Akwaaba! (Welcome!), says Ghana — but not if you’re gay

Colin Stewart is a 45-year journalism veteran living in Southern…

By Yaw Amanfoh

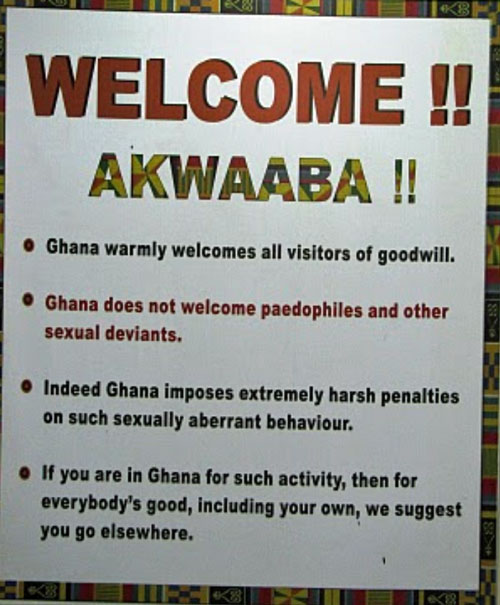

“Wecome!! Akwaaba!!” says the sign at Accra International Airport. In the photo, taken in 2010, the mixed message is framed by a traditional kente print.

It starts off with a warm welcome, then quickly reverts to the hatred of “sexual deviants.”

In the Ghanaian Criminal Code, Article 104 of Chapter 6 defines this “sexually aberrant behavior” as “unnatural carnal knowledge.” This means that Ghana criminalizes same-sex intimacy between men. If men of sixteen years or older are caught having consensual sex, they can be sent to prison for that misdemeanor for up to three years. The law makes no distinction between homosexuality and bestiality. Same-gender love between women isn’t criminalized under the law but is still highly discriminated against.

So, in the same breath, as Ghanaians extend their “akwaaba,” they also condemn and reject everyone with a queer identity, including Africans from the diaspora.

“Seeing this sign when going through customs stands out in my mind as one of my most vivid experiences in Ghana” says Robert Reid Drake, a white, queer-identified graduate from the University of North Carolina at Asheville.

Every summer, students from UNC-Asheville spend a month in Ghana to take a few classes and to explore the land of the Gold Coast. Reid says:

“I was well aware of Ghana’s anti-LGBT laws before arriving, but thinking about it in a classroom is something entirely different from being in a room, about to go on a month-long trip, and being directly confronted by it.

“It felt like ‘Okay…how are you going to process this, Reid? Is this something for me to feel personally outraged, saddened, attacked by? Or is this something that I need to wade through with the patience of an outsider?’”

Despite Reid’s inner conflicts and skepticism before and during the trip, Reid had a good time in Ghana, without raising the issue of how Ghana treats sexual minorities:

“I felt welcomed in Ghana. But I think that a lot of that was due to the fact that unless I intentionally inserted queerness, my own or otherwise, into the conversation, it went unconsidered and undiscussed.”

As a visitor from the United States, Reid knew that whiteness would be a dominant identity in Ghana. But Reid also thought that hidden queerness could be used to try “to remain in the moment and have genuine experiences.”

As a queer person in the United States, Reid’s aesthetic of “cut-off short-shorts and glitter makeup” is noticeable but not hazardous in the tolerant American town of Asheville, North Carolina. Reid felt the need to shelter that queer identity while in Ghana, where “queerness could [prohibit] access to so much” or potentially could result in harm.

This may simply be what’s required of a person of LGBT+ identity visiting Ghana, or any country with anti-queer practices. In order for visiting queer Africans of the diaspora and varied ethnicities to be socially accepted in Ghana, they simply must “[go] back in the closet,” an experience that “holds different meaning for different people,” Reid suggests.

“It was kind of good to fall back inside it,” Reid says. The experience was actually enriching, Reid found, allowing critical analysis of the identities of race, gender and sexuality in the U.S. versus in Ghana. For other people, unfortunately, it could mean a reeling back into depression or suicidal thoughts.

“I acted as straight as possible because I didn’t want attention drawn to me during my trip,” says Titi Adeniyi, a current student at UNC-Asheville who also went on the Ghana trip. “I felt it was of utmost importance to be as straight as possible and be vague of my sexual history as a female.”

Titi, a queer-identified Nigerian, acknowledges that the homophobia of Ghanaian society led to the decision to keep quiet about that queer identity.

Of course, homophobia isn’t a problem only for visiting queer individuals. “[My employer learned] information [about my] orientation and sacked me,” says Eddie, a lesbian living in Ghana who wants to remain anonymous for safety’s sake.

Eddie is no stranger to the process of switching from her queer persona to a “straight” appearance. Around her queer friends and in comfortable spaces, Eddie doesn’t hide anything about herself. But when she is in the public eye, she “doesn’t even feel [safe]” and is “always in the closet.”

“I might be at risk if I show off my sexuality since [it’s] not accepted in my country,” she says.

That lack of acceptance is evident in the airport’s hate-filled message and in a Pew Research finding that 96% of Ghanaian citizens disapprove of homosexuality. Ghana, along with many other African countries, has a long way to go in recognizing human rights for all citizens and eradicating anti-queer practices.

Yaw Amanfoh is a Ghanaian-American, queer-identifying, gay man who recently graduated from the University of North Carolina at Asheville with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics.

Related articles

- Ghana arrests reputed leader of violent anti-gay gang (Sept. 18, 2015, 76crimes.com)

- Two victories over Ghana’s violent homophobe (Aug. 17, 2015, 76crimes.com)

- Warning: Violent homophobe active in Ghana (Aug. 15, 2015, 76crimes.com)

- Don’t jail gays, says son of Ghana independence leader (76crimes.com)

- Ghana uproar: 53 students ejected for homosexuality? (76crimes.com)

-

Threat to lynch Ghana gays; Uganda deportee dies (76crimes.com)

- Tough life for gays in Ghana (76crimes.com)

- Ghana’s HIV prevalence for 2013 declines (GhanaWeb)

- Ghana needs policy to protect gay rights – CDD (Pulse)

- Ghana: Draft HIV Bill Before Parliament (AllAfrica.com)