Chechnya: Islam + tribal honor = danger for gays

Colin Stewart is a 45-year journalism veteran living in Southern…

In Chechnya, traditional leaders feel threatened by society’s free access to information online, by empowered and independent women, and by the very existence of queer people.

Ekaterina Petrova, a Russian lesbian activist, takes a look at the historical and social background of Chechnya’s brutal purge of its LGBT citizens. This article is published here courtesy of ILGA, the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association:

Banishing devils: Chechen authorities against laws of life?

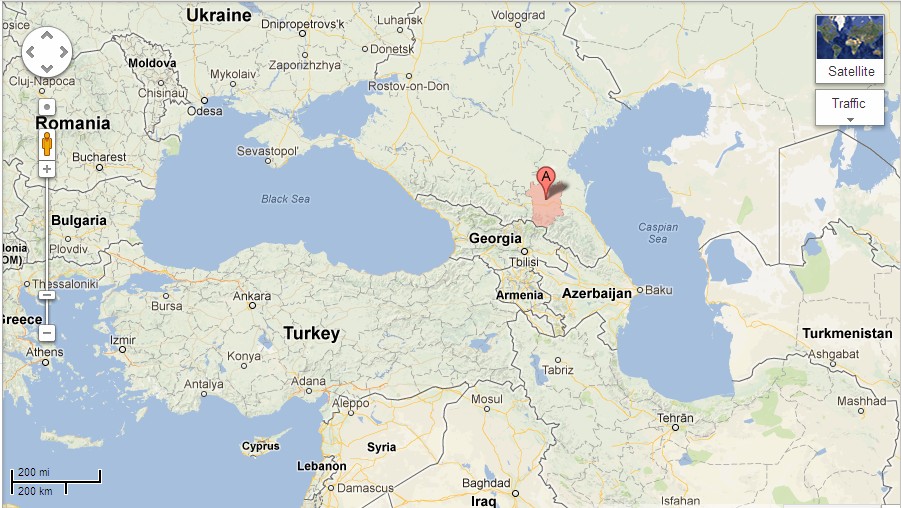

The complex and challenging situation with human rights in the North Caucasus region has been attracting the attention of international organisations for some time, particularly in relation to the stark news of brutality directed against LGBT people in Chechnya in 2017 and 2018.

There are seven republics in the region: Adygeya, Ingushetia, Dagestan, Kabardino-Balkariya, Karachai-Cherkesia, North Ossetia, Chechnya, and within each of them varying levels of nationalistic and religious influences. In recent years, the political situation in Russia, and particularly Chechnya, has empowered conservative and fundamentalist forces across all aspects of society.

A 2016 report (draft resolution) of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe alerted the Council of Europe that despite the Russian delegation’s acceptance and agreement to the 2010 Resolution 1738,64 impediments and delays in implementation continue, effectively denying “human rights and rule of law” in the region. Specifically, terrorism, impunity of officials, access to justice, non-performance on ECHR decisions, and the vulnerability of human rights NGOs were identified. The Rapporteur also noted that his attempts to visit the region had been actively frustrated by Russian authorities.

The two reports quoted above (2010 and 2016) remark on the implementation and effect of the strict dress code in place in Chechnya, noting threats and violence towards women who break it.

A joint shadow report discussed by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) in 2015, identified setting of religious rules for women and girls dress codes, marriage and family discrimination, gender-based violence —including marriage of underage girls, female circumcision— and so-called “honor killings” as issues of major concern.65 Also in 2015, research entitled “Life and the Status of Women in the North Caucasus”, based on interviews in Chechnya, Ingushetiya, Cabardino-Balkariya and Dagestan, illustrated the lived effects of family budget pressure, limitation of movements because of traditions, and domestic violence.

Prior to early 2017, very little was known or written about LGBT people’s lives in North Caucasus region, including by Russian SOGI-related groups, although there had been some reports of transgender individuals fleeing family and police violence and death threats. At the end of March 2017 information about extensive torture and killings of gay men in Chechnya became known.

However, it was not until the end of 2017 when the first reports of detentions of lesbian and bisexual women and girls became known, amidst fears that police had lists of women’s names, and also their social media identities.

