2022 in worldwide LGBT rights progress – Part 2: Latin America and Caribbean

2022 turned out to be a major year for the advancement of LGBT rights with huge developments in every corner of the world. To celebrate this progress and highlight some of the challenges ahead for the global LGBT community, 76crimes is presenting this six-part series looking at the wins and losses queer people achieved in 2022.

Today, we’ll be looking at Latin America and the Caribbean, where some of 2022’s biggest developments in LGBT rights took place. We saw same-sex marriage become legal in two countries, plus, as discussed yesterday, it became legal nationwide in Mexico. At this point, around 85% of the population of the Western Hemisphere now lives in an equal marriage jurisdiction. As a reminder, many of the countries in the region are parties to the Interamerican Convention on Human Rights and its judicial body, the Interamerican Court of Human Rights (IACHR), which in 2018 found that the Convention assured the right to same-sex marriage. Parties to the treaty are on their own as far as implementing this right, however.

We also saw three countries decriminalize sodomy in 2022, and we’re well on our way to eradicating all laws criminalizing homosexuality from the hemisphere.

Here’s how it all played out in 2022.

This article originally appeared on 76crimes Contributing Editor Rob Salerno’s personal blog.

Earlier in this series – Part 1: North America

Caribbean

DARK BLUE: Same-sex marriage legal.

BLUE: Same-sex civil unions legal.

MAUVE: Certain foreign same-sex marriages recognized.

DARK GREEN: Binding court ruling allowing same-sex marriage, but not yet in effect.

LIGHT GREEN: Country subject to 2018 IACHR ruling for same-sex marriage, but not yet in effect.

RED: Constitution bans same-sex marriage.

YELLOW: Sodomy illegal.

GREY: Sodomy legal, but same-sex marriage not permitted.

Cuba: Following years of campaigning, Cuba became the first independent country in the Caribbean to pass same-sex marriage and adoption into law. The new Family Code also included the right to reproductive treatment for lesbians and single women, and access to altruistic surrogacy. The law was put to a referendum in September, and although some were critical of the referendum process, it passed with a 2/3 majority (with the obvious caveats about the limits of Cuban democracy). Cuba is also the first communist country to pass same-sex marriage.

UK territories: The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC — a body that serves as a sort of Supreme Court for the UK, its territories, and several former colonies) finally delivered its long-awaited rulings in the appeals of same-sex marriage decisions from Bermuda and Cayman Islands, and bluntly, we did not get what we wanted. The frankly baffling decision reversed progress – making Bermuda one of the only places in the world where same-sex marriage went from being legal to illegal. To the Bermuda government’s limited credit, it passed a bill ensuring that already married couples would continue to be recognized as such on the island. The Bermuda opposition has come out firmly in favor of equality, while the government has also ironically used the whole debacle as part of its simmering campaign to build support for independence from Britain (a prospect that is currently not popular on the island).

Meanwhile, the Cayman government remains petulant, continuing to pursue a case to the JCPC hoping to have the governor-imposed civil partnership law overturned.

Over in the Virgin Islands, a case proceeding through the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court is seeking same-sex marriage. In the plaintiff’s favor, the Virgin Islands’ constitution doesn’t define marriage in the same way as the Cayman and Bermuda constitutions do, and the Virgin Islands constitution explicitly bans discrimination based on sexual orientation. Christian groups managed to derail hearings in the fall so who knows when it will finally be heard, but whatever is decided, it’s likely to end up at the JCPC. In late December, the Islands’ premier announced that the government has decided to hold a referendum on same-sex marriage and domestic partnerships. The details of the proposed referendum, including the exact question, whether the proposal is a ban on marriage or limiting the question to Parliament’s discretion, the exact nature of the domestic partnerships, and the proposed date remain unclear at this time (though the Premier has said it will be after the May elections). It will have to be approved by Parliament first, and would be the first referendum in the Islands’ history.

And a UK Lord has proposed a bill that would legalize same-sex marriage in all remaining UK territories, including the aforementioned, as well as Anguilla, Montserrat, and Turks & Caicos. It has not been brought forward for debate, and it should be noted that private members bills — especially those proposed by the House of Lords — rarely become law.

All UK territories are bound by the European Convention on Human Rights to implement at least some form of relationship recognition for same-sex couples, ever since the 2015 ruling in Oliari and Others v. Italy.

DARK BLUE: Same-sex marriage legal.

BLUE: Same-sex civil unions legal.

MAUVE: Certain foreign same-sex marriages recognized.

DARK GREEN: Binding court ruling allowing same-sex marriage, but not yet in effect.

LIGHT GREEN: Country subject to 2018 IACHR ruling for same-sex marriage, but not yet in effect.

RED: Constitution bans same-sex marriage.

YELLOW: Sodomy illegal.

