Queers and racialized people ‘don’t have the privilege of hiding’, artist says

Moïse Manoël-Florisse, is an African-Caribbean online journalist keeping an eye…

French-Caribbean artist tells of sudden childhood education in racial and gender bias.

The first day of fourth grade in France taught Caribbean queer artist Estelle Prudent how society treats marginalized people:

“When I arrived in France at elementary school, I was confronted with racism. … At the start of [fourth grade], the tables were already set with the names of each pupil, and I was looking for my table. And there was Jérémie, a blond-haired, blue-eyed boy sitting in my place.

“No sooner had I started complaining about him to the teacher than the boy exclaimed in front of my classmates, “You stink, you monkey!’ The teacher added, ‘You’re not going to start crying now’ to make me feel guilty.

“As a result, I spent the rest of the year at the back of the class, with my new classmates Shéhérazade and Ravi, who were both racialized like me. [“Racialized” means assigned by society to a racial category that is subjected to oppressive or discriminatory treatment.]

“I became aware of racial and gender domination from that point on.”

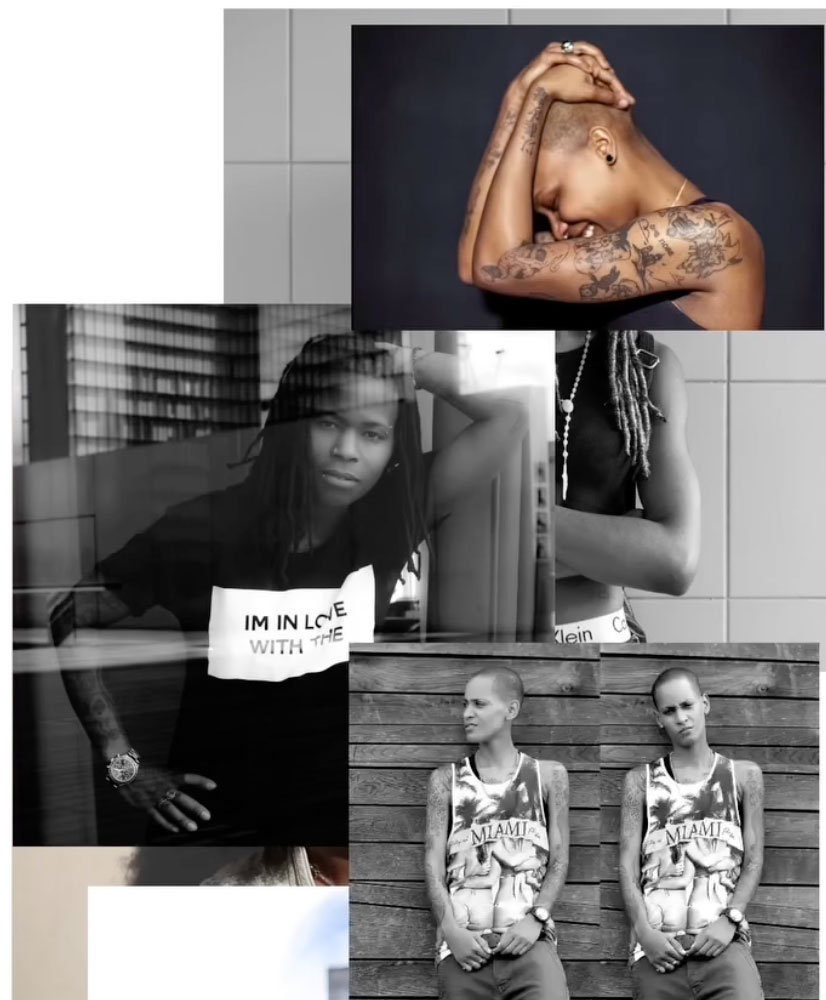

Prudent is now an award-winning artist who exhibits photos of black and racialized people from marginalized communities in the Paris suburbs. Last year, she won the Utopia Prize for her photography and related artwork. Prudent gave this interview in connection with a showing of her work.

Estelle Prudent: “I’m a queer activist and decolonial artist, and all my projects contribute to a critical study of studies of domination.

