Queer lives in fragile Sudan: Amid turmoil, glimmers of hope

Kikonyogo Kivumbi is the executive director of the Uganda Health…

Queer people have long been excluded from Sudans’ political life and social mainstream, but some believe the country’s currently tumultuous transition to democracy presents an opportunity to make progress toward recognition of LGBTIQ+ rights.

Hopeful signs appear in a report compiled by Bedayaa, a Nile River Valley organization advocating for LGBTQI people in Egypt and Sudan.

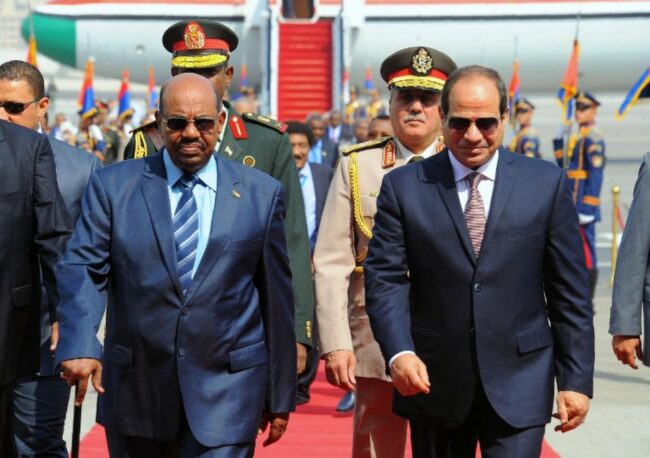

The Needs Assessment Report sheds light on what can be done to support queer organising and rights demands in the majority Muslim country where death penalty for same-sex adult intimacy was only lifted last year, following a coup that removed the country’s long-time dictator, President Omar al Bashir.

It discusses critical topics such as access to justice, health care, safety and security of person and property, shelter, education, capacity-building, sexual and reproductive health and rights, and non-discrimination, among others.

Those issues exist in a nation with a legal system similar to most Arab states in Africa and the Middle East, which inherited strict laws against homosexuality from the French or British colonial systems of justice, and also are ruled or influenced by various traditions of Islamic sharia law.

Activists’ advocacy for recognition of LGBTQ+ rights comes amid renewed demands by Sudanese political actors and stakeholders demanding broader inclusion in the governance of the country.

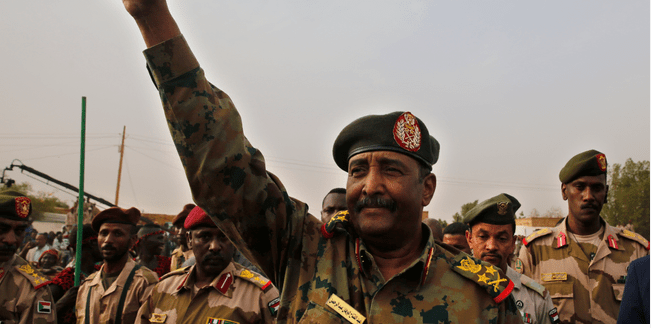

News reports indicate that thousands of demonstrators gathered in front of the presidential palace in Khartoum on Saturday calling for the military to seize power as Sudan grapples with the biggest political crisis in its two-year-old transition toward democracy since the toppling of the 30-year dictatorship of President Omar al-Bashir. Since then, military and civilian groups have been sharing power in an uneasy alliance.

But following a failed coup attempt in September attributed to forces loyal to Bashir, military leaders have been demanding reforms to the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) coalition and the replacement of the cabinet.

Amid this turmoil, Bedayaa works to promote the acceptance of homosexuality in Egypt and Sudan and to help LGBTQI community members to live a life free of discrimination or stigma. Their mission is to create a safe space that will allow all LGBTQI people in the Nile Valley to communicate, exchange knowledge, discuss issues, share experiences, and work on improving their lives and themselves.

The report suggests that there is a window of hope for demanding rights for queer people in Sudan.

The participants in the preparation of the report expressed hope that political change could open spaces for LGBTQI+ recognition and advocacy in a relatively safe environment.

The report added:

“The transitional period Sudan is currently going through aims to bring about political change which offers a window for legal reforms. Many of our interlocutors participated in the uprisings. They mostly have hope that a new era of equality can happen.

