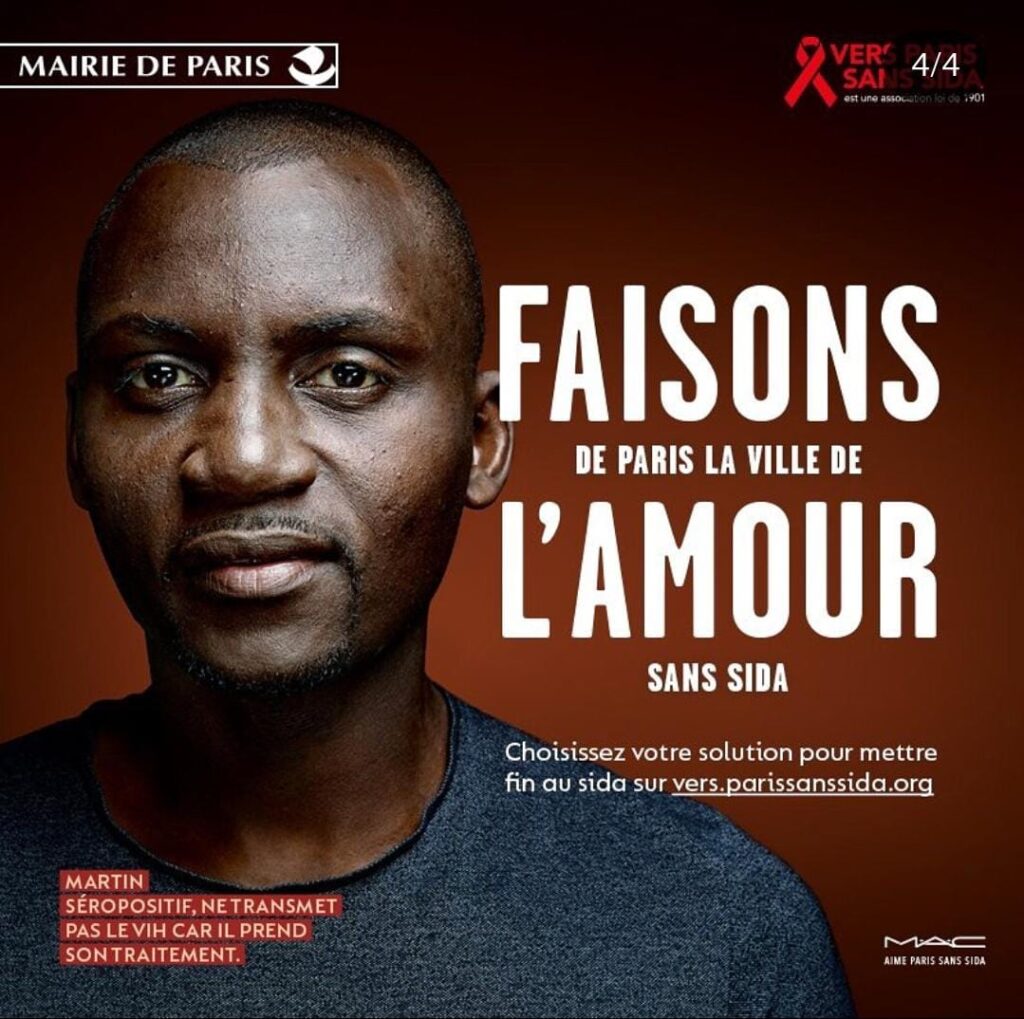

Testimonial: ‘AIDS-free Paris’? I was left without treatment or guidance

Moïse Manoël-Florisse, is an African-Caribbean online journalist keeping an eye…

Bureaucracy as well as racism hinders progress towards an AIDS free world

The ambitious goals of an AIDS-free Caribbean and an AIDS-free Africa are part of the even more ambitious goal of an AIDS-free world. None of those goals can be achieved without eliminating homophobic and HIV-phobic obstacles that sexual minorities face when they seek health care.

Yet even in a less homophobic nation such as France, progress toward that goal still confronts many obstacles. Paris is publicly seeking to become AIDS-free, but the experience of Moïse Manoël-Florisse, our Afro-Caribbean reporter/editor currently living there, shows that much remains to be done.

This is an English translation of his French-language article for the web site of the LGBTQ rights organization Stop Homophobie:

On Saturday, Oct. 14, I went to a sexual health center to obtain post-exposure treatment (PET) after a risky sexual encounter.

Nothing should be more routine for a black bisexual man living in the Ile-de-France who works in the public health and prevention sector, particularly in sexual health. But it wasn’t easy to get access in Paris, and I had to race against the clock to get treatment.

Like many people, I can find myself faced with a risky situation in terms of sexual health: you’re not at home, the configuration of the premises and the way sexual intercourse is going to take place isn’t exactly what you’d hoped for, and you can’t control everything, even when you’re carrying condoms.