My background stems from the fact that my father is Guadeloupean and my mother is Martiniquan, and that I spent the first years of my life in the West Indies.

Early in life I became aware that there was a gap between our lives and the visual aesthetics that are conveyed in society.

Later, as an adult, while strolling through the streets of Lyon where I was studying, I [found] a bar called “Le Colonial”.

Wanting to question this colonial heritage at my art school, I then came up against a wall, finding no supervisor willing to accompany me on this theme, while there were very few representations in the public space of queer and black figures.

‘It’s not just about sex. It’s about how we live, how we die, how we love each other.’

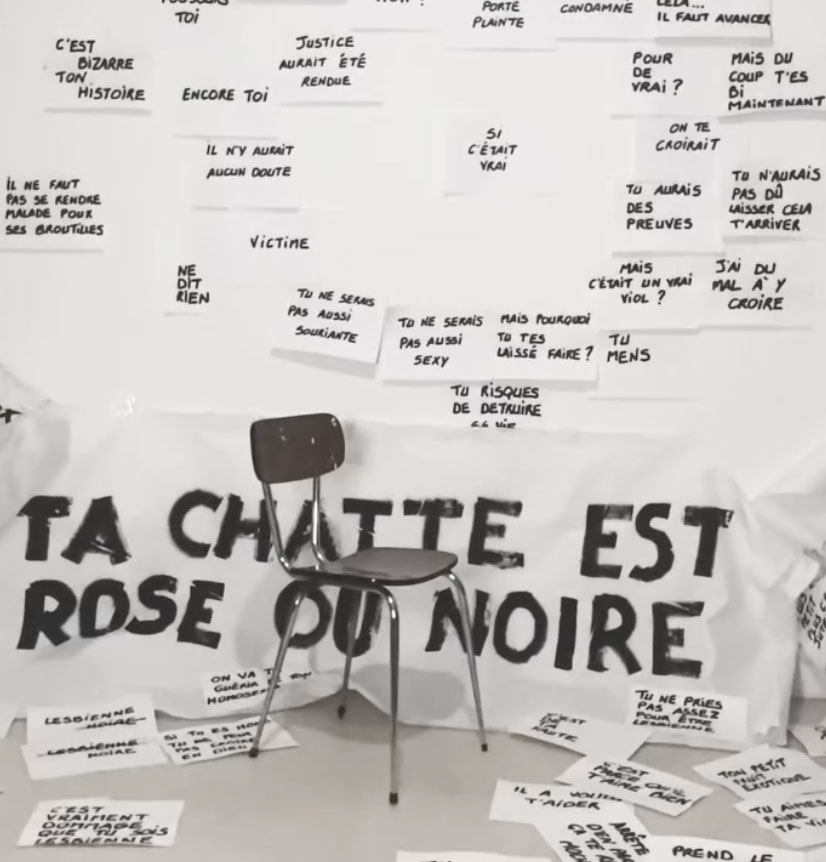

When these representations did exist, as at Le Klub, a former Afro-LGBT+ nightclub in Paris, they were extremely disturbing, overly erotic, with hypersexualized photographs and far removed from our realities.

I became aware that there was a gap between our lives and the images and visual aesthetics that are transmitted through them. And that we needed to reappropriate our narratives, through art, to present ourselves to the world as we are.

So, when we talk about homosexuality around us, it’s not just about sex. It’s about how we live, how we die, how we love each other. But the lack of visibility of queer and racialized people doesn’t help educate our communities.

That’s why racialized people don’t understand queerness, and why white queer people don’t always understand intersectionality. [“Intersectionality” refers to the ways that groups’ and individuals’ various social and political identities create unique combinations of discrimination and privilege.]

Creating safe queer spaces

And even within lesbian groups, there are micro-aggressions. In Lyon, for example, when I went out to a nightclub called Le Marais, I was turned away at the door and told that this was a special place, because I didn’t have the codes or aesthetic of the “dyke” community.

I realized that we needed to create safe spaces for queer affirmation. And that’s how my first projects as an artist came about.

My leitmotiv is to take the spaces necessary for our power and flamboyance.