GREY: Sodomy legal, but same-sex marriage not permitted.

Antigua & Barbuda, Saint Kitts & Nevis, and Barbados: All three countries had their sodomy laws struck down by their respective courts this year. Antigua hadn’t even defended the law and has accepted the decision. I have not heard anything about Saint Kitts filing an appeal, which would go to the JCPC. The Antigua ruling goes a bit further than the Saint Kitts ruling; it finds that Antigua’s constitutional prohibition on sex discrimination is also a prohibition on discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. The Barbados judgement was delivered orally in December, with the full written ruling expected in the new year; the government has said it will make its decision after the written judgment is published. If the government appeals, it would go through the Court of Appeal, and possibly to the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) for a final verdict.

This was part of a coordinated campaign seeking to have sodomy laws struck down across the Caribbean region, and I wrote about it more in-depth for Xtra Magazine earlier this year. That article also goes a bit more in-depth on explaining the history and legal structures of the different nations in the Caribbean, which can be a bit confusing.

At press time, we’re waiting on decisions from the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court in sodomy law challenges from Grenada, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent & the Grenadines, and Dominica, which are all expected in the new year. A separate case is winding its way through procedural hurdles in domestic courts in Jamaica, but it could be years before the substantive case is even heard, let alone decided.

Barbados: A same-sex civil union bill has still not materialized, two years after it was promised by Prime Minister Mia Mottley, who was reelected this year with another massive majority. Barbados is unique among former UK territories in that it accepts the compulsory jurisdiction of the IACHR, so the 2018 marriage equality ruling should apply to it if any challenge was brought to its courts. It’s therefore probably the country in the region most likely to get equal marriage next.

Barbados is also in the process of drafting a new, fully republican constitution, and there are efforts afoot to include a nondiscrimination clause that includes LGBT people. Of course, a new constitution could also include new roadblocks on LGBT rights, like a marriage ban or removing/subordinating the IACHR.

In a development that may have been related to the jurisprudence around the striking down of the buggery law, the CCJ ruled that the island’s rape laws covered male victims as well as female victims; the charge of “buggery” is not needed to prosecute a male-on-male rape.

Trinidad & Tobago: The government is appealing the 2018 decision that decriminalized sodomy there, and the appeal is expected to be heard in domestic courts in the early new year. Whoever loses, both sides have said they will appeal all the way to the JCPC. Frankly, I do not think the JCPC will be able to find that Trinidad may continue to criminalize sodomy, given the preponderance of international law on the subject. But then again, I was wrong about the Bermuda case. On a related note, the Privy Council ruled against a plaintiff seeking to have Trinidad’s mandatory death penalty ruled unconstitutional (mandatory death penalties are also going out of fashion worldwide, though there isn’t clear international law on the subject).

All of these territories are former UK colonies, which is why many of them still use the JCPC as their final court of appeal. But that’s changing. Particularly in the wake of the death of Queen Elizabeth II, many of these states are considering cutting legal ties with Britain, including ditching the monarchy and the JCPC. Saint Lucia has begun the process of moving its final court to the Caribbean Court of Justice, which may affect the final decision process in its decriminalization case. (You may be surprised to learn that neither ditching the monarchy nor ditching the JCPC are particularly popular options in the region, and several recent referenda on the JCPC have failed. It seems that many Caribbean people are distrustful of giving more power to the local political class and see the JCPC as a politically neutral body.)

Jamaica: In addition to an ongoing case trying to have sodomy laws struck down in domestic courts, a case seeking the right to same-sex marriage was accepted by the Interamerican Commission on Human Rights in December. The Commission can only make recommendations to a country and is a required step before escalating a petition to the Interamerican Court of Human Rights. Unfortunately, Jamaica does not accept the Court’s jurisdiction, so its opinion will remain advisory only. Curiously, Jamaica is arguing that there is no right to same-sex marriage under the Interamerican Convention on Human Rights, though the Court settled this question in 2018 – there is. The Commission also issued a recommendation last year that Jamaica repeal its sodomy law, but the government has ignored it.

Saint Lucia: While a sodomy law challenge continues, the government quietly expanded the scope of its domestic violence laws to include LGBT people.

Haiti: A new Criminal Code, which had been issued by Presidential decree in 2020, was meant to come into force in June, but was postponed a further two years to June 2024, to give the judicial system and legal profession time to get caught up with its contents. The proposed code established penalties for anti-LGBT hate crimes and discrimination and legalized abortion. The old code had a provision against vagrancy that was often used to target transgender people – I can’t find reports on whether it’s been included in the new code, and the only text of it I can find is an unsearchable 214-page long French PDF.

