Haiti: Violence keeps raging a year after Charlot Jeudy’s death

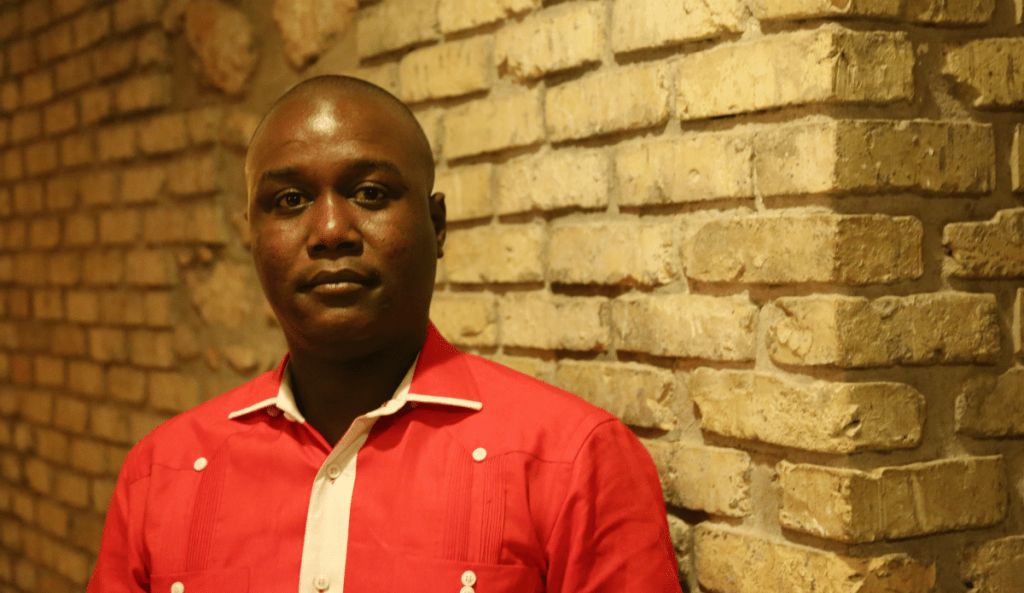

Moïse Manoël-Florisse, is an African-Caribbean online journalist keeping an eye…

INTERVIEW. Almost a year after the suspicious death of Haitian LGBT leader Charlot Jeudy, violence against the LGBT community rages on in a nation in crisis.

In a telephone interview on Oct. 15, LGBTQ rights activist Moïse Manoel posed a broad range of questions to Edmide Joseph, coordinator of Women in Action against Stigma and Sexual Discrimination (FACSDIS) in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

Since the death of Charlot Jeudy, has there been any news on the autopsy and the investigation? What has changed over the past year?

A year later, the shadow of Charlot Jeudy’s death still looms over the Haitian LGBT community.

Since Charlot’s death on Nov. 25, 2019, we are still awaiting the results of the autopsy. Without them, there will be no conclusion to the investigation, which for the time being has stalled. It has been going on for too long now, almost a year. For a year, we have kept holding the authorities to account.

If necessary, to commemorate the sad anniversary of the disappearance of Charlot, next month we will once again make our voices heard. This opacity around the conclusions of the autopsy smacks of political scandal to me.

Indeed, the families of several people who died this year long ago got the results of the autopsy of their deceased. It looks like there is an underlying homophobia in this refusal to disclose the causes of Charlot’s death.

In any case, for the Haitian LGBT community, we can say that the death of Charlot is far from having put an end to the violence. Quite the contrary. It has redoubled. For example, the former CEO of FACSDIS has been threatened on several occasions, so much so that she had to seek refuge in the Dominican Republic. For now, she still refuses to return to Haiti because she is traumatized.

Churches are often the source of messages of hatred and violence. Through a climate of fear and intimidation, it is also a political means of controlling the masses — sexual minorities as well as women. This atmosphere, instilled by preachers with the consent of a certain discredited political class, is conducive to violence against women. Too often they are raped and abused and the situation worsens. Abusers often take advantage of the ignorance of women, including lesbians, about their rights in Haitian society. We need community capacity-building actions to be implemented in this area.

For several months, there has been political paralysis in Haiti. How does the Haitian LGBT community position itself in relation to this? And how did you cope with the Covid-19 pandemic?