Then comes the time of doubt, guilt, remorse and denial, before you decide to tell your story to a professional you can trust, especially if you’re not at all used to this kind of situation.

Sexuality is an intimate space, and it always remains a secret garden over which it’s often difficult to lift a veil of modesty. But while you’re thinking about the right thing to do, the clock starts ticking and you’re faced with two possibilities:

> In a month and a half, I’ll get tested in a laboratory and then I’ll see. The guy seemed “fine”, I’ll believe him and trust him, “don’t overdramatize”.

> I’ve never had to take this treatment, but I’ve heard that it exists, and I’m in a good position to know, since I lead collective “outreach” actions to check and increase young people’s level of knowledge about sexual risks, particularly HIV/AIDS.

In the end, I refused to take the easy way out and wait or put off taking charge of my health until tomorrow, and I can see now that this is not a trivial matter. No matter how many times I’ve tried to start a dialogue about screening with the various people I’ve taken risks with, the answers have almost invariably been the same: “I know what I’m doing”, “I know I’m clean”, “Do you have HIV?”, “Are you sick?”, “Don’t talk to me about that!”

Not reassured by these brief exchanges, eaten away by the weight of regret over my sexual risk-taking, I decided to go to a sexual health center in Paris, also afraid of being shamed in my suburban town in the Val de Marne.

Knowing that I was close to the deadline for post-exposure treatment, I walked hopefully through the doors of the Checkpoint in Paris at 10:00 a.m., a free information, screening and diagnosis center (CEGIDD) dedicated to the LGBT+ community.

I naively explain that it’s been 49 hours since my last exposure, before my interlocutor interrupts me by telling me that it’s already too late in my case and that there’s nothing more we can do.

Cutting the discussion short, he even objected to a legal argument, reminding me that he was only applying the law and that he couldn’t place himself in an illegal situation, and that it would have been possible for me to come a little earlier, if I’d wanted to benefit from post-exposure treatment, under 48 hours in accordance with the interministerial circular of March 13 2008, relating to recommendations for the care of people exposed to a risk of transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

I told him, however, that between 48 hours and 49 hours and 49 hours, there’s only the thickness of a line, and that I doubt it makes much difference to the efficacy of the treatment’s active ingredients. Seeing that my interlocutor was not budging, flabbergasted and outraged, I didn’t make a fuss, keeping my anxiety and indignation to myself.

I’d at least hoped he’d suggest I talk to a psychologist, given the lack of any solution to my stress, but no; it didn’t happen. So I went back to another CeGIDD, knowing that there aren’t many open in Paris on Saturday mornings. Maybe three at most, by my count.

At the Belleville CeGIDD, the welcome was much better. It was explained to me that screening was by appointment, even though the purpose of my visit was different.

A lady then directed me to the nearest referral hospital, and I made my way to the emergency room at Hôpital Tenon, where after a few hours’ wait, I was attended to properly.

There, I was asked if it had been less than 72 hours since my last exposure, which was the case, and I was finally able to benefit from post-exposure treatment, much to my relief.

When I got home at 6 p.m., I was almost in tears, thinking that if I hadn’t taken the initiative to go to another CeGIDD, I’d never have been referred to hospital and would have been left to my own devices without further ado, as it were. I was still in a state of shock.

At the Checkpoint center, at the end of my conversation with the staff, I was offered an appointment for Monday Oct. 16, during my working hours, to get an appointment for the end of the month, in order to have an advanced serology test to find out if I had HIV, but at no point did I feel that they were going to achieve an “AIDS-free Paris”. On the contrary. I was left without treatment or guidance.

Once again, and I’ve spoken to other people involved in the fight against HIV, as well as to colleagues: if I hadn’t been working in the public health sector myself, I probably wouldn’t have benefited from post-exposure treatment, because I wouldn’t have had the tools and resources to cope and get by in the midst of all this. Worse still, perhaps I would have continued to engage in risky practices, misleading myself into thinking that, if such situations arise, there’s nothing we can do about it anyway.

Finally, to this day, I can’t help thinking that this unpleasant situation and refusal of care may have happened to me because I’m a black man. Racism is rampant, and no sphere of society is immune to it. And although I’m not an immigrant, as a West Indian I’m not immune to it either, because of my face.

I’m not unaware that racism can hide behind a zealous application of laws, rules and regulations that makes it difficult to denounce it. However, how can I not express my feelings when I see the gap between my treatment at Tenon Hospital and the lack of a solution provided by Checkpoint?

In the final analysis, my account is part of a broader narrative of the damage done to the health of black people, whether in terms of sexual health, environmental health (chlordecone in the West Indies) or psychological health in the case of police violence, as in the case of Michel Zecler’s traumatic experience.