A priest’s 40-year journey toward gay liberation

‘Whose service is perfect freedom’

A queer priest reflects on his 40-year journey toward gay liberation

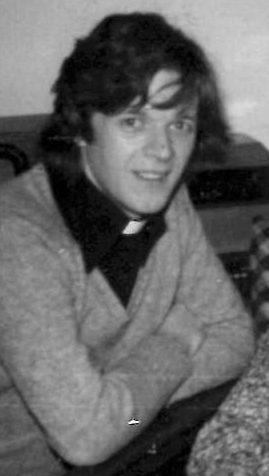

A sermon on July 2, 2017, celebrating the 40th anniversary of his ordination

By the Rev. Albert Ogle

The Anglican Book of Common Prayer reminds us that true freedom cannot be fully claimed until we understand its connection to serving our fellow human beings. It’s a paradox. Freedom is not ours to do what we want. That may come as a disappointing shock to some, especially on this 4th of July where liberty and freedom are wrapped in flags of nationalism or simply wafts of sentimental religious piety. Americans have been trained to celebrate freedom annually with colored controlled explosions in the sky that sometimes produce audible expressions of awe. Here is a moment where religion can surprisingly liberate us from a culture that has hijacked and domesticated the concept of freedom. Our ability to be truly free, is also connected to the freedom and liberation of others and to seek and serve this wider and nobler vision. I found this ancient prayer helpful:

“O God, who art the author of peace and lover of concord, in knowledge of whom standeth our eternal life, whose service is perfect freedom: Defend us, thy humble servants, in all assaults of our enemies; that we, surely trusting in thy defense, may not fear the power of any adversaries; through the might of Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.”

Protection from enemies means something different to a transgender teenager or an activist in Uganda perhaps than the vision of the author of this ancient prayer. However, the prayer speaks to a common deeper vulnerable longing for a fruitful and love-filled life. What does freedom mean to you?

This past week, I celebrated a remarkable journey in my quest for this true freedom. Religious leaders in every faith tradition share a common function – we mark TIME for people. We are there when a family welcomes a new member at birth, when a human being crosses the great divides between childhood and adulthood and life and death. We celebrate moments of new beginnings and blessing relationships like marriages. So in marking time for people, religious leaders help us make sense of life’s complicated and sometimes cruel journey. Time is not meaningless -it is sacred and it is in this time that we learn to love what God is making in us and what we can contribute to the greater whole, for the short time we are all here. This week, in celebrating 40 years in the ordained ministry of the church as an openly gay man, I was forced to think more intentionally about my own “markings” on this amazing yet difficult journey.

When I was ordained in Ireland in 1977, our religious civil war was at its height. Terrorists were blowing up innocent parents and children in Belfast restaurants. The British government was interning suspected terrorists (and many innocent people) without trial or due legal process. It was still illegal to be LGBT in Ireland until 1982 and the only significant thing Protestants and Catholics agreed to fight together was to oppose any move to change the anti-gay laws that remained on Ireland’s books, even though the mainland United Kingdom had repealed them. The churches were all complicit in this oppression.

To consider ordination in the Anglican Church in Ireland back then, as I was discovering that I was a gay man, in love with another man, was sheer madness. It was inconceivable to me that I could become a priest and be gay, but it was God that had planted this idea in my limited imagination. Lots of people around me (who presumably had no idea I might be gay) also encouraged me to take the steps needed for ordination. Three years at university and two postgraduate years at seminary and a teaching credential tucked away as an insurance policy against being exposed and fired a s a priest. At least I would have a job when I got kicked out of the church. It was smart to think ahead and the teaching credential actually came in very useful when I was fired three years into my ministry.

I am now happily married to another man and our congregation in St. Peter’s Lithgow (in Upstate New York) love us both dearly. What was unimaginable 40 years ago, is now simply a non-issue. The parish called us to be with them three years ago. It was not what we expected and another one of those surprising turns in the road as we moved home from one coast to another.

Within my first year as Vicar here, an older lesbian couple came to me and wanted to be married in church. We had a beautiful service in our old wooden church and although it was the first ever same gender marriage, no-one around here blinked an eyelid. I didn’t have to get permission from the bishop or my Vestry (Board). It was just like every other wedding and the normalcy of it all actually upset the couple because they wanted much more “hoopla” and headlines, but this was simply what St. Peter’s was now doing. They would treat LGBT folk in the same way as they had done with straight couples for centuries.

This normalcy was shocking and even disappointing to the couple who wrote me a long letter and were so upset they felt they needed to leave the parish. I thought, “How sad!” In all the ups and downs of ministry, I never expected something like this and for weeks, I just had this heavy stone in my stomach and could not figure out what had happened to upset these dear people. Here was a community that was fully embracing and supportive of their love and journey and the couple had simply missed the moment.

When we are no longer victimized

They eventually came around, but it was an interesting reminder that when we are no longer victimized, it is us who need to change our attitude and I was reminded that changing laws and attitudes does not necessarily bring a sense of freedom that we may expect. Sadly, there are lots of people who simply thrive on victimhood and their whole identity is based upon being “other”. How do we deal with change when we are no longer victims? Change is hard work and demands WE change. This change in the west is also a threat to many in the developing world.

Yet, the new world order I am describing (through a lens of Western secular liberal culture where religion is still dominated by traditional values) is seen as a threat, particularly in developing countries and their vast unquestioned religious industries.

We live in an age where fundamentalism, in its many forms, is a global business. It fuels ISIS as much as its grip helped to clinch the billions of dollars of arms deals between American and Saudi Arabia. Fundamentalism fuels the evangelical American prosperity gospel that has deep pockets in USAID paybacks for Presidential and party loyalty and makes it difficult for African LGBTI people to even think about the kind of societies they want to shape. These industries have much to lose if fundamentalism wanes. The cost of this madness is an unimaginable waste of gifts and human potential. It is like millions of stillborn vocations where people who are wanting to contribute to the well-being of the societies and support their families, simply cannot. It is as much a vocational issue as a human rights issue. Lost potential. A calling but the community who might benefit is deaf and unable to hear or see our contribution.

I too had a calling that seemed to be unheard, unaffirmed and even thwarted. I never thought I could do it or society would allow me to do it. As I reflect on 40 years of progress where I can now function openly as a married gay priest and serve everyone in my community (even though at times it may be too much to bear on all sides including lesbian neighbors), it may take people now in their teens and twenties yet another 40 years to develop and mark their own unique journeys to freedom through service.

We need to mark these steps on the journey as I have done this week for my own sanity and orientation. Where the hell am I? All the fighting, rejection, the stabbing in the backs, the internalized homophobia and racism in our own communities, while trying to minister to street kids kicked out by their fundamentalist mid-western and suburban parents in the 1980’s. How is faith formed cleaning up shit as a person with AIDS is dying one day? Then, as a priest, you sit on a dying person’s bedside and tie your priest’s stole around his skeleton-like emaciated hand with their partner who will soon be a widower? How can I not affirm this love and desire?

Love and sacrifice..I have seen it in many forms during this remarkable journey. These pretty symbols woven into my pure white clergy stole -a red ribbon, a pink triangle and gold spirals representing my home Irish church community that spiraled me towards the future by kicking me out — all these pretty symbols hide deeper conversations and tales that are easy to forget when it is simply so easy to witness a gay marriage today, or even a 40th anniversary of being a priest. There are not many of us who have been allowed into the priesthood for so long.

As I reflect again on these pretty symbols, they can become like war medals. Best simply worn undisclosed and without commentary. They remind the bearer of the faces and smiles and loyalty of fallen comrades and ferocious advocates who passed the torch to the next generations. We who survived become reluctant messengers of a story no-one wants to hear as the newly liberated modern gay couple celebrate the design of our sleek kitchens and pick out fabulous countertops.

Abraham and Sarah

Like the spiritual journey of some ancient Hebrew couple called Abraham and Sarah who left home, seeking a place to belong and settle, I can perhaps relate today more fully to their story and claim that I am as much a part of the human family as anyone else. All three great monotheist religions share Abraham and Sarah as our spiritual ancestors. It is radical to claim, even in this day and age, that I too am a child of Abraham.

My secular friends shrug their shoulders and have no idea who Abraham and Sarah are, dismissing religion as passé and unhelpful to the struggle for liberation. Meanwhile the churches in Ireland dismiss my claim that I am a son of Abraham or a follower of Jesus, and some may even deny that I am a real priest.

That’s the point. I claim I have as much a right to being here and being part of this story as they claim. In some cases, I know this biblical story better than they do. While we disagree (thousands of people took to the streets of my home city Belfast this week, claiming the same rights to marriage equality as in other parts of the United Kingdom while the churches in Ireland man the barricades against them), ISIS simply pushes another queer off a rooftop to swing from a rope held high by a crane. These lifeless corpses have no claim to be children of Abraham and Sarah and how dare we even claim to know this story. We are part of a much older and bigger story. I tried to weave my story and journey with Abraham and Sarah’s yesterday as I remembered the past 40 years. So many didn’t make it.

I have two hopes from this sermon. One, that places where there appears to be little hope of change..these dark places on the road (I describe them as forks in the road where it looks as if we must choose to lose what we seem to love most and sacrifice all we know and love about who we are epitomized in the story of Abraham sacrificing his son Isaac) — these places will not appear so frightening to LGBT people as we move through the darkness and despair into the clarity, light and freedom.

Gay liberation that has largely been presented in western terms over the last 50 years around the Stonewall mythology is not the freedom I am describing either. We have pink-washed American consumerism fornicating with an American rugged individualism and the offspring of this illicit relationship is the illusion of 21st century gay liberation. It is a dangerous illusion and many of us in the West who are critical of the evangelical exportation of prosperity gospel/family values bullshit that Africa and South America seems to believe (300,000 Prosperity Gospel churches in Africa alone, paying Rick Warren’s salary through sales of his prosperity gospel heresies).

Yet, we are as guilty as exporting a false gospel to Africa, in this gay liberation package that is not sustainable in Africa or anywhere else. It is not about true freedom. I think this is where religious and secular gay liberationists disagree on the future of our movement, especially in the larger developing communities at this critically dark fork in the road.

As Trump turns off all the American funding supporting the gay human rights activist industry, a different kind of faith and value system will fill the vacuum. African, Asian and South American leadership in the LGBTI communities should not see this as a negative problem but an opportunity to move forward into a different paradigm and movement than say in the past decade.

The second thing I hope for on this 40th anniversary of my journey is that secular organizations in the LGBTI movement will recognize the contribution religion and religious leaders have had on our journey to true freedom and make room for us and others at the table. I am amazed how religio-xenophobic the Western LGBT movement has become in such a short time and the contribution of individuals and organizations in the religious sector is still undervalued and denied.

One recent example comes to mind when I joined a conference call organized by The Williams Institute, based in Los Angeles. The conference call was themed “The Place of LGBTI folk in the Sustainable Development Goals.” A Swedish researcher presented a background on how this internationally agreed agenda might include us. It was a well thought out presentation and, as I have been following this strategy here in New York through the work of many NGO’s at the United Nations, I was familiar with most of the information.

Not once in the presentation was the role of religious leaders or organizations mentioned. In places like Africa, where 40% of healthcare development is provided by religious networks and driven by powerful religious values, many of which are good and inclusive, how could a respected academic body like the Williams Institute allow for such oversight?

Not everyone is so blind. I respected Bryan Choong coming all the way from Singapore in 2012 when St Paul’s Foundation and other faith-based organizations invited 26 activists to be part of the International AIDS Conference in Washington DC. Bryan admitted to the selection committee that he did not share in any faith tradition but he came to be among us to learn more about the role religion can play in shaping public policy and mobilizing people.

We selected him to be able to come, because he knew religion plays so much, even in opposition to our movements, and he wanted to expand his knowledge and understanding of how to deal with this as a reality, both as a positive force for good, and a way of understanding all assaults of our enemies. When my angry lesbian couple I cited earlier (who were recently married by me, an ordained Anglican priest in a very conservative Republican stronghold and traditional Episcopal church) realized that for 30 years, our issue had been debated and fought over by 3 million Episcopalians, eventually ending in a very negative and financially costly divorce and split in our churches, their understanding changed.

They realized how much OUR issue has cost the church who now stand with us. To take a stand for our freedom demanded enormous sacrifice and struggle and commitment from countless straight allies. It was a very ugly and hard-fought battle, so that my wonderful lesbian couple could simply walk arm and arm up the aisle of St. Peter’s church in Lithgow and no-one batted an eyelid. This is simply what we now do.

Next, is there a place at the table for this kind of advocacy and normalcy? I realize after reflection on my own journey this week, that St Peter’s represents a place of hope and light to churches and countries still dominated by religious fundamentalism, as we see in places like Northern Ireland and Uganda.

Things change and the change is dependent upon people simply showing up and showing what they want to contribute to the greater whole..service to benefit the whole society, not just the rainbow piece of it. The downfall of any movement comes about when we forget our own story and through his collective amnesia, we then begin to believe our own bullshit.

This is an interesting and dark fork in the road for our movement — a movement that I and many religious LGBTI people and our ally friends helped to create. We have a responsibility to communicate more clearly what that was like for us and trust those who take up the mantles and stoles of the future to accept the things they can change, wisely, recognize the things they will not be able to change (but others undoubtedly will) and have the wisdom to know the difference.