Uganda's anti-gay bill makes AIDS harder to fight

Colin Stewart is a 45-year journalism veteran living in Southern…

The work of AIDS fighters in Uganda has grown more difficult because of the passage of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill, even though it has not been signed into law.

Many LGBT people are again afraid to go to health clinics, even the ones that in recent years had gradually been persuaded to serve them, because sexual minorities are increasingly treated as criminals.

“We are trying to work underground, but now the challenge is that we have so much more work to do than before,” said Frank Kamya, a leader of the anti-AIDS group Come Out Post-Test Club, which serves dozens of transgender women sex workers in Kampala. “All our members are relying on us now, not like before when they could access some health facilities themselves. But now they are living in fear, panic and tension.”

“We now have to provide them services ourselves,” Kamya said. “Now the challenge is that all that needs funds, which we don’t have at all.”

LGBT-friendly anti-AIDS organizations, such as Spectrum Uganda, the Good Samaritan Consortium and the Post-Test Club, fear that the Anti-Homosexuality Bill (AHB) has reversed their recent progress in convincing some Ugandan health professionals to treat LGBT patients.

“Many things changed after the passage of the AHB,” said one Ugandan transgender HIV activist. That includes reduced access to antiretroviral (ARV) medication for HIV-positive patients. “Many of us are positive and we can’t now access ARVs because of the bill. We all fear to go and pick up our meds because of the AHB.”

The clinics are also afraid to serve LGBTI patients because of the bill, the activist said. “Doctors said they have no meds for anal gonorrhea. … I knew it’s because they knew I was gay that they refused.”

The O-blog-dee advocacy blog describes the situation thus:

The severe impact of this bill has started eroding way the efforts to combat HIV-AIDS and STDS among sexual minorities in Uganda. Health service providers are steadily pulling out in this struggle for fear of their lives and jobs.

The Bill, though yet to see finality into law, is already driving people underground, and will continue to disrupt the collection and dissemination of accurate and imperative information.Threats, hateful speeches and discrimination from religious leaders, politicians and even biased media are increasing and resulting into insecurity to peer educators, staff and LGBTI community, which is hampering health service delivery. When this law is enacted, it is anticipated, according to Spectrum, that it will get even worse.

The nation’s LGBT communities — excluded from most health clinics and with little access to information about HIV/AIDS — suffer from higher HIV infection rates than the national average. The national HIV rate is about 7.5 percent, but the rate for men who have sex with men (MSM) is estimated at about 13 percent.

Before the AHB was passed, signs of progress included:

- Uganda’s new strategic plan for the fight against HIV/AIDS mentions MSM and sex workers among the most-at-risk groups needing attention.

- The Ministry of Health is conducting a survey of the unmet health needs of Uganda’s most-at-risk populations. “We are happy the Ministry of Health is committed to establishing clinics for MSM and sex workers in Kampala,” said Moses Kimbugwe, an activist with Spectrum Uganda, as reported by Inter Press Service.

