Try to grasp it: 6.3 million deaths from AIDS because of U.S. cuts

Commentary: We need to act because millions of lives will be lost if nothing changes.

UNAIDS: “Without funding from the United States, within four years, 6.3 million people will die and 8.9 million will newly acquire HIV. Around 370 000 babies will acquire HIV, and without treatment, half will not live to see their second birthday.”

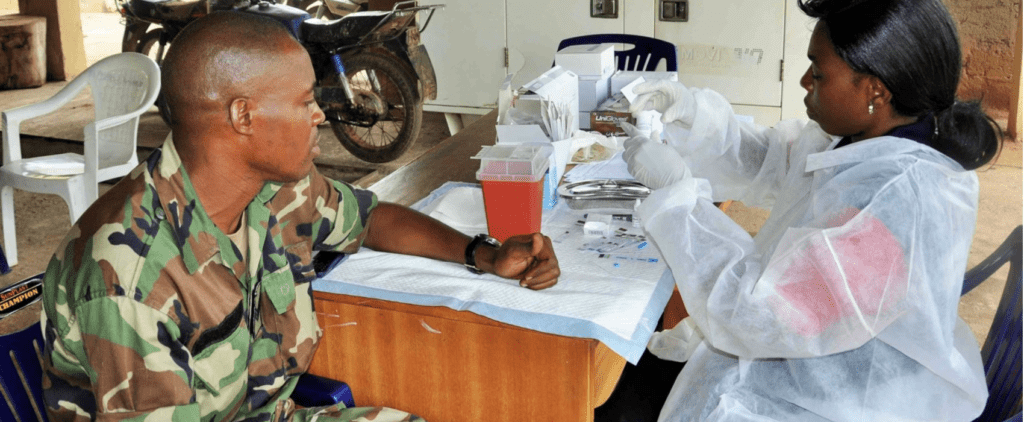

The immensity of the unfolding tragedy at shuttered HIV clinics worldwide makes it hard to contemplate the impact of the U.S. decision to cut off much of its global anti-AIDS program.

In the following modestly edited essay, translated from French, Serge Douomong Yotta, advocacy director of the anti-AIDS group Coalition PLUS, tries to bring the public’s attention back to what’s at stake as the United States, the United Kingdom, France and other nations slash their support for the war against AIDS, which had been waged most vigorously by the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (Pepfar).

He has many suggestions of how to respond.

Here’s a reminder of some of what has been happening to Pepfar since President Donald Trump froze U.S. foreign aid funds on Jan. 20.

Status of Pepfar, according to KFF Health News:

- Loss of thousands of HIV health workers in Kenya, Malawi, South Africa and Mozambique; disruptions to diagnostic and treatment services for pregnant women and children in Zimbabwe; partial or complete cessation of community outreach services in Angola and Eswatini; and the expected loss of a quarter of the workforce of the largest network of people living with HIV in Ukraine.

- 86% of anti-AIDS programs say that clients would lose access to HIV treatment within one month if the freeze was not lifted.

COMMENTARY

The global war on AIDS that we are abandoning

By Serge Douomong Yotta

It took me a while.

Time to understand. To digest. To put into words what is currently at stake for people living with HIV in Africa and in the Global South as a whole.

We are witnessing an organized desertion from the war on AIDS.

While [politicians] talk about “priorities”: trade, customs, security, immigration, defense, etc., they forget the essential: AIDS could still kill 6.3 million people by 2030 if nothing changes.

Consequences similar to the casualties in a war

Nearly three months after the announcement of the freeze on US development aid funding, what is the outcome in the fight against HIV? The question takes on added meaning because the consequences of this halt are similar to those of a war. …

UNAIDS estimates that the permanent dismantling of Pepfar would result in 6.3 million AIDS-related deaths by 2029, almost as many as between 2001 and 2004, when treatment was still largely inaccessible. It would also result in 3.4 million orphans, 350,000 new infections among children, and 8.7 million additional infections among adults. [The author also notes a study in The Lancet HIV that projects up to 2.9 million additional HIV-related deaths by 2030.]

