The glitter and the grit: Inside Nigeria’s queer ballroom subculture

‘As a queer person, it gives me a family and a safe space.’

In Nigeria, where same-sex marriage is criminalised and the larger part of society is openly discriminatory and violent toward queer folk, the underground ballroom scene provides a community for queer Nigerians to discreetly gather to express themselves through dance, fashion and language.

When Countess Sasha Seduction, a Nigerian non-binary drag queen, got to attend their first ballroom experience, a 2022 Halloween ball in Lagos, Nigeria, it felt like a dream. This year, they got to attend two and were excited about how amazing the underground community was and the warmth that the space provided.

“As a drag queen, it gives me somewhere to be, to inspire people, to perform. As a queer person, it gives me a family and a safe space. We’re almost forced to live in fear all the time and the ballroom is just a fantasy island where everything doesn’t matter but the people you are with, who are [also] queer! [This] is important because we don’t have that in Nigeria.”

The global ballroom scene can be traced back to the 1960s in the United States. It was a form of refuge for African American and Latino drag queens, and trans-women who were often ostracised from mainstream society due to their gender identity and sexuality. They also faced racial discrimination within white-dominated balls – so much so that they had to wear pale make-up to make them look lighter-skinned and increase their chances of winning competitions. These minorities eventually found refuge in Harlem, where they gathered in ballrooms to organise and compete as a way to express their identities and find acceptance. The ballroom competitions were a way for the participants to showcase their talents in various categories, including modelling, voguing, and dance.

However, this was by no means the birth of ‘drag’ as a concept. One of the first known persons self-described as ‘a queen of drag’ was William Dorsay Swann. A black man born on a plantation before the Civil War and freed under the Emancipation Proclamation, Swann threw elaborate balls in Washington, D.C., with many other black men participating. Swann’s balls were raided multiple times and usually ended up with him and others being arrested, making him one of the earliest arrests on record for female impersonation in the United States. When he was arrested in 1896, wrongfully convicted, and sentenced for running a brothel, he became the first American on record to protest and seek legal action against the discrimination and criminalisation of queer people. Even after Swann retired from the drag and ballroom scene years later in his old age, his brother Daniel J. Swann was still a part of this community.

The ballroom scene has since evolved from a form of entertainment into a cultural phenomenon and subculture across the world, transcending borders and customs. As a safe space for queer people, it is significant as a space for self-expression without fear of prejudice or discrimination; it is also a place where members of the LGBTQI+ community can come together and celebrate themselves.

In Nigeria, where same-sex marriage is criminalised and the larger part of society is openly discriminatory and violent towards queer folk, the underground ballroom scene provides a community for queer Nigerians to discreetly gather to express themselves through dance, fashion and language. While ballroom in Nigeria was quite a thing in the early 2000s, the passing of the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act in 2014, which prohibits the meetings of gay clubs, societies, and organisations, saw its vibrancy clamped down.

Young queer Nigerians are now actively trying to rekindle ballrooms, albeit inconspicuously. Fola Francis, a Nigerian transwoman and activist who passed away last year, told Minority Africa that the underground ballroom scene in Lagos was born out of the need for queer people to have spaces where they could not only feel safe but also have fun.

“That was why I threw my own ball [in 2022], it was an attempt to create a space for self-expression in our way. At first, the balls set out to mirror the New York ballroom scene but over time, it became amped up with that Nigerian extra-ness. Now, it’s like an Owambe party infused with actual ballroom. Attendees come to the venue with their outfits in their bags, and there are also changing rooms for them to get dressed and get their make-up done,” she said.

Participants and attendees at these balls are thoroughly vetted to avoid the events from being penetrated by kitos [blackmailers posing as LGBTIQA+ people] or even law enforcement officers.