-

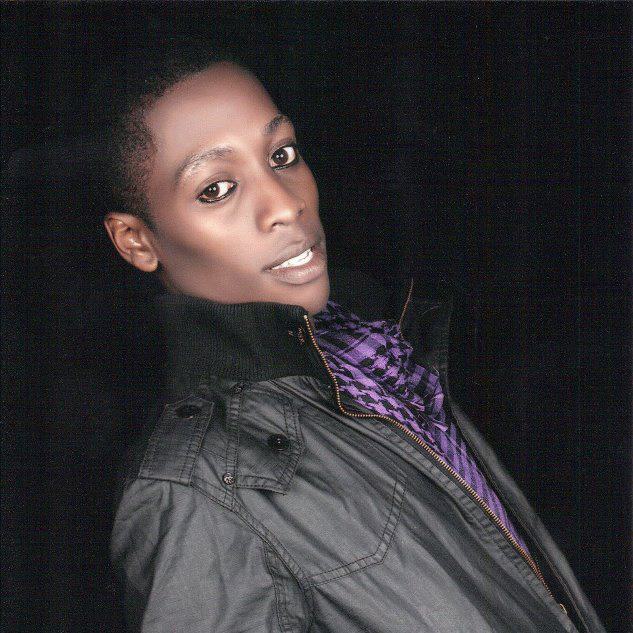

Maxensia Nakibuuka Last month, Uganda’s Roman Catholic archbishop, Cyprian Kizito Lwanga, named HIV-positive lay leader Maxensia Nakibuuka to coordinate the church’s AIDS programs in Uganda. She founded and runs the Lungujja Community Health Caring Organisation, which treats both gay and straight patients. “This is a window opened to us to ensure quality service delivery to all, especially the hard-to-reach and most-at-risk communities in Uganda, irrespective of their sexual orientation,” Nakibuuka said.

Shortly before the AHB passed on Dec. 20, Inter Press Service published an upbeat article about progress in the struggle to improve health care for LGBT Ugandans. It began:

KAMPALA, Dec 16 2013 (IPS) – At an unremarkable office on Bukoto Street in the Ugandan capital, Kampala, health workers and civil society activists attend a regular meeting to offer information and advice on living with HIV and AIDS. What is unusual is that these information sessions cater to a group of around 50 transgender women.

The “Come Out Post-Test Club”, as the group calls itself, was established early this year as a safe space and advocacy group for trans women sex workers living with HIV. The club’s executive secretary, Bad Black, says it is helping to fill a desperately needed gap in support services.

“It is one step in the right direction,” says Black. “We hold online discussions. We also have regular physical meetings in a safe space. We are about 50 members, as of June 2013, although the numbers are growing.”

According to Black, many trans women have died in Uganda because of discrimination in the public health service. “We have lost seven of our colleagues this year alone,” she recounts. “The biggest problem was negligence by the doctors. They never wanted to treat us because of our sexual orientation. We thought many more of us would die if we remained in hiding.”

The turning point for the group was in April this year when a colleague, Abby Mukasa Love, died.

“Abby wouldn’t have died if the nurses and doctors had not stigmatised her,” says Black. “They wrote the word ‘gay’ on her file. We decided to come out and form a support group and 20 of us began holding meetings every Sunday. We would invite some people to talk to us about treatment and prevention. It was not easy for many of us to come out.”

The club’s interaction with health workers at the Bukoto Street office has brought about some changes. According to Black, some health workers are opening up to offer better treatment and support to members of sexual minorities.

“To us that is a milestone, because very few would even associate with us once the Anti-homosexuality Bill was tabled in Parliament in 2009,” Black adds.

Now that progress is again under threat. LGBT-friendly anti-AIDS groups are seeking funds to bolster both their security and their ability to serve LGBT patients who are again cut off from traditional health care in Uganda.

Related articles

- Uganda parliament passes former ‘Kill the Gays’ bill (76crimes.com)

- Ugandan anti-gay bill — a self-contradictory mess (76crimes.com)

- VIDEO: Uganda Parliament passes draconian anti-gay bill (YouTube)

- The Text of Uganda Anti-Homosexuality Bill as Passed (O-blog-dee)

- Museveni to study anti-gay Bill before assenting (New Vision)

- Ugandan activists’ advice on threats to cut aid (76crimes.com)

- Uganda’s gays fear mounting violence (edition.cnn.com)

- Activist: Most Ugandans support anti-gay bill but the government is worried about losing aid (pinknews.co.uk)

- Dispute over LGBTI clinics in Uganda (76crimes.com)

- Sexual Minorities Fight for Health Services In Uganda (ipsnews.net)

- Ugandan LGBT Activists: ‘We Have to Stay and Fight’ (advocate.com)

- US condemns Uganda’s anti-homosexuality Bill (nation.co.ke)

Reblogged this on Embakasi Reloaded.