The ‘Queer Superpower’ project (2016 – today)

When I graduated from the École des Beaux Arts de Lyon, unlike my classmates who were offered artist residencies to develop their work, I couldn’t find a space for my collages (the “Pense-bêtes” project) or my photos (the “Queer Superpower” project) where I dealt with racism. In fact, on several occasions, I’ve been asked if racism even exists.

I work in a store, because the other big challenge for queer artists is to make a living while continuing to produce work that tells the story of our society.

Secondly, even supposedly “safe” spaces like the LGBT center in Paris aren’t safe after all.

In 2017, I loaned 1,000 drawings to an exhibition there, which after 30 days were torn up and thrown away by a trainee. For me, this represented months of work, as well as the symbolic dimension of being a black lesbian woman who sees her work totally devalued, vulgarly destroyed, as if the themes I was exploring were light and frivolous, even superfluous.

In my life as an artist, this disastrous experience helped me understand that exhibiting in exhibition spaces is also complex. And that a showing could be perceived as exotic. And so the “Pense-Bêtes” project was born.

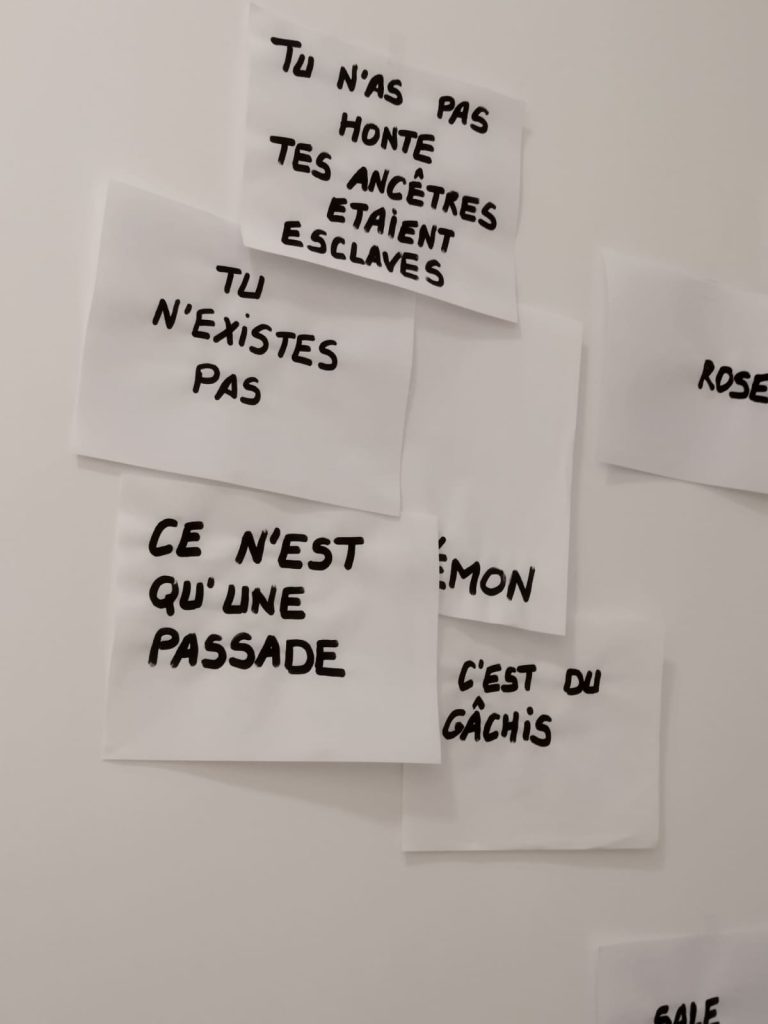

The “Pense-Bêtes” project (2016 – today)

“Can you tell us more about it?”

Estelle Prudent: “Pense-Bêtes” [a phrase that means “Reminders” though literally the words translate as “Think Beasts”] is a project that involves spontaneous writing when situations of discrimination arise, in order to put words and pictograms to describe things: “lesbophobia”, “racism”, “paedophilia”.

The result is sketchbooks and drawings based on each of these words. The aim is to set the word free through a collective project, giving everyone sheets of paper and pens to express themselves.