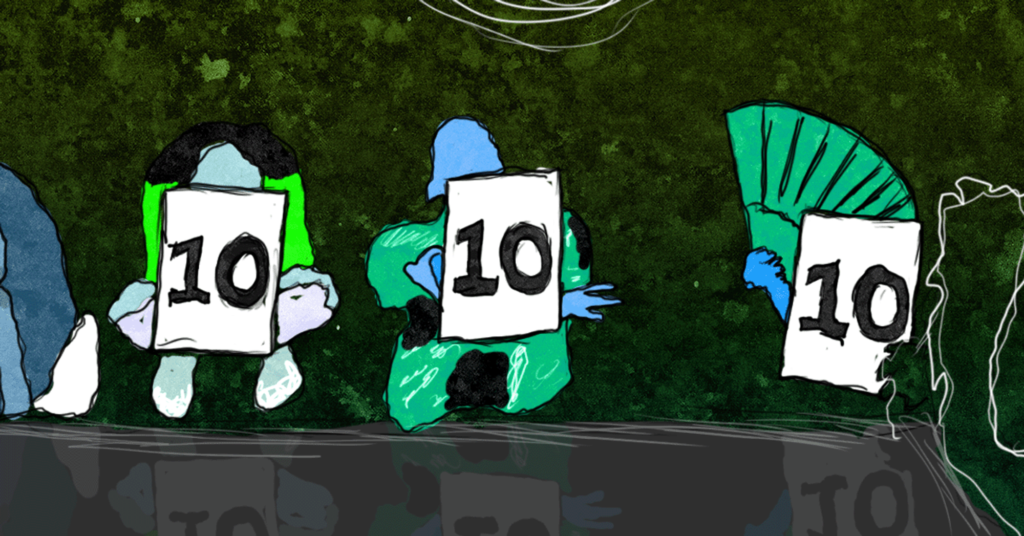

One of the most significant aspects of the ballroom scene is the way it has influenced fashion and style. The fashion of ballroom is known for being ‘out there’ – its extravagance and creativity, big hairstyles, and outfits that feature bold colours, glitter, and intricate designs – helping many LGBTQIA+ individuals to stand out and express themselves in a society that can be hostile to their lifestyle. This vibrant fashion has had a major impact on the fashion industry, with many designers drawing inspiration from ballroom culture.

Nigerian designers like Oshobor, Manell and Taofeeq Abólárìnwá Yahaya are boldly making space for queerness in their designs. While this is not apparent in most everyday apparel, it’s a sight that is colourfully on display by attendees during fashion events like the Lagos Fashion Week and the GTB Fashion Week. Men, women, and non-binary people can be found expressing themselves in styles, colours and cuts that might be usually too outlandish or found questionable in their regular lives. There is also a safe space for queer people who do not necessarily want their sense of style to flashily draw attention but simply look to the fashion of Nigerian designers like Emerie Udiahgebi and Vangei for the inclusion that society denies them.

Vicwonder, Nigerian activist and head stylist of House Vicwonder, finds fashion to be a tool of expression and activism for queer people and one of liberation for him. “Fashion allows me to feel things and so if I’m feeling a feminine energy, I can channel that through my fashion, vis-à-vis masculine energy. The universe thrives on these energies and so I thrive on it because I don’t shy away from any of it.”

Language is also an important part of ballroom culture. The ballroom community has seen a chunk of its vocabulary transition into mainstream culture. Phrases like “throwing shade,” “slay,” “eat,” “mother” and “reading” all have their origins in drag queen competitions and interactions between different houses but have now become common parlance, thanks to ballroom culture. This unique language, which might have been adopted by many who do not understand its significance, has helped to bring the community together and create a sense of belonging among its members.

The ballroom scene represents a cultural affirmation of the queer identity and has provided a platform for self-expression and creativity. The origins of ballroom in the United States are rooted in marginalisation and a search for acceptance. Similarly, the ballroom scene in Nigeria has emerged as a response to discrimination and violence against the queer community. As the ballroom scene continues to evolve and gain momentum in Nigeria, it represents hope for the queer community in a society that can be hostile to their existence. It is a celebration of individuality, self-expression and creativity, and it represents a continued fight for acceptance, tolerance, and inclusion for Nigeria’s LGBTQIA+ community.

This story was first published on Minority Africa and appears with permission in this publication.