Other than Adygeya and North Ossetia, the predominant religion in other republics is interpretative of Islam. In addition to the Sharia law, the influence of traditional ‘adat’ tribal code of conduct and conflict resolution between individuals, communities, and tribes remains strong. Across the Northern Caucasus, the ‘adat’ held that the ‘Teip’ was the chief reference for loyalty, honour, shame and collective responsibility. ‘Adat’ set norms according to traditional standards, such as ‘honour killings’, blood feuds, bride abductions and the persecution and killing of LGBT people a ‘washing away the shame’ that the victims have brought to their ‘tribe’.

In modern Chechnya the concept of the ‘tribe’ is deeply ingrained: regarding the ‘shame’ generated by a family member being known or perceived to be gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender, both authorities and local society apply pressure on family to punish them. State authorities have also denied the existence of LGBT people by saying ‘such’ people would be killed very fast, and the people claiming refugee status must not be Chechen. The rhetoric of national moral superiority pervading the Chechen political space, helps explain why political and spiritual leaders deny the very existence of sexual or gender diversity in Chechnya.

It is a further twist that the people who commit ‘honour killings’, as reported, often consider themselves as “victims of the situation”, forced to carry out the act: they love their family member, but they feel they have no other choice when the person “crossed the line” and “become a gay, lesbian, bisexual and/or transgender”. To allow the entire family live “properly”’, the family feels it must purge or “wash away the shame” to allow the family resume normality. There are recorded cases of family members trying to help their LGBT relatives escape, at their own personal risk.

Currently, Chechnya is presenting as the most dangerous for LGBT-identified or LGBT-perceived people among the Caucasian republics. The legacies of two recent wars have resulted in widespread weapon/gun-ownership high levels of PTSD (posttraumatic stress disorder) amongst the general public, and high levels and aptitude for violence.

Further, during and after the wars, socially and politically radical interpretations of Islam came into the republic with Middle East missionaries.

What has been described here is a situation whereby a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity is not considered a private matter but has implications for their families and wider community. The social institution of the family in the North Caucasus region includes the extended family and the “shame” generated by deviations may result in the family’s exclusion from social communications and events, and where people will avoid marrying members of this family. “Honour killing” help to repair a family’s reputation and are generally carried out by the male members of families. However, “honour killings” pose significant challenges to later investigation: they may have been organised as an accident, a disappearance or a poisoning. Relatives and neighbours rarely voluntarily come forward as witnesses. There are particular silences around “honour killings” of LGBT people. It is understood that the executor thinks that his efforts will be rewarded after his death.

Before a killing, relatives reportedly often try to change their LGBT family member through various forms of violence: beatings, placement under house arrest for months or years, and imposed isolation through removal of all communication devices. A version of “conversion therapy” is also prevalent — the “djinn expulsion”— a form of exorcism found commonly in society and in some mosques. The procedure variously includes physical restraint, and high-volume reading of the Koran through screaming in the ears of the person or headphones.

The exorcist speaks to the bad spirit or “djinn”, asking about its location in the body, the way it entered into a person, about its desires. Then the exorcist persuades “djinn” to escape the body, through threatening him. To make the ‘djinn’ exit the body will often require physical pressure of the body part where the “djinn” allegedly resides. In some mosques, it is the mullah who decides whether a “djinn” exists, but if none is detected the outcome may be worse because this may be interpreted that the person has consciously chosen their non-traditional sexual behaviour, and therefore seeks and deserves death.

International and Russian human rights activists report that the situation in the North Caucasus, especially Chechnya, is critical. But it must be noted that the conservative part of North Caucasus society does not agree: they are disgusted by several new trends: unfiltered access to information has increased, women have become more empowered and independent (increasing numbers of women are initiating divorces and refusing to marry a second time), and a social conversation about the existence of queer people has even begun. SOGI issues are a largely marginal topic for the North Caucasus, but these issues have quietly begun to be spoken out loud. Like so many other parts of the world until a problem is stated aloud, it ‘does not exist’.

Ekaterina Petrova, the author of this article, is a feminist and lesbian activist from Saint Petersburg, Russia. She worked with Chechen refugees who were victims of the anti-LGBT campaign there.

lol, you make it sound as though ‘tribal honor’ isn’t part of Islam