Aruba, Curacao: In December, the local court for the Dutch territories in the Caribbean ruled that the ban on same-sex marriage in these two states is unconstitutional, and same-sex marriage must be legalized. The effect of the ruling is stayed pending appeal and cassation. Some activists are hopeful that Aruba will not appeal and will simply pass a pending same-sex marriage bill in its Parliament — the bill has been proposed by the junior partner in the governing coalition, but the larger party disagrees with the ruling and some MPs are publicly calling for an appeal and a referendum on the issue. Curacao has announced it will appeal.

The ruling does not immediately apply to Sint-Maarten, the only other Dutch territory were same-sex marriage is not currently legal. But one would have to think if the final cassation ruling is for same-sex marriage, then Sint-Maarten would have to legalize it as well. Appeals should be ruled upon by March.

In the meantime, same-sex couples can still register civil unions in Aruba, and all three islands recognize marriages performed in the Netherlands proper or its Caribbean municipalities (Saba, St. Eustatius, and Bonaire).

Central America

Belize: The government began consultations on a draft new constitution, meant to fully decolonize the country from the UK (the republic question is still open). Among the groups being consulted is the LGBT community, which has enjoyed implied constitutional protection since the 2016 ruling that decriminalized sodomy. The constitution commission is expected to report by the end of next year.

Guatemala: Congress passed a bill explicitly banning same-sex marriage in March, in contravention of the 2018 IACHR ruling. When the president threatened to veto the bill, Congress withdrew it. In November, the President of the Constitutional Court affirmed at a UN hearing that international human rights documents like the Interamerican Convention are supreme over the Guatemalan constitution, possibly indicating a path for marriage equality in the country.

Honduras: The country elected a president who supports same-sex marriage at the same time as it elected a national congress that is very opposed to it. She’s since had to clarify that she will not push it forward, though some of her actions have to be seen as attempts to build support. A Congressman did introduce a bill for same-sex marriage and legal name and gender change for trans people, but it has not advanced. It seems, however, that the President has instructed the government to allow trans people to change legal name and gender in the National Register of Persons anyway.

In January, the Constitutional Court rejected cases seeking equal marriage despite the binding 2018 Interamerican Court ruling. Several cases have been taken directly to the Interamerican Court.

Honduras also joined the UN’s LGBTI Core Group this year, along with Denmark.

El Salvador: The Constitutional Court ruled that transgender people must be allowed to change their legal gender. Meanwhile, the government’s ongoing suspension of civil liberties in a supposed crackdown on organized crime has led to mass arrests of LGBT activists.

Panama: We are now in year seven of waiting for the Supreme Court to rule on its same-sex marriage case, and it seems no amount of brow-beating from activists and lawyers is going to get the Court to publish its decision. I kind of assume that the Court is withholding the opinion because it’s so contrary to public opinion, meaning in favor of same-sex marriage, and it’s worried about public backlash. Certainly if it were a popular opinion, they wouldn’t be holding it back, right?

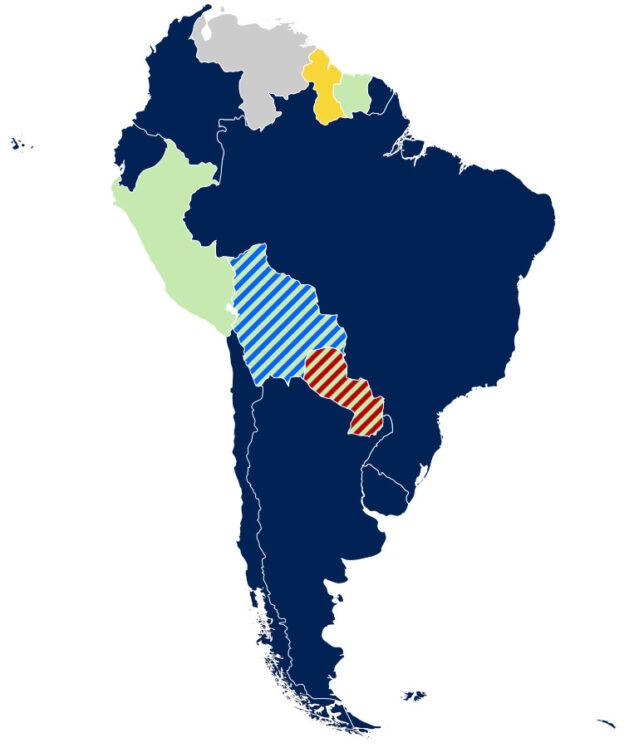

South America

DARK BLUE: Same-sex marriage legal.

BLUE: Same-sex civil unions legal.

GREEN: Country subject to 2018 IACHR ruling for same-sex marriage, but not yet in effect.

RED: Constitution bans same-sex marriage.

YELLOW: Sodomy illegal.

GREY: Sodomy legal, but same-sex marriage not permitted.