The challenge of exhibiting queer art in the West Indies

“How did your last major exhibition of 2024 go, and do you have any plans for your native West Indies?”

Estelle Prudent: “Being a winner of the Utopia Prize since last September — a prize that rewards the best committed LGBT+ artists — I was able to access large spaces like the Maurice Ravel space in the 12th arrondissement, for 10 days.

Previously, I’d worked with a lot of small collectives, but it was difficult to prepare exhibitions and find spaces to exhibit in, while at the same time having to work on the side, because making a living from your art isn’t free.

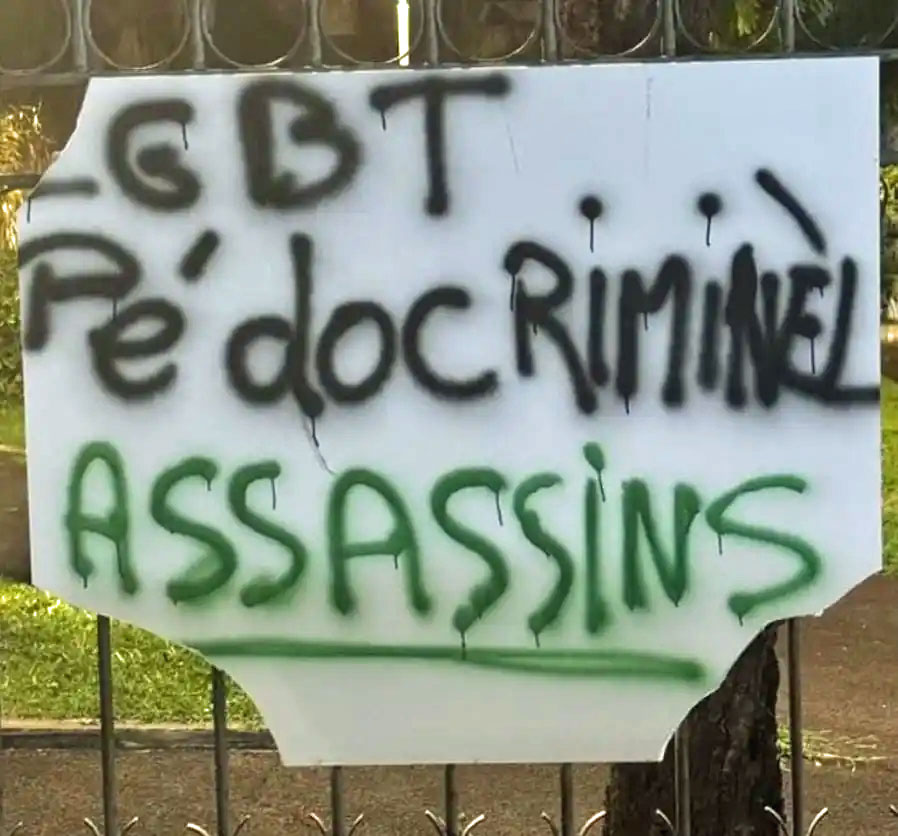

As far as the West Indies are concerned, I was there two years ago, and I’ve made some contacts to be able to exhibit one day, and why not do an exhibition outside the walls?

Exhibiting in public means stepping out of your comfort zone and regaining power, because it is in public spaces that discrimination occurs.

[The exhibition “Lanmou-nou” by Adeline Rapon, the first of its kind in Martinique to showcase in public spaces Caribbean LGBT+ people who love each other, was vandalized on the gates of the Schoelcher Library in Fort-de-France last October.]

Finally, our societies, both here and there, need art because we need to be nourished emotionally. And we also need to be mentally regenerated, because in the artistic treatment of a work, we also see ourselves through other perspectives.

For example, one day a viewer told me that for the first time she saw, through one of my works, a person who is like her mother.

With our queer lives, our experiences, and the subjects we address, we don’t have the privilege of being able to hide.

As I like to say and repeat over and over again: “You are an important person. Take care of yourself.”

Surviving in silence: Qtalk provides guidance for trans woman in northern Nigeria