The 6.3 million deaths represent a human toll greater than several wars that humanity has experienced, excluding the two world wars.

What is coming up by 2029, if we do not invest in stopping AIDS (6.3 million deaths), is the equivalent of the approximate cumulative death toll of the Chinese Civil War (1,200,000 deaths), the Vietnam War (1,200,000 deaths), the Iran-Iraq War (850,000 deaths), the Russian Civil War (800,000 deaths), the Indochina War (385,000 deaths), the Mexican Revolution (200,000 deaths), the Spanish Civil War (200,000 deaths), the war in Afghanistan (150,000 deaths), the Russo-Japanese War (100,000 deaths), the Rif War [1921-1926 in northern Morocco] (100,000 deaths), the first civil war in Sudan (100,000 deaths), the Russo-Polish War (100,000 deaths), the Biafran War [1967-1970 in Nigeria] (100,000 deaths), the Chaco War [1932-1935 between Bolivia and Paraguay] (90,000 deaths), the Abyssinian War [1935-1937 between Italy and Ethiopia] (80,000 deaths), the war in Ukraine (9,701 deaths), and the war in the Gaza Strip (50,523 deaths). The cumulative death toll from these 17 wars is 5,705,523, far below the expected 6.3 million deaths.

Five countries, contributing more than 90% of international funding for the fight against HIV, have announced reductions in international aid of between 8% and 70% between 2025 and 2026. This is the case, for example, of the United Kingdom (40% reduction by 2027), France (37% reduction), and Belgium (25% reduction). However, all these countries have agreed to increase their defense budgets: 2.6% for the United Kingdom, while the President of the European Commission has confirmed her desire to encourage states to spend more on defense. Almost all NATO countries have increased their military spending by 2024, with the majority meeting the target set in 2014 to devote 2% of their GDP to defense, a target that was only met by 11 of the organization’s 30 states in 2023.

The resources are therefore there. But the priorities are elsewhere, because the victims of AIDS are elsewhere.

How could we forget?

What could have made the powerful forget the history of AIDS? From Princess Diana’s handshake [ungloved, with an AIDS patient in 1987] to Clémentine Célarié’s militant kiss [on TV with an HIV-positive man in 1994]? From the historic creation of UNAIDS in 1996 and then the Global Fund in 2002, to the political commitment of President Bush who launched Pepfar in 2003? From cinematic successes like the movie “Philadelphia” in Hollywood [1993], to the activist fundraising evenings of Amfar [starting in 1993] and Sidaction [starting in 1994] where the entire world of culture and media was outraged by the cost of inaction and called on the powerful to make a strong political commitment?

What happened so that the high-level meetings of the United Nations on HIV, the political declarations and especially the mobilizations of activists around the world within the framework of international conferences (ICASA, Afravih, IAS, etc.) calling for equity in access to antiretroviral treatments were thus completely forgotten? What happened so that the transmission of the virus from mother to child, the rights of vulnerable people and the infection of adolescents and young people no longer move anyone? What happened to ensure that the premature departure of heroes and stars (Freddy Mercury, [plus Rock Hudson, Keith Haring, Anthony Perkins, Arthur Ashe, Liberace, Rudolf Nureyev], Thierry Le Luron, Michel Foucault, Daniel Defert, Elizabeth Glaser, etc.), friends and activists … and the 42.3 million people who have died of AIDS since the beginning of the epidemic no longer oblige us to fight this virus?

There are wars that can be prevented and wars that surprise us. There are deaths that can be prevented and deaths that surprise us. This phrase has been echoed by several political figures, notably [U.N. Secretary-General] Kofi Annan, who recalled that “inaction costs lives,” and [German Chancellor] Angela Merkel, after the Syrian refugee crisis, who acknowledged that “history will judge us according to our ability to respond to human tragedies.” In the current context, who will be judged by history? The responsibility and the cost of inaction are so heavy (6.3 million deaths) that naming those responsible—the international community—seems madness, because I dare to hope that it knows it is being watched and expected. Actively.