“As [an interviewee named] Lola puts it, ‘When I participated in the uprising I did so for the same reasons of freedom, peace and justice — the revolutionary slogan. I wanted justice, not only legal but also social. As a queer person, I do not live in freedom or justice’ .”

However, a few months after the signing of an agreement between the Military Transitional Council (MTC) and the opposition political parties coalition, represented as Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC), many Sudanese started to lose hope in seeing any serious change. The groups that signed the agreement belong to a conservative segment of society.

Bedayaa noted that, following years of political unrest, the situation is still fragile. Implementation of legal reforms depends in part on the cultural values of the law prosecutors and their personal views. Implementing the law can be delayed, neglected, or ignored in the local police stations and other legal facilities. This has to be seen against the backdrop of bureaucracy which by default can be a challenge, as well as the nature of executive entities that are trained in “masculine normativity’”

The latest amendments are fragile and do not tackle the roots of homophobic abuses. For example, life imprisonment is still allowed as a punishment for men who have sex with men. A police officer can detain someone based on “suspicion” for 24 hours (Article 67 of Sudan’s penal code). Generally, the legal procedures and the challenges that could face LGBTQI+ community are similar to what many women face on a daily basis, including harassment, abuse, and discrimination while in police control.

As the report noted: Recently the death penalty was removed from the legal code. However, criminalization of same-sex relations is still present. On top of this , few laws protect LGBTQI+ rights or safety.

Sudan was part of a statement presented to the UN in 2008 against the decriminalization of homosexuality. Yet Sudan signed the international agreement on economic, social, and cultural rights, which obliges it to ban all discrimination based on sex, religion, or sexual orientation.

Bedayaa maneuvers through a hostile environment

Editor: Bedayaa’s official website and contact phones are all down. But its executive director, Noor Sultan, gave an interview to the Web security company Cloudfare on working in a hostile environment. The interview is reproduced below with slight edits.

Bedayaa’s online platform is critical for the LGBTQI people in the region. Noor Sultan, executive director of Bedayaa, explained that “Some of the people in this community do not want or dare to be in touch with people on the ground to discuss and get involved with others. They fear that meetings in person may jeopardize their security. Digital communication could, if done in a secure way, solve this problem because it allows people to communicate from anywhere.”

Sultan continued, “There is clear a lack of resources that talk about homosexuality in Arabic. There are few resources that give a clear understanding of what homosexuality is and how a homosexual person can live and survive in countries like Egypt and Sudan. Furthermore, there are no Arabic-language resources that provide social and psychological advice and support to those who may need it or who feel affected negatively by social norms. This is the hole we try to fill with the Bedayaa Platform.”

Confronting oppression

The biggest threat to Bedayaa is tracking and censorship by the government, since the Egyptian and Sudanese governments are both very aggressive regarding SOGI (sexual orientation and gender identity) issues.

“There are many reports of incidents involving the tracking and arrests of homosexuals through online platforms,” noted Sultan. “Thankfully, we’ve never faced a problem through our website, but other platforms (social media, Facebook, online dating) have had issues. Police spies create social accounts, and when you go to meet them in person they turn out to be police and arrest you.”

Bedayaa also had difficulties with attacks on their website temporarily knocking it offline or preventing access altogether.

“Sometimes the website wasn’t there,” Sultan commented. “We’re not sure if it’s a technical problem or if it’s the government trying to stop us.”

Bedayaa gets a helping hand

Bedayaa turned to Project Galileo to try to ensure their site would be protected and kept online despite the attacks they were experiencing. Project Galileo is a program of Cloudflare the provides free cybersecurity protection for at-risk public interest groups.

“We are apart of a global LGBT movement,” Sultan related. “To exist as an organization serving or raising awareness of homosexuality or transexuality in Egypt, this is important work to do. We raise awareness and connect to international movements. It’s helpful, when you become more vocal and visible about the LGBT situation in Egypt and you get the spotlight from the international community on the arrests and violence, which further increases visibility for the LGBT community. We work to spread awareness and end this violence. Project Galileo helps us do that.”

Sex trafficking of boys contributed to Taliban victory in Afghanistan