U.S. Supreme Court laid foundation for Ugandan ‘Kill the Gays’ ruling

Colin Stewart is a 45-year journalism veteran living in Southern…

Ugandan court mirrored U.S. justices’ insistence on tradition, disregard for human rights

The Ugandan court that endorsed the nation’s 2023 “Kill the Gays” law drew inspiration from the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2022 decision overturning its previous Roe v. Wade ruling that had established abortion rights.

In explaining their support for the 2023 Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA), the Ugandan Constitutional Court said that the U.S. Supreme Court had established a new standard that considered “history and traditions” more important than individual human rights.

The Ugandan court similarly considered traditional homophobia to be an adequate basis for the AHA’s provision calling for the execution of homosexuals who persist in consensual same-sex activity, which it categorizes as “aggravated homosexuality”.

US Supreme Court Ruling Cited as Uganda Upholds Anti-Gay Death Penalty

By Aila Slisco

The U.S. Supreme Court decision that struck down Roe v. Wade was cited in Uganda’s decision to uphold an anti-gay law calling for the execution of those who practice “aggravated homosexuality.”

The Constitutional Court of Uganda on [April 3] used the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization as justification to largely uphold Anti-Homosexuality Act 2023, arguing that the U.S. court’s conservative majority had established a new standard for “human rights jurisprudence” that places “history and traditions” over individual rights.

Dobbs, which in 2022 instantly criminalized abortion in many U.S. states, was cited as a “basis for the court decision” to uphold the gay death penalty law, which the Ugandan court said had been passed last year following “public outcry” over the supposed “forced recruitment of children into homosexual acts.”

Uganda’s constitutional court praised the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to strike down Roe v. Wade, writing that the court had “considered the nation’s history and traditions, as well as the dictates of democracy and rule of law, to over-rule the broader right to individual autonomy.”

The Ugandan court also cited an “absence of consensus at the global level regarding non-discrimination based sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression and sex characteristics” as justification for the anti-gay law.

The law defines “aggravated homosexuality” as gay people who: engage in gay sex involving a minor; have HIV or disabilities; are elderly; or get convicted of non-aggravated homosexuality more than once.

Homosexuality not considered to be “aggravated” under the law is punishable by to a life sentence in prison, while “promoting” homosexuality carries a sentence of up to 20 years. Attempted homosexuality and aggravated homosexuality are punishable by sentences of 10 and 14 years, respectively.

While the death penalty for “aggravated homosexuality” was upheld, the constitutional court’s decision did strike down some other parts of the law, including provisions that criminalized renting property “for homosexual purposes” and a requirement that Ugandan citizens “report acts of homosexuality” to police.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision intensified a political firestorm over abortion rights and prompted some to predict that the court’s conservative majority would soon turn their attention to overturning other rights that some conservatives oppose, including protections for the LGBTQ+ community.

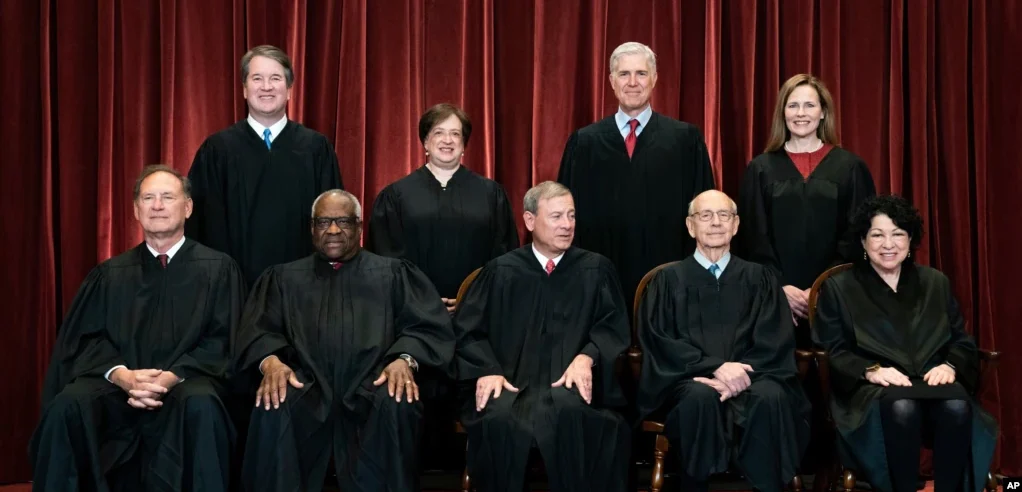

In his concurring Dobbs opinion, conservative Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that he hoped to “correct the error” of the Supreme Court’s rulings in Lawrence v. Texas, Obergefell v. Hodges and Griswold v. Connecticut—which struck down anti-sodomy laws, established same-sex marriage equality and established the right for married couples to use contraception, respectively.

Indeed, it sounds very odd that another independent nation would quote the United States Supreme Court as justifying an ideological rationalization for its own legal opinion,

There is the paradox that British Commonwealth nations claim on the one hand that they reject colonial laws & British diplomatic protests about these laws are called colonialist interference, whilst on the other hand embracing many of the colonial ideology & laws they profess to reject. They seek compensation for colonialism’s exploitation of their countries whilst embracing what was once the imposed religion of Christianity, whilst exploiting colonial laws to their political advantage. That said, their actions, promoted by the US Christian Right, show an inferiority complex and a seeming craving to return to being a colony.