Slow or no progress in Central Africa

Colin Stewart is a 45-year journalism veteran living in Southern…

In the last two years, issues related to sexual orientation and gender identity have not seen much progress in Central Africa. These issues continue to be perceived as taboo and “contrary to African values”. In addition, many people still believe that these are issues “imported from Europe”.

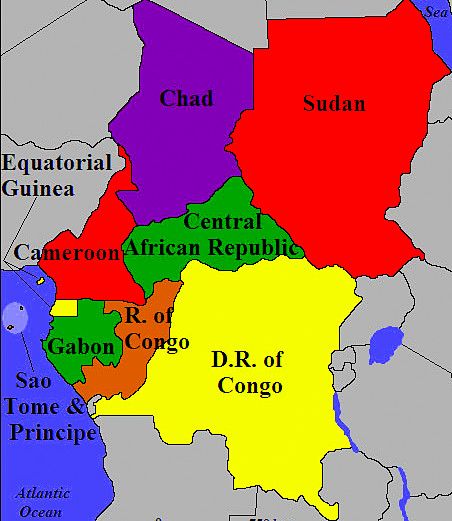

Two Central African human rights activists provide an overview of LGBT rights in five nations — Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Gabon and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This article is published here courtesy of ILGA, the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association:

An overview of some Central African countries

By Julie Makuala Di Baku and Jean Paul Enama

It is only necessary to walk the streets of several Central African countries to understand how difficult it is to be seen as a couple with a person of the same sex. In the region, while in some countries there are explicit laws that criminalize same-sex sexual acts, in others there is a legal vacuum on the matter.

Although Cameroon revised its criminal code in 2016, the provisions that penalizes same-sex relationships were unfortunately kept intact. [The label for tat section was simply changed from 347bis to 347-1, with no change in the text.] In the international arena, Cameroon has rejected all recommendations on issues of sexual orientation and gender identity. Even so, there is some political will to eradicate HIV from key population groups and the National Health Plan 2018-2022 identifies men who have sex with men (MSM) and trans women as a vulnerable population.

In the Central African Republic, although same-sex sexual relations between consenting adults are not explicitly criminalized, article 85 of the criminal code criminalizes “acts against nature committed in public”, defining them as “attacks on public morals” and imposing harsher penalties compared to other attacks on morals. Alternatives Centrafrique, a local LGBT organization, has documented cases of arbitrary arrests based on (false) allegations of same-sex sexual intercourse. In this line, in its 3rd cycle of the UPR, the Central African Republic received two recommendations (prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity and improve the situation of sexual minorities). The National HIV Plan 2016-2020 identifies MSM as key populations, so the actions of the Global Fund project focus on them.

While there is no law in Gabon criminalizing consensual same-sex relations between consenting adults, the human rights situation of LGBT people remains extremely worrying, with arrests for “moral attacks” based only on the form of dressing “translating sexual orientation”. Gabon had its first recommendation on SOGIEC [sexual orientation / gender identity / gender expression / intersex / sex characteristics] in the third cycle of the UPR [the Universal Periodic Review of nations’ human rights records] in 2017, which focused on access to medical care for LGBT people. In fact, the National Health Plan does not recognize gay and bisexual men as a key population.

Before 2017, the legal situation was not particularly clear in Chad: Article 272 of the Criminal Code condemned those who committed “acts against nature” with persons under 21 years of age. A bill to criminalize same-sex relations with up to 20 years in prison was debated in Parliament in 2016 but failed to pass. However, the revision of the Criminal Code that entered into force in 2017 incorporated the criminalization of “same-sex sexual relations”, making Chad the latest State to criminalize same-sex consensual relationships and, therefore, a worrying example of legal regression in the region. Furthermore, the National Health and HIV Plan does not identify key populations and there is no record on any LGBT organization operating in the country.

Of particular gravity is the situation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where LGBT people continue to be victims of human rights violations and face increasing discrimination and stigmatization. While same-sex sexual relations between consenting adults are not expressly criminalized, Article 176 of the Criminal Code— which criminalizes activities against public decency—is used in practice as the legal basis to criminalize LGBT persons.

There are numerous documented instances of arbitrary arrests and blackmail perpetrated by the police in which this provision is used to persecute and repress public displays of affection, non-normative gender expressions, among others.

In this regard, the Human Rights Committee expressed its concern and recommended that the State ensure that no person is prosecuted under Article 176 of the Penal Code because of their sexual orientation or gender identity, as well as enact anti-discrimination legislation that expressly includes sexual orientation and gender identity. Among the few positive aspects, it should be mentioned that the Democratic Republic of the Congo has a law to protect people living with HIV/AIDS. Articles 3 and 4 of this law prohibit acts of stigmatization and discrimination against any person living with the virus.

In addition, article 2 contains a definition of “vulnerable groups”, which includes sex workers and “homosexuals”. This law is today the only legal text in force that can be used to offer protection to LGBT people, although mainly with respect to men who have sex with men. Unfortunately, this means that lesbians and trans people must use the label of one of the groups identified as “vulnerable groups” to have access to care.

About the authors: Julie Makuala Di Baku is the founder and executive director of Oasis, a Congolese association for LBT women. Jean Paul Enama is the executive director of Humanity First Cameroon.