The LGBT community is experiencing a situation of intense stress in the midst of the Covid-19 epidemic. There is a lot of information missing on the pandemic in Haiti. The epidemiological data collected are incomplete and random. Some regions are difficult to access due to a lack of transport infrastructure. Dispensaries are unevenly distributed in a country that finds itself globally helpless in the face of this new pandemic. This situation of a population abandoned and left to itself, poorly educated, in the midst of international health chaos, constitutes a fertile ground for rumors for desperate people seeking explanations in the face of all these curses and catastrophes coming from abroad.

As soon as a disaster hits the shores of Haiti, pastors seeking to control a fragile and credulous population immediately accuse individuals who question their political and community leadership of being the perpetrators. Often LGBT people are directly targeted. Many pastors preach a corrupt form of Christian theology that focuses power of them and allows them to discredit the freest elements of society, such as homosexuals, who resist their influence.

After the January 2010 earthquake, the LGBT community was accused of causing it and all the deaths and destruction that resulted from it. Bible verses about the fire of God falling on Sodom and Gomorrah were invoked in support of this apocalyptic explanation, which also declared that the end of the world was near.

Whenever there is an uproar in Haiti, whether in politics, the economy, society, the climate or in the earth itself, the LGBT community is blacklisted. And now those attacks are raining down.

For three years, we have been in the midst of a political crisis. Nothing is working in Haiti. You cannot go out and go to work without fearing for your safety. There are regular strikes and demonstrations. Haiti’s economic situation is unstable. Public services are at a standstill. We speak of “country-lock” to designate with resignation this type of paralysis.

As LGBT activists, this gridlock frequently affects us, as we cannot do the work of awareness-raising and violence prevention outside the walls of our homes. However, the violence against lesbians knows no respite.

Recently, there has been a resurgence of violence in the region of Port-au-Prince, with one murder and one unsolved disappearance. Can you tell us about the deceased, if you knew them?

Regarding the missing young man, he is a Kouraj [Haitian LGBT rights group] activist. Since Oct. 05, we have had no news of him. The investigation has stalled.

Regarding Maïkadou, I got to know him through a common acquaintance that we had. Maïkadou was a very caring and gentle boy.

He was a makeup artist who studied cosmetology at the famous Michel Chataigne school in Haiti. It is said that Maïkadou was Haiti’s greatest makeup artist. He was also a pillar of the LGBT community in Port-au-Prince, due to his fame and professionalism.

Before his death, in his last voice note on Whatsapp, he said he felt very melancholy about the situation in the country. Like many here in Port-au-Prince, he felt compelled to secure his home to avoid an attack.

The next day, Maïkadou’s body was found lying on the ground by his housekeeper. The position of the body and the multiple injuries leave little room for doubt [that he was murdered].

In his case, as in the case of Charlot Jeudy, we are calling for a serious and successful investigation.

What is the political agenda of the Haitian LGBT community now? What are the remaining challenges in your opinion?

There is an advocacy committee in Haiti, but this year we haven’t had much time to meet.

There was a bill at the end of the first semester to allow trans people to have a national ID card that takes into account their new gender identity. It drew a lot of ink, as you would expect. Obviously, Christian religious leaders opposed it in public statements and by lobbying facing elected officials, in order to extend their hold over the population. But the law was adopted and since then it has not made waves.

Today, our main challenge is to get our voice heard by the government, so that the results of the autopsy of Charlot Jeudy’s body can speak and advance the investigation. Achieving the right to effective and fair justice is still a challenge in Haiti.

Haiti is often portrayed very negatively in the international press. For you, what are the factors of hope that you see for the future of your country?

I see the future of my country in dotted lines or in a fog. Here we live from day to day. Politicians follow one another. Things don’t change in the material life of Haitians. This impacts women negatively, alas. Above all, there is not much work in Haiti for young people. Daily life in Haiti is full of uncertainty. We leave home in the morning without ever being sure of being able to return. Everything goes through System D [getting by, fending for yourself]. Here, it is the reign of day-to-day resourcefulness. So, for some, the future lies in exile — Chile, Brazil, Dominican Republic — but it takes money and networks to accomplish that.

Others earn their living through organized crime. We have very serious insecurity issues. We are afraid to go out. We are afraid of people. We are afraid of motorcycle taxis and kidnappings. Sometimes the bandits are dressed in uniform with fake police cars. The kidnappers often ask for US $ 1 million. We wonder who benefits from this climate of fear that is taking hold in Haitian society, in Port-au-Prince, in the capital?

Ultimately, if we do not have a stable country, we LGBT people in Haiti will be unable to lead stable lives.

Related articles: