HIV services cut back in America’s new global health strategy

Colin Stewart is a 45-year journalism veteran living in Southern…

Trump administration has drastically reduced funding for HIV services in developing countries

As the Trump Administration looks to the future of the worldwide fight against AIDS and other diseases, it plans more budget cuts, but also promises to adopt a new approach that will require nations to restructure local health initiatives in order to receive American aid.

The “America First Global Health Strategy,” unveiled last month, also calls for:

- Continuing to strive to achieve global targets aimed toward ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.

- Demanding that other nations take more ownership of health programs within their borders.

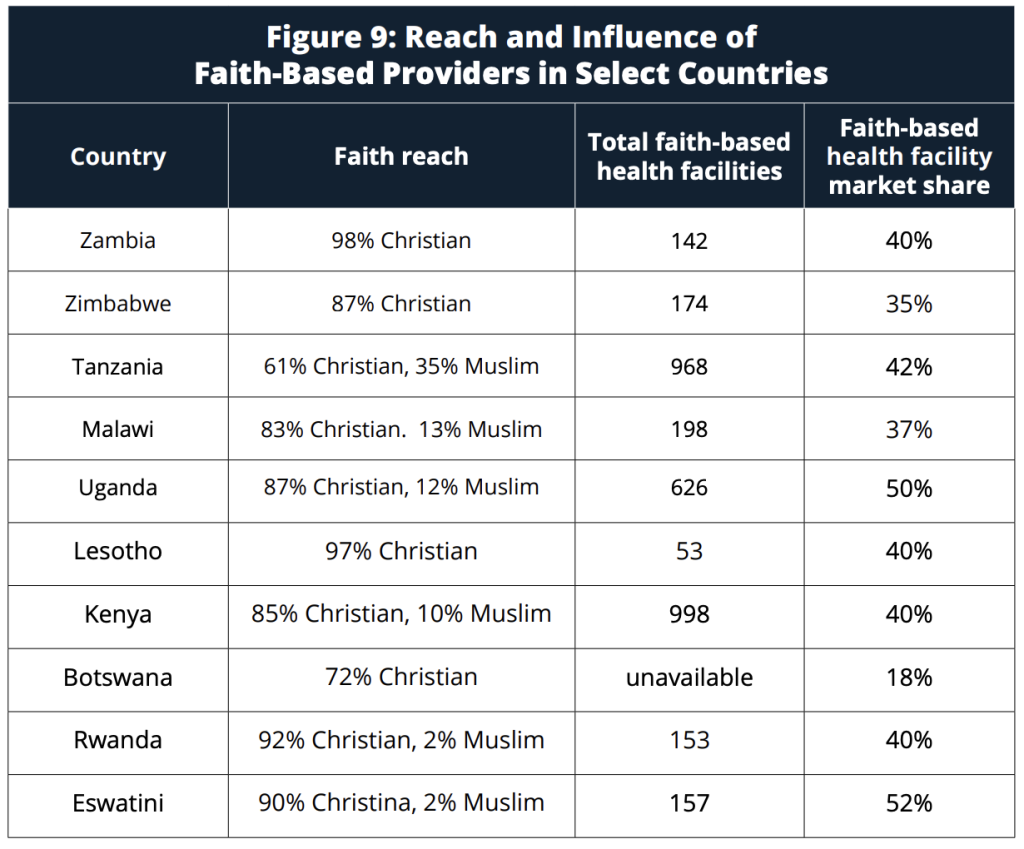

- Integrating HIV services into local health systems, including faith-based organizations. For members of the LGBTQ community, that can be a problem in the many nations where those organizations are homophobic.

- Reducing reliance on independent agencies serving multiple nations.

- Reducing agencies’ funding for technical assistance, shifting that task to local governments.

- Reducing agencies’ funding for monitoring program quality, again shifting that work to local governments.

- Using American single-nation grants to counteract the influence of Chinese lending.

- Assigning health staff to each U.S. embassy to monitor disease outbreaks that might threaten the United States.

The Devex news agency analyzed the new U.S. global health strategy in an article that has been edited, shortened and reprinted below.

How will America’s new global health strategy change PEPFAR?

The global AIDS community has been awaiting a plan from the Trump administration beyond funding cuts. But the “America First Global Health Strategy” released last month, is not what many were hoping for.

While it prioritizes sector goals, such as greater country ownership, it would also withdraw funding for technical assistance or to monitor program quality. Experts say these pieces have been crucial to the success of the flagship U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, which is credited with saving 26 million lives since its launch in 2003.

By eliminating that support — along with swaths of prevention and community-based initiatives — experts warn that the Trump administration is undermining PEPFAR’s lifesaving capacity.

“This is not PEPFAR,” Nina Schwalbe, the CEO and founder at Spark Street Advisors, told Devex. “It’s something else.”

Until the release of the new global health strategy, the Trump administration had largely been focused on shrinking U.S. support for the global AIDS response. Since taking office nine months ago, officials have dismantled the U.S. Agency for International Development, which implemented the majority of PEPFAR’s programs, and eliminated PEPFAR contracts.

That includes about 65% of USAID’s PEPFAR awards, which account for 24% of the funding the program was supposed to spend, according to Ramona Godbole’s analysis for the Center for Global Development.