What needs to be done: Replenishing the Global Fund

At this time of collapse of achievements, community experience and expertise should answer the call and form the emergency battalion. The Global Fund Replenishment [a gathering of public and private contributions for 2026-2028 operations of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria], scheduled for London in September 2025, is an opportunity to at least maintain basic achievements. The Global Fund needs US$18 billion to save 23 million lives between 2027 and 2029; this is a minimum amount, as the most accurate scenario would be for the Global Fund to contribute US$28.1 billion to the fight against pandemics. But the Global Fund alone cannot prevent the impending massacre (6.3 million deaths). What other levers can be activated to anticipate this?

What needs to be done: Freeing up needed supplies, skills and technology

Countries with significant technological advances have an opportunity to transfer skills, share technology, and ensure that countries in the Global South quickly have the capacity to produce all the necessary supplies for HIV prevention and care.

This is not a utopian vision. Several initiatives are already underway and deserve special attention to strengthen this approach to preventing this massacre. First, the pandemic treaty [which will be proposed to the World Health Assembly starting May 19 in Geneva, Switzderland]. More than ever, this treaty should … facilitate technology transfer and the waiver of intellectual property rights on patents. … This would allow countries in the Global South to locally produce diagnostics, vaccines, and treatments, thereby reducing their dependence on countries in the Global North and private industry. Even if a fully consensual agreement remains difficult to achieve, … significant convergences remain possible. The pandemic agreement could constitute a political opportunity to prevent the great massacre.

What needs to be done: Relieving debt and improving international cooperation

Then, the implementation of the Lusaka Agenda [a list of policy recommendations for improved health in the Global South, most actively pursued by the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, Senegal, and South Sudan], building on the Abuja Declaration and more aggressive advocacy for debt relief for countries in the Global South, could be an opportunity to accelerate the process toward health sovereignty. This will be all the more rapid if civil society and the communities concerned are systematically involved to contribute all their expertise accumulated over 40 years of fighting HIV.

What needs to be done: ‘An epidemic cannot be fought with business plans’

Effective health sovereignty does not boil down to viewing health as a business, as advocated by the U.S. administration during the first official meeting since the beginning of the crisis between the heads of the Africa CDC and the US CDC on March 26, 2025. Profit cannot be the compass of care; care is not a service rendered but a human right, even an ecosystem right, a justice for the living. An epidemic cannot be fought with business plans. It must be fought with strong, coordinated, long-term funded health systems, including community-based ones, based on science and solidarity.

Moreover, health is already a sector of economic activity, with markets and return-on-investment logics. The Global Fund rightly states in its 2025 investment case that every dollar invested in the fight against HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria generates health gains and economic returns of up to $19. Thus, the US$18 billion to be raised during the 2025 replenishment would generate economic benefits of US$323 billion over the period 2027-2029.

What needs to be done: New taxes to pay for better health?

Instead of viewing health primarily as a business, good old-fashioned ways exist to harness business to serve health. In an op-ed published in La Croix, a collective of associations and humanitarian organizations, for example, calls on France to revive its tradition as a pioneer in innovative solidarity financing to combat malnutrition by, for example, introducing a “soda tax.” The Africa CDC is also considering advocating for a solidarity tax on all airline tickets sold on the continent, or even taxes on alcohol and tobacco.

What needs to be done: Working together, not blaming DEI and ‘wokeism’

To our states and our political leaders, let us not mistake our enemies. Blaming wokeism and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) policies—the bulwark against racist programs and ideologies, LGBTIQ+ communities, and the fight against gender inequality—does not honor the years of struggle for equity and social justice. … [The] African continent will need all its children to face the structural challenges that await it. Homophobia, transphobia, and sexism are merely distractions from the impending massacre (6.3 million deaths). All activists must be mobilized, whether we are pan-African activists, feminist activists, environmental and nature activists, or LGBTIQ+ activists. … Everyone, within their own field of action, should find space for the common good. …

The phrase “it’s now or never!” befits the gravity of the moment. We must all act, urgently, now. We must inform ourselves, adapt, mobilize, form a united front, and develop responses that leave no one behind.