How Trinidad lost the right to gay sex

LGBTQ rights activist filed the suit that legalized gay sex. Now he vows to appeal

Below, LGBTQ rights journalist Rob Salerno, an editor for Erasing 76 Crimes, analyzes the court ruling that revived the anti-sodomy law of the Caribbean island nation of Trinidad and Tobago. (Click here to subscribe to his LGBTQ Global newsletter.)

ANALYSIS

Queer people suffered an enormous and surprising setback on Wednesday when the Court of Appeal overturned the 2018 ruling that struck down the Caribbean country’s laws banning gay sex.I’m going to try to break down what happened here.

In 2017, UK-based Trinidadian activist Jason Jones filed a challenge to the country’s buggery and serious indecency laws – the laws which effectively ban gay sex, as well as oral and anal sex between straight people. A year later, a court on the island ruled in his favor, finding that the laws were unconstitutional insofar as they applied to consensual acts in private.

Trinidad became part of the leading edge of a wave of legal challenges that saw laws banning gay sex struck down across the region. Belize had preceded it in 2016; shortly after the ruling, a coordinated set of legal challenges were launched in all of the other former British colonies in the Caribbean islands. By 2024, activists had won challenges to sodomy laws in Antigua and Barbuda, St Kitts and Nevis, Dominica, and Barbados – with cases still pending in Grenada and St Lucia. Around this time, these rulings were mirrored in court decisions striking down anti-gay laws in other former UK colonies, including Mauritius, Botswana, and India, making them part of a larger global trend.

But there were some warning signs on the horizon. In 2023, Jamaica’s Supreme Court upheld its sodomy laws, finding they were protected by a “savings clause” in the country’s constitution, which protects pre-independence laws from constitutional scrutiny. Last year, St Vincent and the Grenadines’ high court issued a baffling ruling upholding its sodomy laws.

So what happened in Trinidad and Tobago? Well, in the original case, Jones had argued that although the constitution has a “savings clause” – as do most former UK colonies in the Caribbean – the clause didn’t apply, because the colonial-era buggery law (part of the 1925 Offences Against the Person Act) had been repealed and replaced by a different buggery law (the 1986 Sexual Offences Act) which carried a significantly stiffer penalty, up from a maximum of 5 years in prison to 25 years.

The colonial-era “gross indecency” law had similarly been replaced with a “serious indecency” law. The judge found that this rendered the savings clause inapplicable and then found that the laws were unconstitutional. The government of the day vowed to appeal.Seven years later – yes, seven years later – the Court of Appeal issued its 2-1 judgement siding with the government.

The 200-page judgement is not yet available online – the website seems to run about a week behind – so I can’t read it to fully understand the reasoning.

But reports seem to indicate that the court decided that the 1986 buggery and serious indecency laws are indeed unconstitutional but then reinstated the repealed 1925 buggery and gross indecency laws in their place.

I fully do not understand how the court can argue that this is not legislating from the bench, when it is specifically undoing an act of parliament – repealing the old act.

The net effect of this is that anal sex and oral sex are both illegal in Trinidad and Tobago again, albeit with lesser penalties than they held in 2017.

However, the judges found that the gross indecency law does not apply to married or heterosexual couples conducting the act in private consensually).

Jones has vowed to appeal this to Trinidad’s highest court, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the UK, but, to be fully honest, I don’t like his chances. The JCPC has ruled, and recently, that “savings clauses,” including specifically Trinidad and Tobago’s, are still active and in effect (in a case upholding T&T’s death penalty).

Possibly the best line of argument is that the CoA erred in the way it applied the savings clause, given the history of this buggery law specifically.Mixed up in all this are political questions around the law and the courts. Both major parties in T&T have been pretty proudly homophobic – the opposition even more than the party that’s been in government through the entire case. The country is in the midst of an election to be held on April 28, but that’s unlikely to change the political calculus.

The current government would like to abolish the Privy Council as the court of final resort and move to the local Caribbean Court of Justice instead, as five other neighboring states have, but it lacks the needed supermajority support in parliament to do so.

Moving to the CCJ would be relevant, because the CCJ has generally ruled that “savings clauses” in Caribbean countries’ constitutions have generally expired and are no longer valid. If Trinidad and Tobago moved to the CCJ, it would be more likely to strike down its buggery laws.

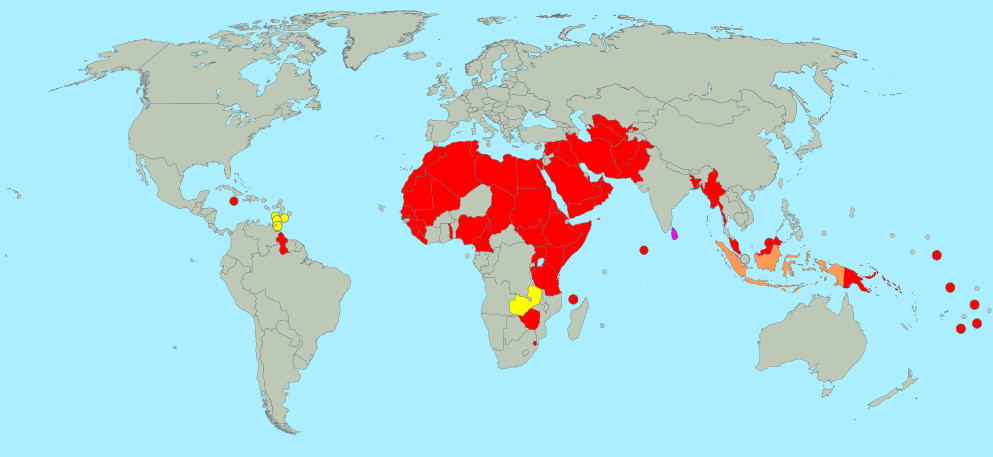

But only time will tell what will happen here. Jones is filing his appeal to the JCPC, but it’s likely years before the case is heard, and years more before the JCPC issues its ruling. During that time, Trinidad is, unfortunately, returned to the list of states that criminalize LGBT people. Bringing the total back up to 66 countries with laws banning gay sex.

Not so long ago they were flying the rainbow flag at government buildings in Port of Spain, in solidarity with its gay citizens. What the hell is wrong with people. Progress has always been the goal, not regress. People everywhere have lost their cotton picking minds.