late November. The kidnappers mutilated him and left him bleeding from his groin. Ishmael died of blood loss on Dec. 21. After a post-mortem of Ishmael on Dec. 30, Joe reported the murder to police.

“You fool,” the first caller told Joe. “Drop the case or you will die.”

“Stop supporting the agents of evil. If you don’t, we will do away with you.”

The callers were persistent. Over a two-week period, they made almost two dozen threatening calls, always with the same message. The calls came from about eight men and two women, all from unknown phone numbers. Joe eventually realized he should accept no calls from numbers he did not recognize.

Joe had been threatened before, but not like this. He was an activist for LGBT rights in Kenya, so people had shouted at him before.

Still, Joe thought he was safe. He learned to be careful about which telephone calls he answered and, of course, would never reveal his location to callers.

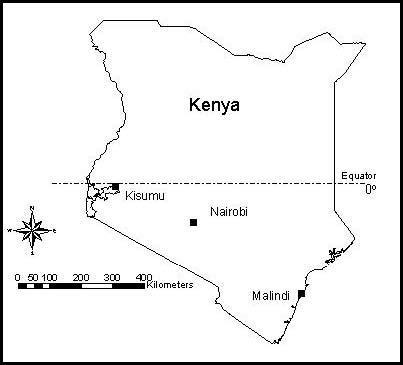

Geography was on his side, since Malindi is on the east coast of Kenya and Joe lived 500 miles away in western Kenya, near the Ugandan border.

He had traveled to Malindi to interview Ishmael for the Erasing 76 Crimes blog, which works with LGBTI rights activists in many of the world’s 76+ countries that have laws against homosexuality. The blog’s editor and publisher, Colin Stewart, was one of the few people who was in contact with Joe about what was going on. The blog had paid for Joe’s transportation eastbound and then back home. Joe informed Colin about the death threats.

In the days and weeks ahead, Joe and Colin became unlikely partners in devising a series of increasingly complex maneuvers to keep Joe safe. Both of them were committed to justice and fair treatment for LGBTI people, but otherwise they were worlds apart — separated by nearly 10,000 miles, connected by the Internet.

Joe, a single gay Kenyan who was living on $60 a month, and Colin, a married, straight, affluent Californian, communicated by internet messages, by email, and a few times by phone across 11 time zones. Joe, age 26, was a novice journalist who worked as an HIV counsellor and advocate for LGBTI rights in the Anglican Church of Kenya. Colin, age 67, was a 40-year veteran journalist who retired from newspaper work in 2011, published the Erasing 76 Crimes blog, and was a member of the Episcopal Church.

That United States-based church, like the Kenyan church, is an offspring of the Church of England, but is despised by many Kenyan Anglicans because it accepts same-sex marriage. The Kenyan church not only rejects gay marriage but also excommunicates any priests whom it suspects of being gay. Joe and Colin first were in contact over Joe’s work as an activist and had worked together on an article for Colin’s blog about a Kenyan street vendor who was kidnapped, raped and burned out of his house because he was gay.

Colin lived with his wife of 45 years in a comfortable three-bedroom Spanish-style condo in Southern California. Joe, the eldest of four orphaned children, lived with his siblings in the Obunga slums in Kisumu, western Kenya, in a one-room corrugated-metal structure on land owned by their grandmother.

At first, after Joe started receiving death threats, that home seemed like a good hiding place. Kisumu is Kenya’s third largest city, with a population of 400,000, so finding one man there should be difficult or impossible, especially in Obunga. But not if your friends tell your enemies where to find you.

It soon became apparent to Joe that not only that people in the Malindi police force were leaking information about him, but so were members of Kenya’s LGBT community, who knew exactly where he lived. From Joe’s witness statement, people at the Malindi police station and courthouse only knew his telephone number and that he lived somewhere in Kisumu. Joe’s enemies knew that information, but they apparently did not have access to technology that could track Joe through his mobile phone. The exact location of Joe’s home should have been a mystery to them.

But on Jan. 16, four men drove directly to Joe’s home without asking for directions. They got out of a dark Subaru and knew exactly which building to approach. By chance, Joe was away from home, but Joe’s 17-year-old brother, Bob, was there. He told them he did not know where Joe was.

The men instructed him: “Warn your brother that he will swallow a bullet through his ears if he doesn’t drop the case — and marry.” They wanted Joe to stop being gay.

They threatened that if Joe could not be found when they returned, Bob and his siblings “would be in for it.” Then they departed.

A little later, when Joe returned home, Bob told him what had happened. Joe immediately left and never went home again.

He slept that night in the pews of a nearby church. He still had his mobile phone, so he used it to contact Colin through an internet message to ask for help. Joe needed bus fare to get out of town. About 25 miles away, he had a friend, Eric, whom he could trust. For safety, Joe also wanted a new telephone and to get rid of the old one, through which Joe was still beseiged with death threats. On Jan. 17, Colin went to the bank, withdrew money and sent it to Joe by Moneygram.

Joe received the money, bought a bus ticket for Kakamega and spent the night at Eric’s place. The next day, he and Colin discussed the situation:

Colin: I hope you think you’re safer in Kakamega than you would be elsewhere in Kenya, don’t you? No one except your friend knows where you are, right? Maybe you can just stay there until the uncle is behind bars?

Joe: Yes, of course. I don’t mind.

Joe decided to seek protection from police because of the death threats and the menacing visit to his home. Police in Malindi had not spurned his report about Ishmael’s death, and some police officers had treated him kindly, so he called there. True, someone on the Malindi police force or in the courthouse had leaked his personal information to his enemies. But Joe would not disclose any further information to them, so the call seemed to pose no risk.

He told Colin about that phone call at about 6:15 p.m. Kenya time.

Joe: I contacted the police in Malindi via phone today. Instructed me to report the threats to my life at Kakamega police station. Am planning to do that today (our time by 8pm)

Colin: Good

The trip to the Kakamega police station did not go as expected.

The sun had set when Joe reached the station at about 8 p.m. Four men were waiting for him in the darkness. They intercepted him before he could enter. One of them said in Swahili, “You fool, you are working as the advocate of the devils.” A second man said simply, “Kill him.” Then they attacked, repeatedly striking Joe in the abdomen with the butt of a rifle. Joe screamed for help from police, but no one answered.

Joe recognized the voice of one of the attackers. It was a voice he had heard on the telephone, threatening to kill him.

One attacker drew a machete and swung it at Joe’s head. Joe fell, unconscious. Across the street from the police station, he lay in a pool of blood with a deep slice in the back of his head.

The attackers left him for dead.

(To be continued …)

Joe Odero needs a kidney transplant to survive the damage done to him in Kakamega. To help pay for that operation, donate to the Joe Odero Fund.

Related articles:

- Intersex in Kenya: Held captive, beaten, hacked. Dead. (Dec. 23, 2015, 76crimes.com)

- Will Kenyan intersex victim get a decent funeral at least? (Dec. 24, 2015, 76crimes.com)

- Intersex victim buried in Kenya; compassion from afar (Jan. 13, 2016, 76crimes.com)

Jamaican official’s appalling criticism of grieving Americans