U.S. officials have pledged to maintain support for lifesaving services. For the AIDS response, that includes HIV testing and treatment and services to prevent mothers from transmitting HIV to their newborns. However, Godbole found that 16% of the programs that met this definition of lifesaving were eliminated in the USAID awards that have been terminated.

At the same time, Trump officials attempted to rescind $400 million that lawmakers had allocated to PEPFAR. After that attempt failed, officials withheld some of that money. And the Trump administration has requested $2.9 billion for PEPFAR in the 2026 budget, which would be a $1.9 billion decrease from the previous year’s allocation.

Now comes the “America First Global Health Strategy,” which offers more than just cuts.

It signals an intent to extend — at least temporarily — the administration’s commitment to lifesaving services and to expand support for some additional prevention efforts, including lenacapavir, a six-month injectable that offers near-complete protection against HIV infection.

The strategy also alludes to America’s commitment to achieving the 95-95-95 targets established by the Joint United Nations Programme on AIDS, or UNAIDS, as crucial steps to ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030. The targets call for 95% of people living with HIV to know their status, 95% of those to be on treatment, and then 95% of people on treatment to have their virus suppressed by the end of this year.

UNAIDS welcomed the strategy, calling it a “timely initiative” that “underscores the continued support of the American people and the U.S. Government in the historic effort to end AIDS.”

How America will extend this support, though, is changing. Rather than PEPFAR’s longstanding approach of funding NGOs to implement and oversee programs, the Trump administration plans to finance governments directly, while also leveraging support from the private sector and faith-based organizations.

Schwalbe called this a “bit of a bait and switch,” given that private sector operators and faith-based NGOs were already implementing PEPFAR programs. The State Department, which administers PEPFAR, did not respond to a request for comment.

The U.S. commitments would be laid out in bilateral memoranda of understanding that require coinvestments from domestic governments alongside benchmarks to unlock future American funding.

The idea is that increasing local investments will lead to sustainability, while encouraging governments to integrate HIV services into local health systems.

“Long-term sustainability, country ownership is something we have been working towards in PEPFAR and broader global health spaces for many years,” Godbole told Devex.

Washington wants multiyear bilateral agreements in place for most of the 71 countries it supports by the end of 2025. And according to the strategy, they should “include a full transition to country self-reliance over the timeframe of the agreement.”

Godbole cautioned, though, that this timeline may be too rushed to accomplish a meaningful transition. She also joined experts who have expressed concern about what the strategy will not support.

While the administration commits to continue funding commodities, including HIV treatment, and front-line health care workers “who directly deliver services to patients,” it would draw down support for other elements of PEPFAR that it largely dismisses as “overhead costs.” These include training, quality management, and technical assistance programs.

“I’m concerned that the strategy sets up this false dichotomy between commodities, health care worker salaries as good investments versus everything else lumped into this nebulous overhead,” Godbole told Devex.

The reductions threaten to undermine the very achievements that the strategy celebrates, Emily Bass, the author of a book on the history of PEPFAR, told Devex.

“It’s a fascinating conclusion to come to, that a program that has achieved so much of what it set out to do and delivered results in countries based on a set of approaches that was comprehensive can be recognized for its achievements and then also scaled back to two components of that multi-component investment going forward,” she said.

This is alongside the elimination of support for tailored services for marginalized populations and prevention efforts beyond lenacapavir for pregnant women. The administration suspended support for these programs when it froze foreign aid in late January and has subsequently eliminated many of these projects. The new strategy does not mention any plans to revive them.

The plan also seems to contradict some of the actions that the Trump administration has taken. While it groups community health workers, or CHWs, among the front-line health workers that it seeks to preserve, U.S. officials have cut CHW programs across sub-Saharan Africa. While some of those programs don’t directly deliver treatment or prevention, they do recruit people into HIV programs and raise awareness about services in communities.

“Some of the focus is perhaps not treatment activities, but it is immediately adjacent,” Godbole said. “It is the backbone of making those lifesaving programs work.”

The strategy identifies CHW programs as ripe for integration, able to deliver HIV services, but also immunizations, for instance. But there is little clarity on how deeply U.S. aid cuts have affected CHW programs outside of the HIV sector and whether enough health workers are left to take on all of these tasks.

Indeed, there is a broader concern that the strategy fails to account for how cuts to other health programs, including U.S. support for efforts to battle malaria and tuberculosis or to provide childhood immunizations, will affect HIV services. People scrambling for scarce resources may not prioritize HIV interventions.

“You cannot have a functioning HIV program in the context of a decimated human resource landscape for every other health issue,” Bass said.

The concerns do not end there.

The administration has not released any PEPFAR program data since 2024. And there are no plans to do so in the future. The new strategy tasks countries to meet targets in order to unlock future funding, but Godbole wonders how governments can be held accountable without transparent data.

In adopting a bilateral approach to negotiating HIV financing, Schwalbe said there was a risk of the Trump administration imposing unrelated conditionalities — such as access to markets or minerals — on support.

And following the elimination of USAID and the firing of many global health experts from the U.S. government, there are questions about who is going to negotiate these memoranda, particularly given the short timeline laid out in the strategy.

“There is some amount of relief that there is a commitment to continuing some of the good work that has previously been done,” Godbole said. “But generally, there are concerns around the timeline and some of the more operational details of how this is going to play out.”