Chile: The same-sex marriage and adoption law that was passed last year came into effect in March. Chile’s same-sex marriage law also extends to its Polynesian territory Easter Island, as well as to its disputed territory in Antarctica. Chile was the last of the seven countries with a claim on Antarctica (the others are Argentina, France, UK, Norway, Australia, and New Zealand) to legalize same-sex marriage, so by some measure, same-sex marriage is now legal in every claimed part of the continent.

The government also celebrated the repeal of what it called “the last homophobic law” this year, when it repealed the differential age of consent. The government passed a law banning discrimination based on sex characteristics (intersex status) and a Childhood Law that bans discrimination against children based on LGBT status. Multiple courts also ordered the government to issue nonbinary identification documents.

On the other hand, a proposed constitutional overhaul failed at referendum. The proposed constitution would have included recognition of the right to marriage and freedom from discrimination. It seems the government is pressing ahead with a new process for revising the constitution, however.

Colombia: A court ordered the government to amend the law to allow nonbinary identification certificates, and the government had complied by the end of the year. The Constitutional Court also ruled that same-sex adoptive parents must receive the same parental leave benefits as other parents, and decriminalized abortion up to 24 weeks.

Legislators also introduced a bill to ban “conversion therapy” in the country — actually, they did it twice because the first bill died on procedural grounds. The current bill was introduced in November and is still under consideration.

Venezuela: A nine-day sit-in by LGBT activists led the government to agree to finally implement a court ruling that allows trans people to update their legal gender. The activists had also been demanding equal marriage and a repeal of the ban on gay sex among military members.

Also this year, a minor opposition party introduced a same-sex marriage bill in the National Assembly. Although President Maduro has called for the Assembly to pass an equal marriage law since 2017. A case seeking same-sex marriage has been pending at the Supreme Court since 2015. It is unclear if the country is under the jurisdiction of the IACHR, but it probably is not for all effective purposes. Former President Chavez withdrew from the Convention in 2013; the opposition-controlled National Assembly rejoined it in 2019, but that Assembly didn’t have effective rule over the country.

Suriname: The courts ruled that the state must allow trans people to update their legal gender. The country is subject to the 2018 IACHR ruling, but no action has been taken to implement it, nor has a case been brought to the courts. Perhaps this former Dutch colony will be influenced by the Aruba and Curacao case after it’s resolved in the new year.

Guyana: Guyana appears to be the only country in the Western Hemisphere that has a sodomy law that is not currently subject to a court challenge, but presumably regional activists have it in their sights once the cases in the Eastern Caribbean islands are complete. Or maybe the government will see the writing on the wall after all the other former British colonies have their sodomy laws struck and it’ll repeal it on its own. Meanwhile, the government launched an initiative this summer to promote the Rupununi district as an LGBT tourism destination in coordination with the local LGBT rights organization SASOD.

In December, the Court of Appeal ruled that the death penalty is not unconstitutional.

Brazil: The homophobic president Bolsonaro lost his reelection bid, while two LGBT people were elected as state governors.

Peru: The Constitutional Court delivered a truly bonkers ruling against same-sex marriage, finding not only that the ban was legal, but that Peru was not bound by the 2018 Interamerican Court of Human Rights ruling, because (essentially) they didn’t agree with it. Meanwhile, legislative attempts to pass equal marriage hit a stone wall, as conservatives hold power in the state congress.

In December, homophobic but leftist President Castillo was impeached and pushed out of office by the Congress after he attempted to dissolve congress in a power grab. His own supporters accuse the conservative-led Congress of its own power grab and protests led to many deaths. The new President has agree to move forward new elections to April 2024, but the situation remains volatile.

Bolivia: The ministry of justice has said several times over a couple of years that it is expecting a ruling from the constitutional court regarding same-sex marriage, but 2022 seems to have gone by without one. The state ombudsman’s office also called on the government to fully recognize same-sex couples and families and trans gender identities in accordance with the 2018 IACHR ruling.

The legal situation in Bolivia is complicated: the constitution defines marriage as pertaining to opposite-sex couples, but the constitution also says that the IACHR takes precedence over it. So the 2018 ruling should prevail, as it did in Ecuador in 2019.

In the meantime, at least four same-sex couples have managed to register a “free union,” which entails all the rights of marriage.

Paraguay: The government passed a law banning medical treatment of sexual orientation as a disease.

Argentina: Although the country was a leader in passing same-sex marriage in 2010, it’s lagged behind in recent years. Pride marchers called for a broad anti-discrimination law, and a law for legal gender change. Also, despite a ban on medical workers performing “conversion therapy,” it emerged that the practice was continuing in the country with little effective control.

Tomorrow, we’ll take a look at Africa and Oceania.

This will be an interesting stock take on progress nonetheless, because the mere idea of challenging the anti-LGBTQ laws and by-laws signals a certain nuance to activism in mostly the global South and sub-Saharan Afrika in particular.